The day of April 8, 1974, almost ended in a tragedy of epic proportions. Builders of the Leningrad Metro were drilling a routine exploratory borehole when, suddenly, water gushed out. Soon, it broke through the wall into an existing tunnel in which a train carrying passengers was passing. The tunnel was fast filling with water and sand. It was 4:30 pm.

At the time, everyone was rescued, albeit with great difficulty. But, as it turned out, this was just a foretaste of bigger problems ahead.

The April incident occurred between the stations of Lesnaya and Ploshchad Muzhestva. As became clear soon afterwards, the accident in the ‘washout’ (as the tunnel is now known in St. Petersburg) happened because of time pressures. The opening of the new metro stations was planned to coincide with a particular date – the 25th Congress of the CPSU (Communist Party of the Soviet Union) in 1976. But, the engineers knew that this wouldn't be easy: The vicinity of Ploshchad Muzhestva was notorious for a large number of seams of so-called running sand – fissures in the earth's crust filled with water and sand.

In order to build a tunnel through this part, it was necessary to either go round the running sand, go under it or freeze it and drill right through it. The builders chose the last option. To finish on time, they decided to take the tunnel along a direct route right through the ancient bed of the River Neva, the so-called ‘Kovensky Razmyv’.

Obviously, the builders were aware of the dangers of this method. Concrete emergency gates, each three meters thick, were supposed to protect the other metro stations. But, at the critical moment, they didn't help. The running sand burst out with such force that the gates didn't have time to be activated. In just a few hours, a cocktail of water, sand and ice filled more than 45,000 cubic meters of the tunnel (the equivalent to 18 Olympic-sized swimming pools!).

Following this subterranean leak into the tunnels during construction, cavities formed in the surrounding soil. Without support, the ground simply started to collapse, dragging down everything that was on the surface – i.e. the streets of St. Petersburg – with it.

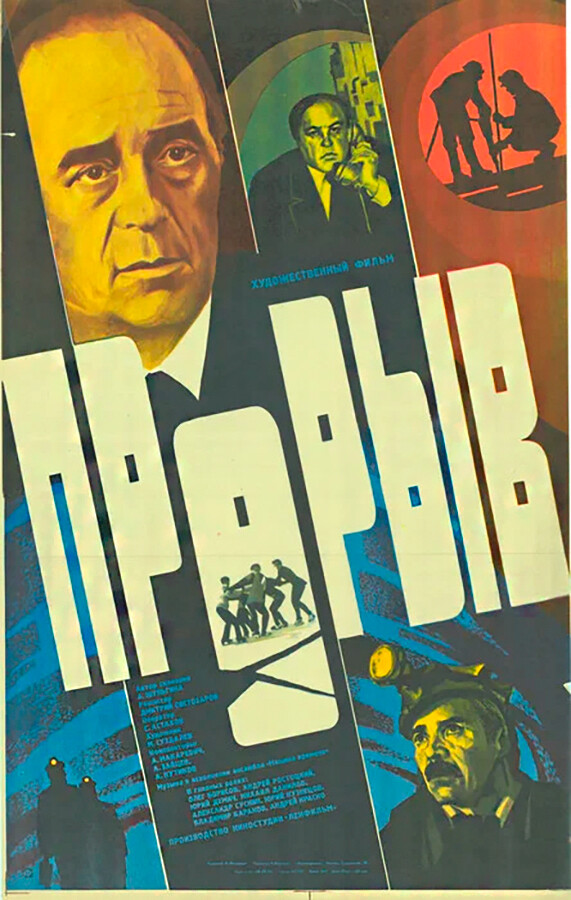

Because of ground settlement, a sinkhole 400 by 200 meters in area and three meters deep formed in the midst of the city's streets. Many streets surrounding the location of the washout were affected: On Politekhnicheskaya Street, the asphalt was left sticking up in the air and tramlines were severed, the administrative building of the Krasny Oktyabr (Red October) factory was destroyed and several other buildings in the vicinity began to tilt dangerously. Huge buildings in the very center of the city were at risk of sinking into the ground. A disaster movie titled ‘Proryv’ (‘Breakthrough’) about these events was even made in 1986.

‘Proryv’

dir. Dmitry Svetozarov, 1986/LenfilmAfter the emergency, Metrostroi, the subway construction company, started pondering how to remedy the whole situation. In order to prevent further damage occurring on the surface, the cavities in the ground were dealt with using the simple expedient of pumping mains water into them.

But, the idea of continuing to build in the same spot was not abandoned. There were two options: to construct a new tunnel going in the same direction, but higher or lower than the underground watercourse, in order to eliminate the risk of flooding; or to bypass it altogether. In the latter case, a whole additional station would need to be built.

In the end, the first option was chosen. The new tunnel began to be excavated directly above the old stretch. To prevent another mishap, the ground in this location was not frozen with standard cryogenic equipment, as on the first occasion, but using liquid nitrogen. The latter happened to be a fairly rare strategic material at the time and had to be brought in from all over the Soviet Union – in all, more than 8,000 tons of the liquefied gas were used. After the ground around the tunnel was frozen, a shield was built around the tunnel to provide additional protection for the walls of this section from a washout.

The stations were reopened in 1975. In the first few years, the tunnel was closely observed, in order to make sure any abnormality was immediately spotted: the trains and the tunnel walls were bedecked with sensors and trains passed through these sections of tunnel at low speed. But, by 1984, the builders had convinced themselves that the danger had passed and lifted all restrictions on the tunnel's operation.

The rupture sustained in 1974 made itself felt again in the early 1990s: water and sand were discovered on the ill-fated stretch of tunnel again. It turned out that the waterproofing had stopped coping.

Passengers noticed from their carriages that trains were going through muddy water. There was so much of it that the underground pumps couldn't cope with the incoming flow. In order to deal in some way with the new emergency, the metro builders initially decided to close the station on weekends and then on weekday evenings. But, again, this approach did nothing to help solve the problem – the water kept on coming.

Furthermore, the engineers had been wrong to build the new tunnel above the old one – the lower one was subject to additional stress when trains passed along the upper one. As a result, the new tunnel – and all its waterproofing and shielding structures – simply started to sink into the old one.

In 1995, the tunnel was closed again and the residential districts in the north of St. Petersburg were cut off from the rest of the city.

It was then decided to build a third tunnel at a distance of 200 meters from the old one and 20 meters above it. Trains started running along it in 2004. To date, no signs of further flooding have been detected.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox