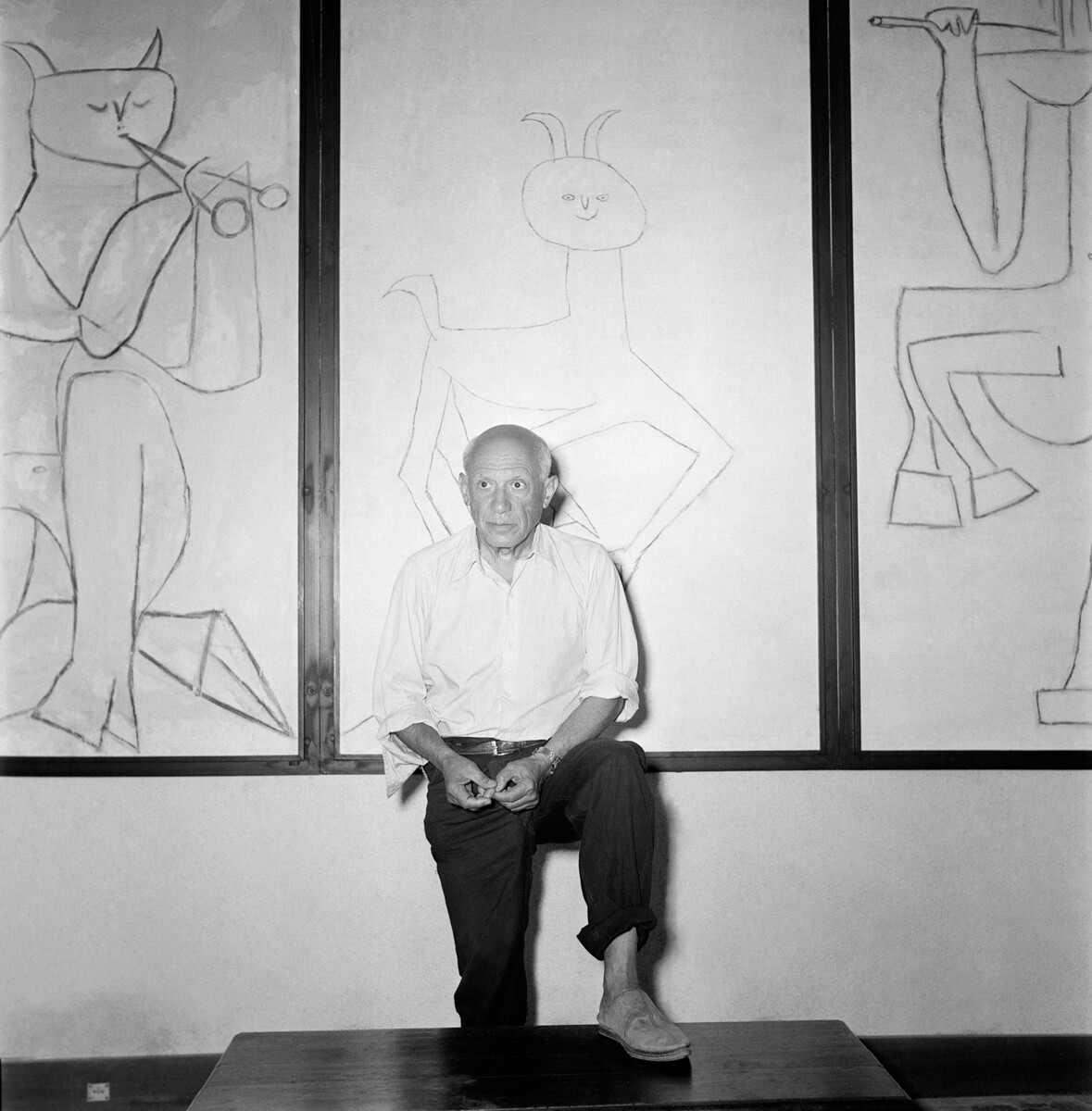

Picasso joined the French Communist Party in 1944 when the Nazi occupation of France came to an end. And, although his membership didn't oblige him to attend all party meetings, the artist was often present at them and gave party leaders his pictures as presents.

Exhibition of Picasso Ceramics at Antibes Museum, 1948

Reporters Associes/Gamma Features via Getty ImagesAs it happened, the party didn't approve of Picasso's artistic style, which was such a far cry from realism, but it willingly accepted his donations in the form of paintings – and would proceed to sell them.

In 1949, the French General Confederation of Labor approached the artist with a request to make a drawing as a present to Stalin on his 70th birthday. Picasso did the job, but confined himself to allegory: On a piece of paper, he drew a hand with a raised wine glass and wrote an inscription saying: "Staline à ta santé!" ("To your health, Stalin!").

His fellow comrades in the party saw such familiarity as outrageous and condemned the drawing. But, that turned out to be nothing compared with the storm of controversy unleashed by his next drawing of the "great leader of the peoples"…

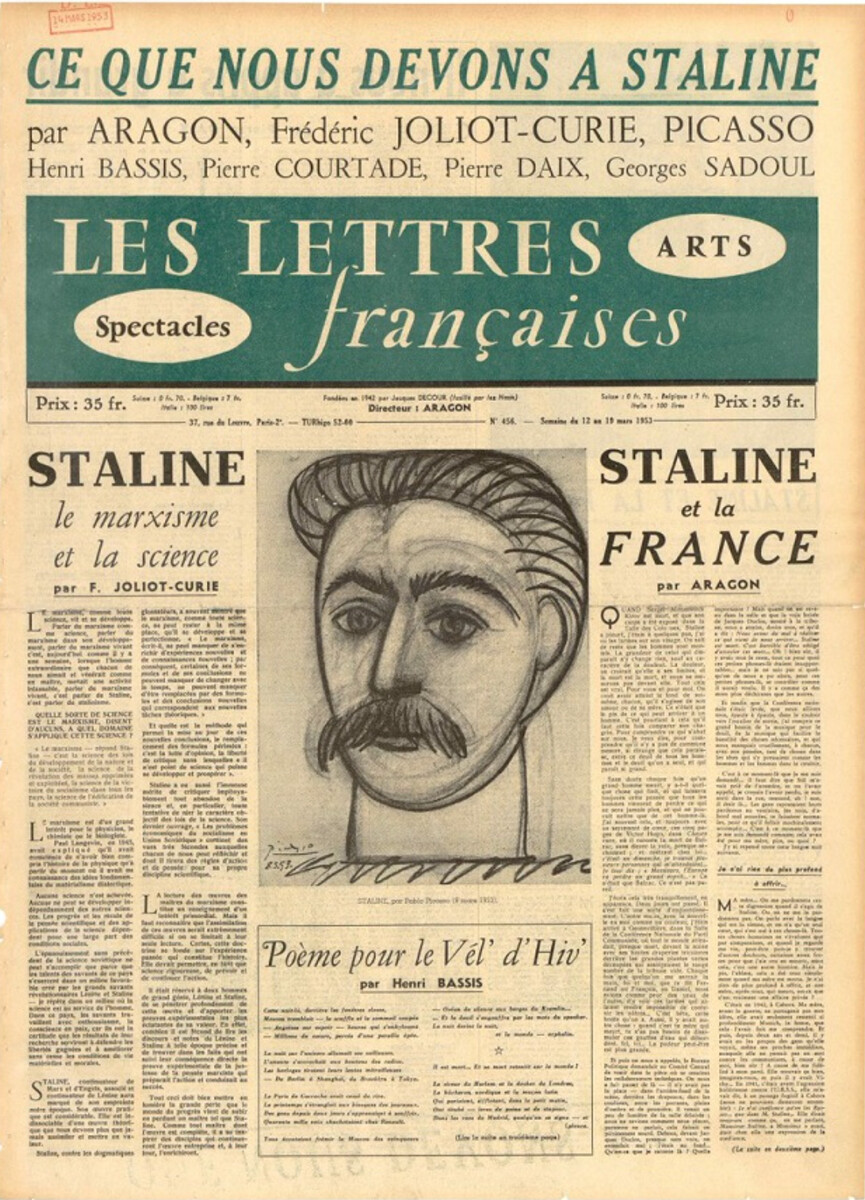

The incident with the birthday greeting didn't cause Picasso and the communists to break off relations. He had been forgiven. The second time Picasso came to draw Stalin was at the insistence of Louis Aragon, a member of the Central Committee of the French Communist Party, following Stalin's death in 1953. A few days after the demise of the "great leader", a portrait of him by Picasso appeared on the front page of the 'Les Lettres Françaises' newspaper.

Picasso drew Stalin using a photograph of him as a young man, with the maximum degree of realism possible for him at the time and depicted him with the eyes of a dreamer and with a strong chin. But, once again, communists didn't appreciate Picasso's efforts and considered the portrait a mockery.

What is more, the artist's handiwork had significant consequences. The Communist Party's outrage was so great that it put out a statement condemning in no uncertain terms the publication of the portrait in the newspaper. French communist publications printed letters from indignant readers complaining that Picasso's portrayal of Stalin was completely divorced from reality. And they regarded his interpretation as an insult to the communist idea.

Internal arguments among the leadership were directed at finding a "scapegoat", but no-one wanted to get involved in investigating the picture. Many people sought to lay the blame on Picasso himself on the grounds that he had chosen such a style of drawing, even though he could have "made more of an effort": for instance, using the works of Soviet artists as a starting point.

In addition to the internal repercussions, the "portrait affair" weakened the standing of the party itself. The hunt for the guilty led to people in leading positions starting to accuse one another of allowing Picasso's drawing to be printed on the front page of the newspaper. French politician and communist Pierre Juquin alleged in an article that the arguments even culminated in Louis Aragon attempting to kill himself.

People who knew Picasso recalled that the artist took it all quite badly. And it wasn't even the "riskiest" picture he could have made. In the aftermath of the row, writer Pierre Daix from 'Les Lettres Françaises' met the artist, who – either in jest, or in earnest – told him that, at some point, he had intended to draw Stalin in the nude.

As art historian Gertje Utley wrote in her book 'Picasso: The Communist Years', Pierre Daix wrote down a short monologue, in which Picasso described how he saw the situation: "Can you imagine if I had done the real Stalin, such as he has become, with his wrinkles, his pockets under the eyes, his warts… Can you hear them scream? He has disfigured Stalin. He has aged Stalin… And then, too, I said to myself, why not a Stalin in heroic nudity? Yes, but, Stalin nude and what about his virility? If you take the pecker of the classical sculptor… so small… But, come on, Stalin, he was a true male, a bull. So, then, if you give him the phallus of a bull and you've got this little Stalin behind his big thing, they'll cry: ‘But you've made him into a sex maniac! A satyr!’"

In the wake of the storm of criticism directed at him, Picasso himself cooled significantly towards the Communist Party, even though he did not cease giving it his material support or stop calling himself a communist.

Several years later, when the crimes of Stalin became known in France and the process of de-Stalinization had begun, Picasso met Pierre Daix and asked him: "I hope now you're not going to say that I drew Stalin too sympathetically?"

Picasso left the Communist Party in 1956, when he learnt that Soviet troops had been sent into Hungary to suppress the uprising there. It happened on the day of the opening of his first exhibition in Moscow. On hearing an official report that troops had gone in, Picasso signed a collective letter of protest and quit the party.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox