Gagarin was one who they called a “regular guy from the masses”: his father was a shepherd, his mother – the head of a pig farm. When he was a child, he spent one and a half years under German occupation. After school, he went to study to be a foundry worker and, at the same time, joined an air club. When he was drafted into the army, he was sent to the air force. This practically kickstarted his flying career. Having accumulated 265 hours of flight time, he received the ‘Military pilot 3rd class’ qualification and was promoted to the rank of senior lieutenant.

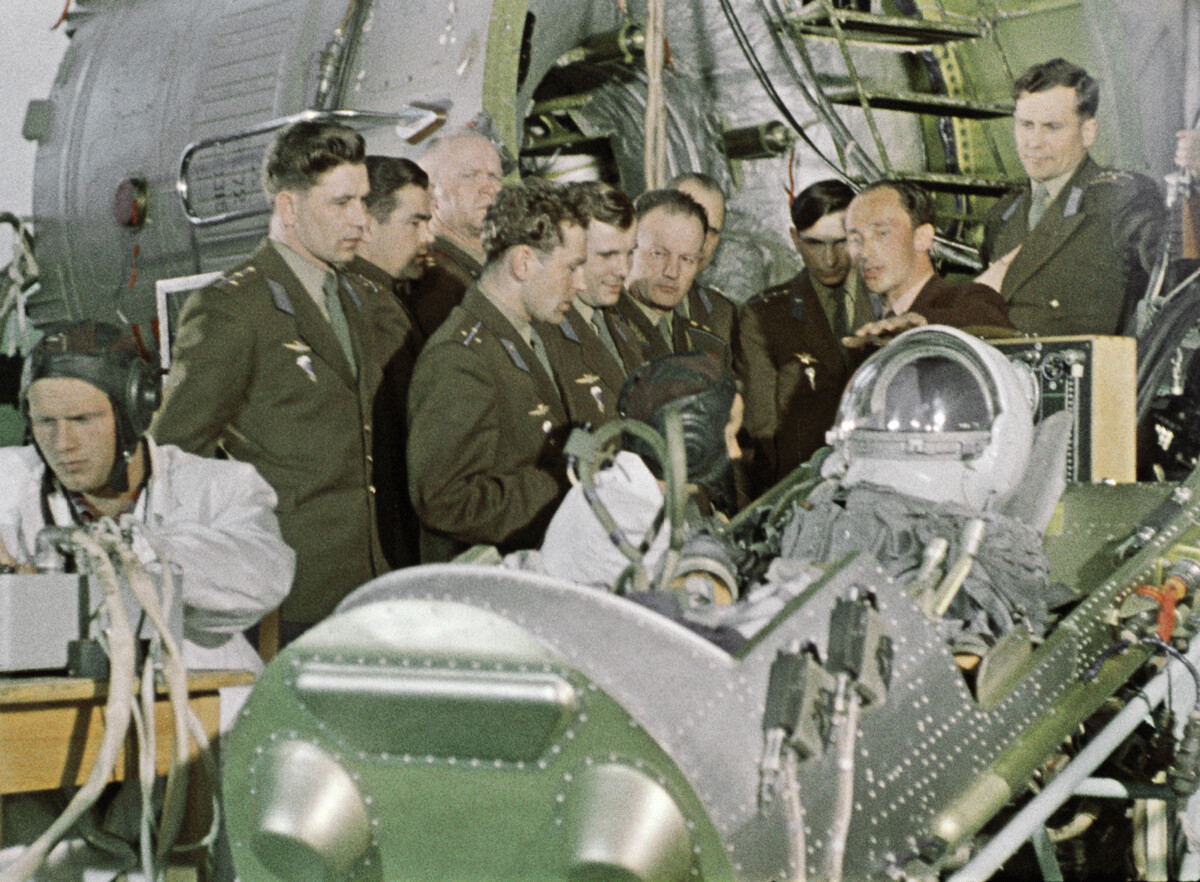

Before his flight, dummies were sent to orbit four times and one of them burned down. This information was kept in strict confidence, but everyone knew that there was a real chance that Gagarin could not return back from space.

Especially since, three days before the flight, Sergei Korolev, the head of the space program, decided to show cosmonauts how the R-9A ballistic missile takes off. But, at 8 am, the missile exploded at the launch site right before the cosmonauts’ eyes. Korolev quickly assured Gagarin that his rocket, the R-7, is much more reliable.

However, Gagarin still wrote a farewell letter to his wife.

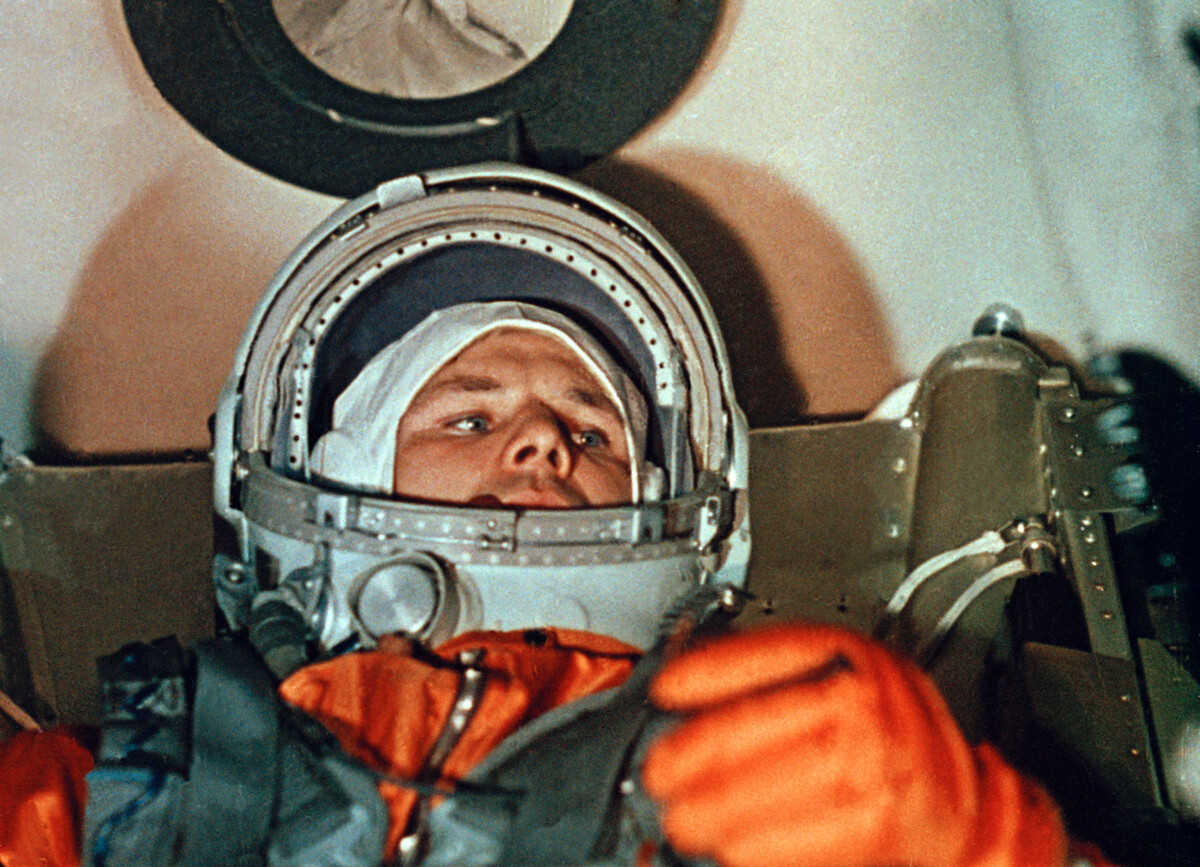

At that time, no one knew yet how a spaceship that passes through the layers of the atmosphere looks from the inside. So, when Gagarin saw flames on the outer surface of the Vostok-1 space capsule, he panicked and contacted the flight control center: “I’m on fire, goodbye, comrades!” Later on, this little episode was hushed up.

Landing in a space capsule during these years was still technically impossible: Gagarin had to eject out of it with a parachute. However, when he ejected according to plan, an air supply valve in his hermetic suit didn’t open right away. The first man in space, who conducted the most dangerous journey, almost died at the last stage of his mission.

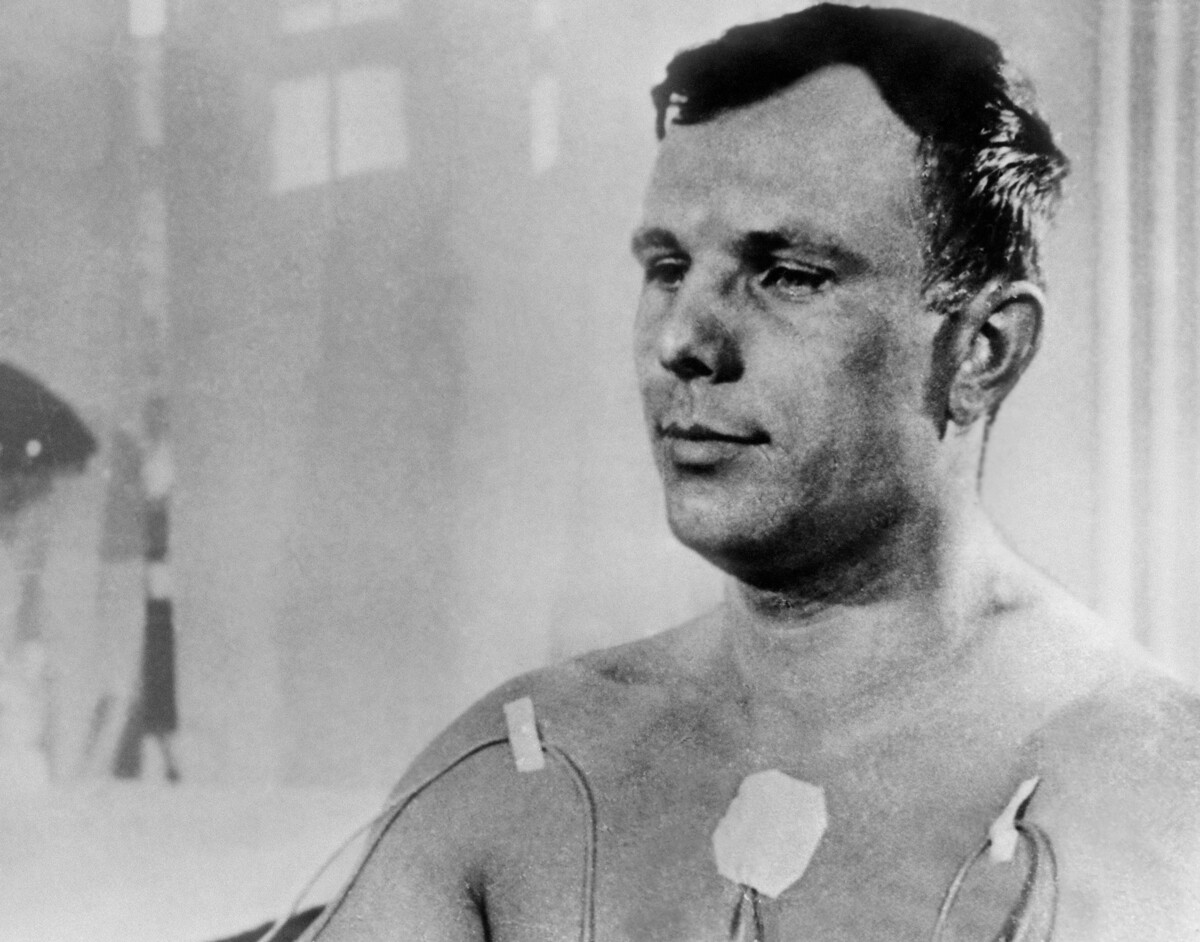

He was athletically built, well-coordinated, aced all the tests and, yet, he didn’t have any winning talents over other candidates for the first space flight. There were other factors in Gagarin’s favor – he was photogenic, he had a euphonic name and a disarming smile. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev knew that the first cosmonaut would automatically become a public figure, the “face of the country”. He realized that this face should be attractive.

To minimize the risk associated with piloting a spaceship, it was decided to conduct the flight in a fully automated mode. The cosmonaut could only take control if automatic systems failed. But it never came to that.

For a long while, this information was kept secret, but now we know: the Soviets evaluated the first flight of a man to space as worth 15,000 rubles – at the time, equal to 187 average monthly salaries in the USSR. But, Gagarin didn’t receive just money. They gave him a fully furnished four-room apartment, a luxury car, a house for his parents; they supplied him with absolutely everything he needed – from coats and shirts to an electric shaver. We talked in detail about how it was arranged and how much do cosmonauts earn nowadays here.

On April 12, 1961, the entire USSR pushed all its other matters aside: the workday was “ruined”, it turned into a celebration of a national scale. Yuri Gagarin, previously unknown, in mere hours became a star. Watch here how he was welcomed on the streets of the USSR.

Gagarin was immediately sent on a world tour across 29 countries. He had lunch with the queen of the UK, got soaked in a tropical rain in Cuba with Fidel Castro and went to a meeting with Italian actress Gina Lollobrigida.

“I liked everything about her: her character, her short stature, her brown eyes full of light, her braids and her small, slightly dusted with freckles, nose,” Yuri Gagarin said about his wife Valentina. Together, they lived for 11 happy years. Even when global fame and the love of thousands of women crashed down on Gagarin, he remained faithful to that modest girl “in a simple blue dress”. After the death of her husband, Valentina never remarried and never gave an interview. Read about what happened to her here.

Because of endless tours around the world, Gagarin’s health deteriorated greatly and he gained weight. That bothered him: the cosmonaut worried that the high command didn’t have any plans for him anymore. He returned to training in 1963, but, as he feared, was not sent to space again.

As the head of cosmonaut training, Nikolai Kamanin wrote in his book ‘Hidden Cosmos’: “Gagarin hopes that someday he’ll conduct new space flights. It’s unlikely that will ever happen. Gagarin is too precious to humanity to risk his life for a regular space flight.”

Due to the inability to conduct another space flight, the cosmonaut suffered. Depression engulfed him. Alcohol addiction soon accompanied it: everyone, from relatives to ministers and marshals, wanted to drink with Gagarin – to friendship, to love, to space, and a thousand more reasons.

More and more rumors spread about Gagarin’s drunken conduct. The most famous story of his alcoholism happened at the Black Sea resort of Foros. Gagarin jumped off the balcony of his hotel, fractured a facial bone and spent a month in a hospital.

Gagarin died in the cabin of a MiG-15 aircraft in the Spring of 1968, during a routine training session. The aircraft entered a spin and crashed, after Gagarin had declared the end of his flight assignment and his return to base with a calm voice.

The investigation resulted in 29 tomes of top-secret documents, but no conclusion about the circumstances of his death, even the briefest one, was published. Only in 2011, based on these documents, a sudden maneuver and a collision with a high-altitude balloon were named as possible reasons for this catastrophe. By the way, Gagarin was not alone in the aircraft. Read more about who the second man was who died here.

By the end of the 1960s, the government had already come up with a way to avoid “the Christian style” burial: many famous people were now cremated.

And that’s what they did with Gagarin. The urn with his ashes was interred into the wall of the Moscow Kremlin, where, by that time, there was already a whole necropolis of famous communists, military people and statesmen.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox