Maria was born in St. Petersburg in 1832. Everyone around noted that the girl was a spitting image of her father. Even the poet himself had very controversial feelings about it, because, as he himself admitted, the “blackamoor ugliness” of his look (Pushkin’s ancestors on his mother’s side were Ethiopian) was not to the poet’s liking. And yet, we know that he loved his daughter very much.

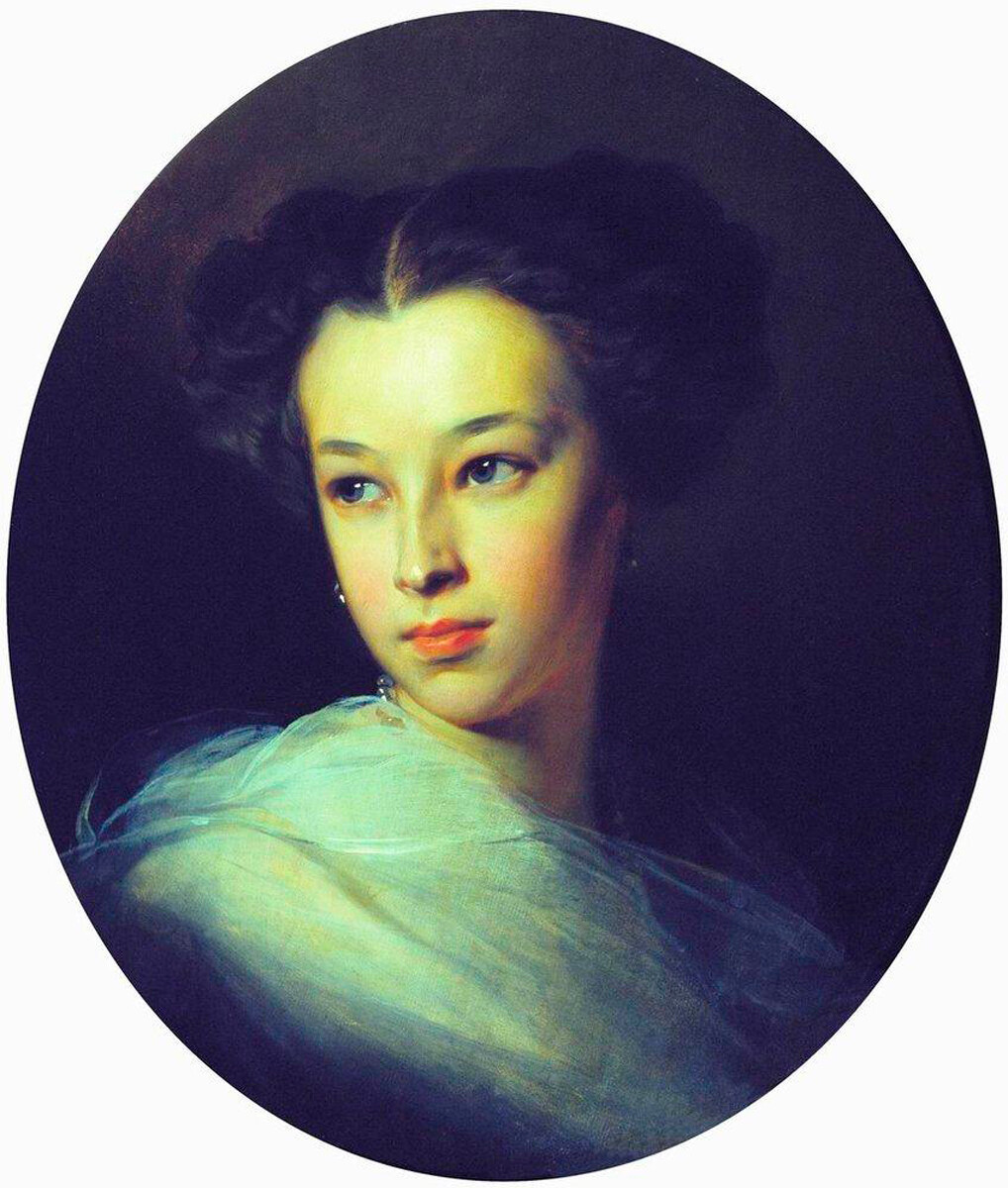

Maria Gartung

All-Russian Museum of A.S. Pushkin, St. PetersburgShe was the only child of the poet who remembered the death of Pushkin in a fateful duel well; at the time of his death, she was five. Her brothers and a sister, on the other hand, were too young to remember anything. Maria was proud of her father and considered him a model example of masculinity and talent. She cherished his memory and attended all events dedicated to the poet.

After the death of their father, the Pushkin family lived in poverty. Despite the fact that the poet was a nobleman and famous during his life, he left behind colossal debts: not just card debts, but also bills for the services of tailors, shopkeepers, bakers and so on. The family led an aristocratic way of life, which they couldn’t afford. After Pushkin’s death, his debts were covered by the emperor, but the family still lacked money. For seven whole years, Natalia Goncharova and her four children lived with her mother and brother at the Polotnyany Zavod estate. She led an increasingly reclusive life, but she also never left her kids without attention. As a result, Maria was fluent in French and German, played the piano brilliantly and knew how to draw.

Maria Gartung

The older Maria grew, the more delicate looks she acquired. In the end, she gained the reputation of an enviable beauty in noble circles and became a lady-in-waiting of the spouse of Alexander II. Even writer Leo Tolstoy was so captivated by her grace that Maria became the prototype of Anna Karenina from the novel of the same name.

Maria married at 28 – she agreed to the proposal of Major General Leonid Gartung. He was the superintendent of the Imperial stud farm in Tula and, in Moscow, belonged to a famous noble family and had great career prospects. They were truly happy in marriage. The spouses constantly arranged luxurious “tea balls” at their house. However, the family idyll was unexpectedly cut short: In 1877, Leonid was wrongly accused of embezzlement, after which he committed suicide right in the court room. And, although later, the real perpetrator was found and Leonid was acquitted posthumously, Maria was inconsolable. “Dying, he forgave his enemies, but I, I don’t forgive them,” she wrote in one of her letters. They had spent 17 years together.

With the death of her husband, Maria was left without means of subsistence. She managed to persuade Emperor Alexander II to lend her a modest material assistance – she reminded him of the letter of Nicholas I to Pushkin, in which he promised to take care of his family. After that, Maria was assigned a 200 ruble pension. With it, she managed to settle down in Moscow, but even this money couldn’t elevate her out of poverty. After the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Maria’s relatives ended up in different parts of the country and no one could help her. In 1918, she asked for a pension from the new government that she could live off of and she was assigned 1,000 rubles per month.

However, Maria Gartung never got to see this money – in 1919, she died from starvation in complete solitude in a small room. It happened before the bureaucratic machine could settle the matter and pay her the money.

Alexander Pushkin and Natalia Goncharova had three more children, apart from Maria – Natalia, Alexander and Grigory. None of them could outlive their older sister.

Natalia spent almost half of her life abroad in Hungary trying to break her unhappy marriage with Mikhail Dubelt, whom she married at 17. Hoping to earn a bit of money to live off, she, along with writer Ivan Turgenev, tried to publish Pushkin’s letters; however, both society and her family in the form of her two brothers Alexander and Grigory did not support this initiative – many considered such a thing “a vulgarity” and an attack on the authority of the great poet. The thing is that the publication of the writer’s letters, according to the public, was premature and looked like a demonstration of “dirty laundry”.

Natalia Alexandrovna

Public DomainAfter her divorce, Natalia married German prince Nikolaus of Nassau, with whom she lived until the end of her life. She died in 1913 from embolism – an illness where foreign bodies are found in the blood, for example bacteria that block blood vessels. However, Natalia did manage to give birth to six children over the course of her life – three with each husband.

Alexander Alexandrovich

Public DomainPushkin’s elder son dedicated his life to the military and managed to earn the rank of general of cavalry. His first wife was Sofya Lanskaya – she was an orphan and was raised in the noble family of Lansky. With her, he had as many as 11 children. In his second marriage to Maria Pavlova, Alexander had two more children. He died in 1914 in the village of Maloe Ostankino near Moscow at the age of 81.

Alexander Alexandrovich

Public DomainThe younger son Grigory, as his older brother, first made a career in the military, but, in the end, became a magistrate. Following the example of his older sister Maria, he cherished the memory of his father and even set up an office like his father’s in the family estate in Mikhailovskoe. In some details, this room was reminiscent of ‘Eugene Onegin’s office’ and was, in essence, one of the first memorial places that immortalized the memory of Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin. Later, Grigory gifted the entire library of his father to the Rumyantsev Museum.

Grigory Alexandrovich

Rostov-on-Don Regional Museum of Fine ArtsHe died on the estate of his wife Varvara Moshkova in Markucie near Vilna (modern Vilnius) in 1905. In marriage, Grigory and Varvara had four children.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox