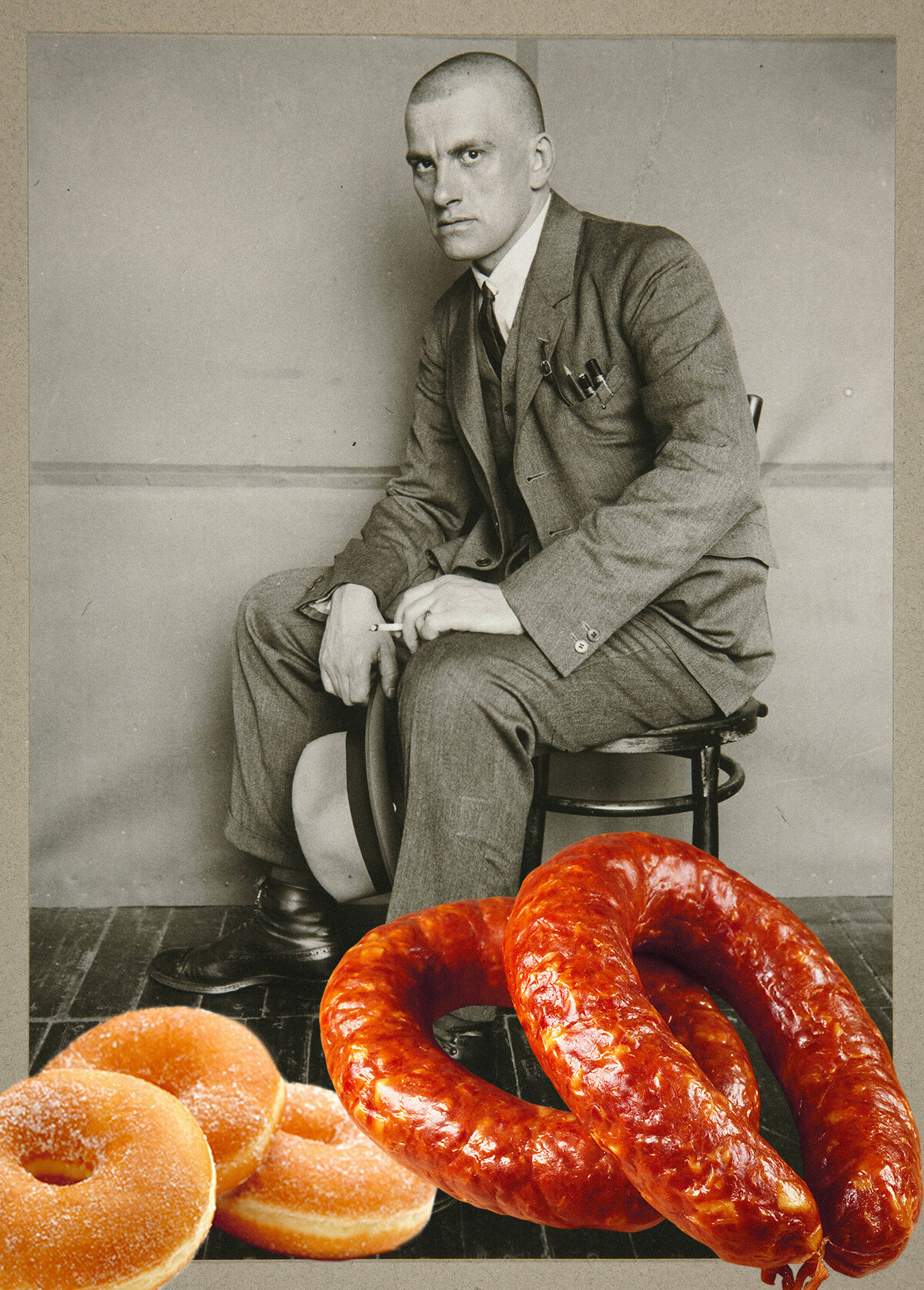

The poet was no foodie: He savored foie gras in a Parisian restaurant with the same interest as ‘shashlik’ (skewered and grilled meat) on the summit of Ai-Petri in Crimea. But his real passion was for simple food – for instance, doughnuts. Mayakovsky loved them from childhood and, in his school days, he would even ask his mother for a bit more pocket money to buy doughnuts for himself and his classmates.

As a young man, he lived on smoked sausage and ‘baranki’ (small, hard bread rolls shaped like a bagel): He rented a dacha in Petrovsko-Razumovskoye (which was then a suburb of Moscow) and set himself a maximum budget for food – three rubles a month. He suspended his rations from the ceiling so that rats didn't eat them and made incisions on them. A half ‘vershok’ (just over two centimeters) of sausage and two ‘baranki’ for breakfast, a whole ‘vershok’ for lunch and another half ‘vershok’ for dinner.

And it was Mayakovsky who gave another poet, Igor Severyanin, the idea for the effervescent image of pineapples in champagne. It was in Crimea at the so-called ‘First Olympiad of the Futurists’. In the course of a dinner party held by poet Vadim Bayan, Mayakovsky dipped a piece of pineapple in champagne, tried it and immediately advised Severyanin to follow suit: "Incredibly tasty!" The first lines of Severyanin's poem (titled 'Overture') were instantly born.

The famous lines about pineapples in champagne are not the poet's only ones devoted to recherché desserts. Of note is the ice cream made with lilacs that he urged people to try: "Here's something nice to eat, people of the square: My products you'll find to your liking!" Poet Pavel Antokolsky once accompanied Severyanin to a restaurant and expected him to order something extremely sophisticated. But, he was shocked when Severyanin asked for a mundane bottle of vodka and a salted cucumber.

There was nothing the author of numerous fables Ivan Krylov, dubbed the ‘Russian La Fontaine’, liked more in the world than eating. To be more precise, his life consisted of an endless round of breakfasts, lunches, dinners and snacks.

Krylov would never stop at a single portion, preferring to consume several plates each of soup and meat chops, as well as innumerable ‘pirozhki’ (small baked or fried buns with fillings) and other miscellaneous treats. He ate pancakes by the dozen, and would often swallow a minimum of 80 oysters at one sitting. At a reception given by the tsarist family, he pretty much breached all conceivable conventions by devouring everything the waiters brought. And he was still unhappy that the portions were too small. And, once, having just finished dinner, he immediately headed home where a hot fish soup awaited him. Knowing his indefatigable appetite, friends and acquaintances tried to cook plenty to spare when inviting Krylov – he was single-handedly capable of eating as much as all the others combined.

The great poet had the most prosaic tastes: His parents were fairly unfussy about food and they instilled the same attitude in their son. Pushkin's nurse Arina Rodionovna used to make ‘kalya’ for him – a thick soup with chicken, vegetables and smoked meats, to which cucumber brine and salted cucumbers were invariably added. Alexander Sergeyevich liked his pancakes to be made in a special way: Beetroot juice was added to the batter, giving them a bright pink color.

While in exile in Mikhaylovskoye, he also did without delicacies, requesting his brother send him "mustard, rum, something in vinegar – and books". In the final hours of his life, Pushkin asked his wife to bring him some cloudberries: He ate a few of them and drank some juice. Soon afterwards he was dead.

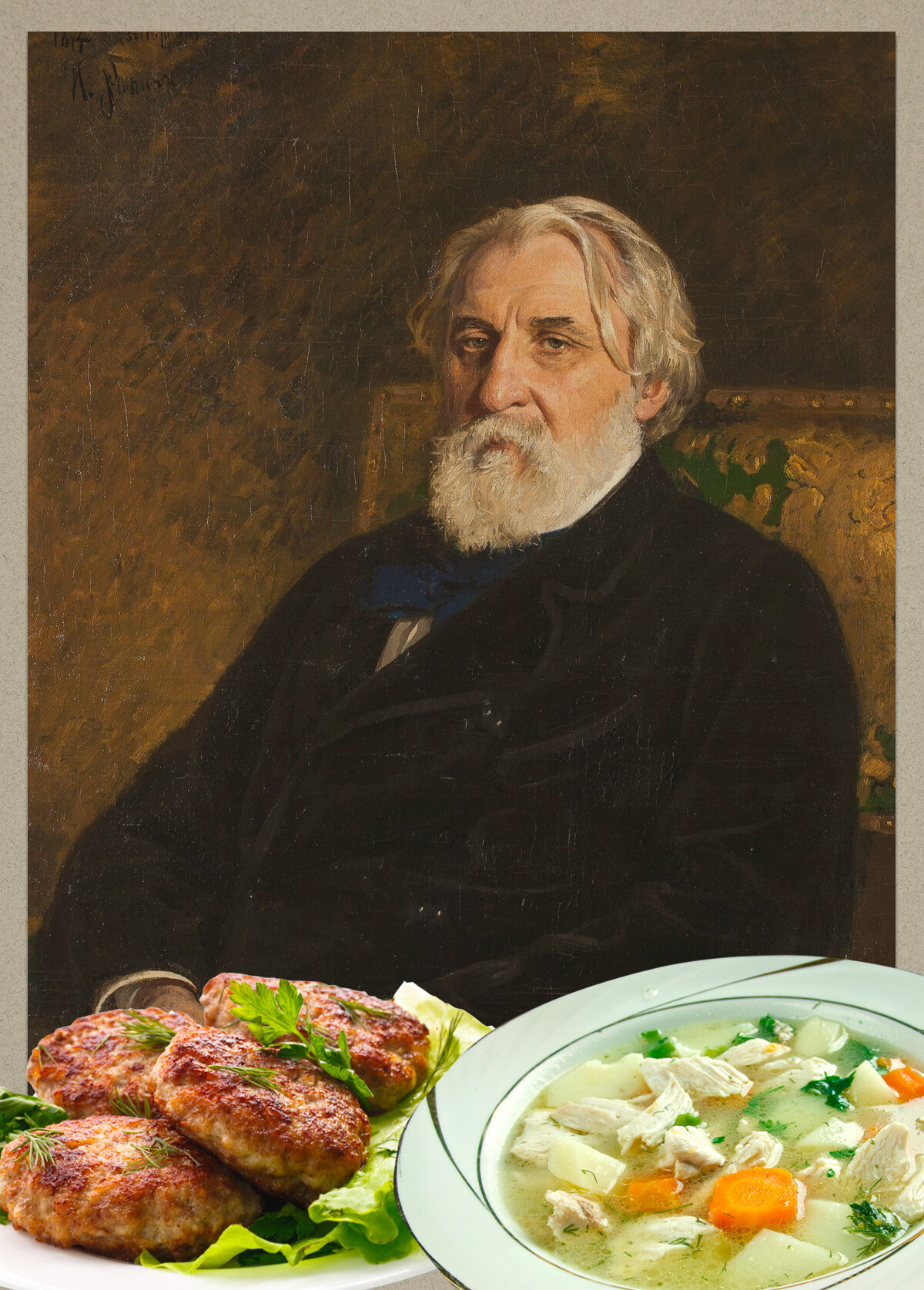

On the Spasskoye-Lutovinovo estate, from childhood, Turgenev didn't want for anything. Exotic fruits from local greenhouses, fish from ponds and lakes, milk and meat – virtually everything found its way to the table. The writer was particularly fond of soups – made with chicken or offal. He once invited poet Afanasy Fet to visit: As they were leaving, Turgenev's mother gave them some food she had prepared for the journey. When the carriage jolted on a bump, the writer began to swear: It transpired that the gravy from the veal cutlets had started seeping onto his medicine chest. Fet was hugely amused by the situation: Holding the cutlets by their bone, he observed Ivan Sergeyevich wiping down the chest, which he never traveled without in fear of being taken ill. When in Paris, Turgenev took part in ‘Dinners for Five’ with Gustave Flaubert, Edmond de Goncourt, Émile Zola and Alphonse Daudet. They convened once a month to discuss literature and try exquisite dishes.

The poet liked his food, but he was also capable of paying no attention to what he was eating. Once, Lermontov's cousin Alexandra Vereshchagina decided to play a trick on him with a female friend and made some pies filled with sawdust. He ate one without noticing the strange flavor of the filling, after which the practical jokers themselves grabbed a second one from him and confessed to their prank. Lermontov was hugely offended.

The poet preferred to eat at home: For dinner, the cook made four or five dishes for him and, for dessert, served ice cream, which Lermontov was very partial to. He had a similar fondness for salted cucumbers. One day, Lermontov managed to get himself invited by a visiting second-rate poet after learning that he had arrived in the Caucasus with a small cask of salted cucumbers. While the latter was reciting his verses, Mikhail Yuryevich ate his cucumbers, stuffed the rest into his pockets and left.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox