The golden age of dirigible balloons, aka airships, fell in the 1910s-1930s – both globally and in the USSR. Their serial production was first established by German entrepreneur Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin. Later, his name began to be firmly associated specifically with airships, for which they were dubbed ‘zeppelins’. Over the entire period of their existence, civilian airships performed about 2,500 flights and carried more than 28,500 passengers.

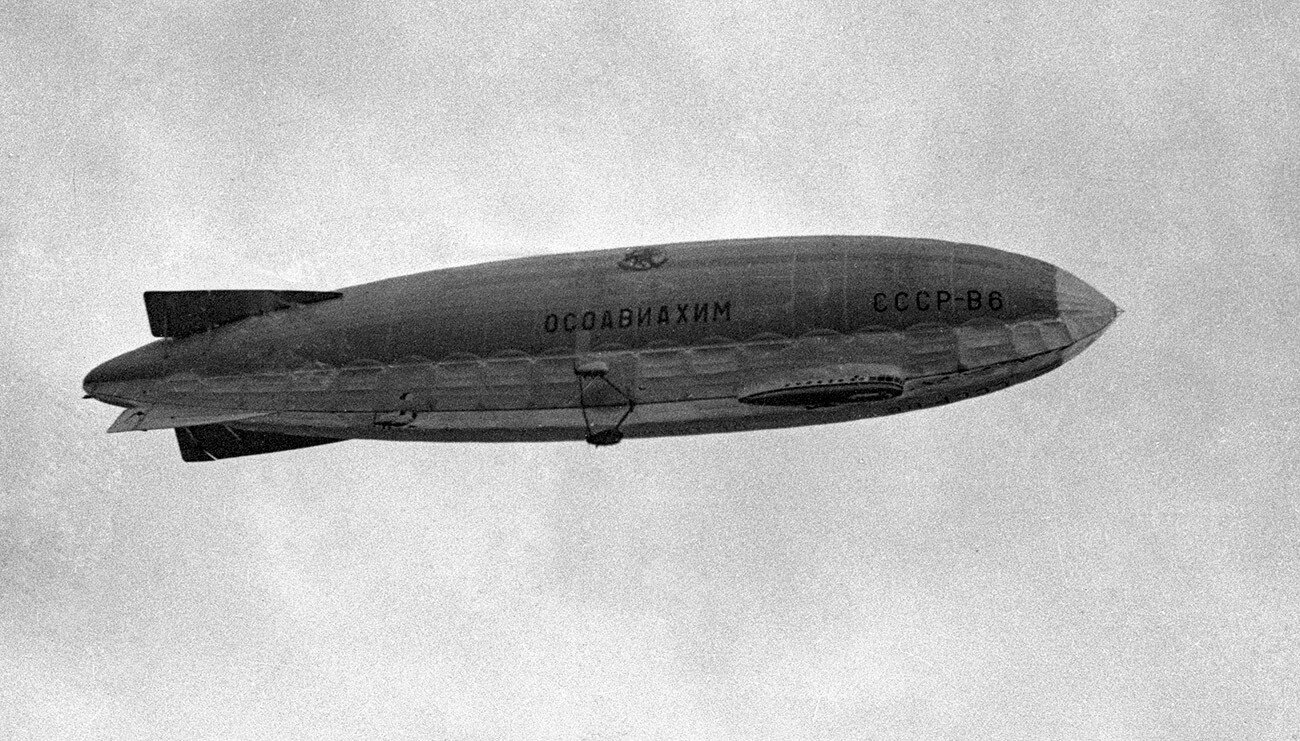

In 1929, the ‘Graf Zeppelin’ airship managed to circle the globe in 20 days with just three intermediary landings. A world record of the length of flight, meanwhile, was set by the Soviet SSSR-V6 OSOAVIAKhIM – it managed to spend 130 hours in the air without landing.

Airships were not only flying longer, they also increased in size and cargo capacity. The most outstanding in its size was the giant Hindenburg-class airship of the 1930s. This airship, comparable to an ocean liner, inspired the thought that a massive nuclear reactor, an engine and heavy biological protection would fit just fine in such a giant.

It was supposed that a nuclear airship would take off like before, with the help of helium, so the mass of the airship itself and the reactor inside of it wouldn’t play a specific role. Because of this, many believed this idea to be quite realistic. The benefits were obvious: thanks to a nuclear power unit, the airship would maintain a constant weight and have an unlimited flight range.

Moreover, nuclear dirigibles offered an opportunity for exploring hard-to-reach territories. Italian Umberto Nobile, who worked in a Moscow Region bureau in Dolgoprudny and who built the ‘Norge’ airship, noted: “The world has at least one more country where airships could be developed and utilized. It’s the Soviet Union with its vast territory, mostly flat… Especially in the north of Siberia, colossal distances separate one settlement from another. This complicates road construction. However, weather conditions are quite favorable for airship flights.”

But, hopes were dashed. At the end of the 1930s, airship construction was simply shut down, due to a spree of large crashes in different parts of the world. For the Soviet airship industry, the case of V-6 was the last straw – ironically, the very airship that set the world record. In 1937, in the conditions of a polar night and rough weather, it lost its bearings and crashed into a mountain.

The crew of the airship USSR-V6

Public DomainIt would seem that lighter-than-air airships compromised themselves completely, but the aircraft industry, to the contrary, showed high promise. But what became of the nuclear project?

Oddly enough, the ambitious Soviet nuclear project was born when, it seemed, dirigibles were abandoned.

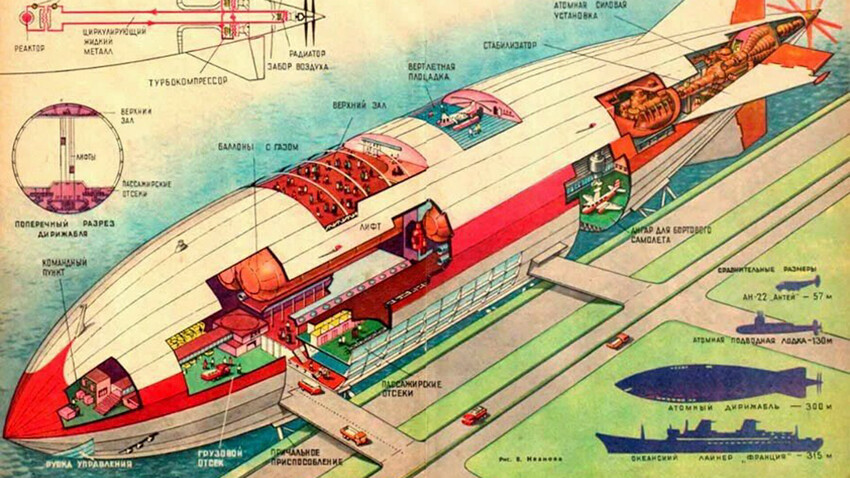

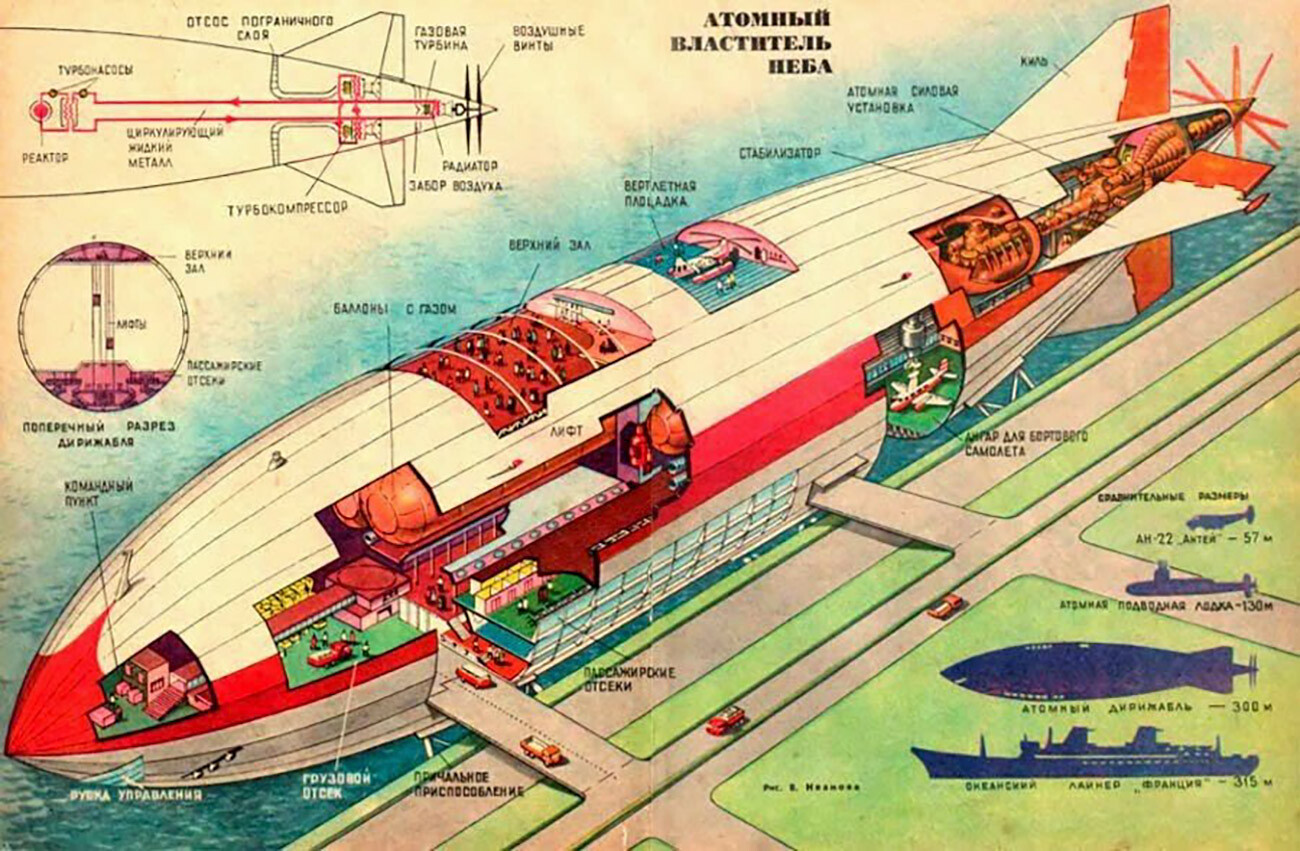

In 1971, Candidate of Technical Sciences Gennady Nesterenko presented a concept of one of the most high-quality and thought-through projects of a nuclear dirigible on the pages of a popular science magazine, ‘Tekhnika - Molodezhi’ (‘Technology for the Youth’).

It was slightly larger than regular dirigibles from the past; however, it could carry much more cargo and passengers. Also, due to the power of its nuclear reactor, the flight speed should also have increased to 200-300 kmph.

Most of all, the creators of the project stressed the comfort levels of the airship. ‘Tekhnika – Molodezhi’ wrote that many people still prefer an ocean liner rather than a plane, despite its slow pace. And that they choose it specifically for its comfort. So why not combine the best sides of planes and ships in dirigibles – speed and comfort?

It was supposed that it would be a 300-meter airship, the size of a nuclear aircraft carrier. One such dirigible would be able to carry 180 tons of cargo or 600 luxury class passengers. With comfort sacrificed, it would be able to accommodate 1800 passengers.

The dirigible would be set into motion by 20-meter propellers and powered by a 200 MW nuclear reactor (a similar one today is installed, for example, on a Russian icebreaker of the Arktika class).

Nonetheless, the project was ultimately left on paper. Neither in the 1970s nor later anyone saw any necessity in it.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox