Anja Pabst grew up in the town of Schwedt in East Germany. Her parents were friends with a Russo-German family. She played with their son all her childhood and even learned a Russian children's song.

In 1980, Anja and her parents went to the USSR for the first time. They visited relatives of the aforementioned mixed couple in Rostov-on-Don.

"I'll probably say something pathetic, but I didn't feel any boundaries: We were welcome and it seemed that it wasn't contrived. In Germany, friendliness and openness are not always natural, but, for me, these traits are key in my work and in my life."

Anja graduated from a school with an advanced study of the Russian language. On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. A month later, she and her parents traveled to West Berlin for the first time. One of her first impressions was the difference between East Germans and West Germans. "They are still different now," Anja says.

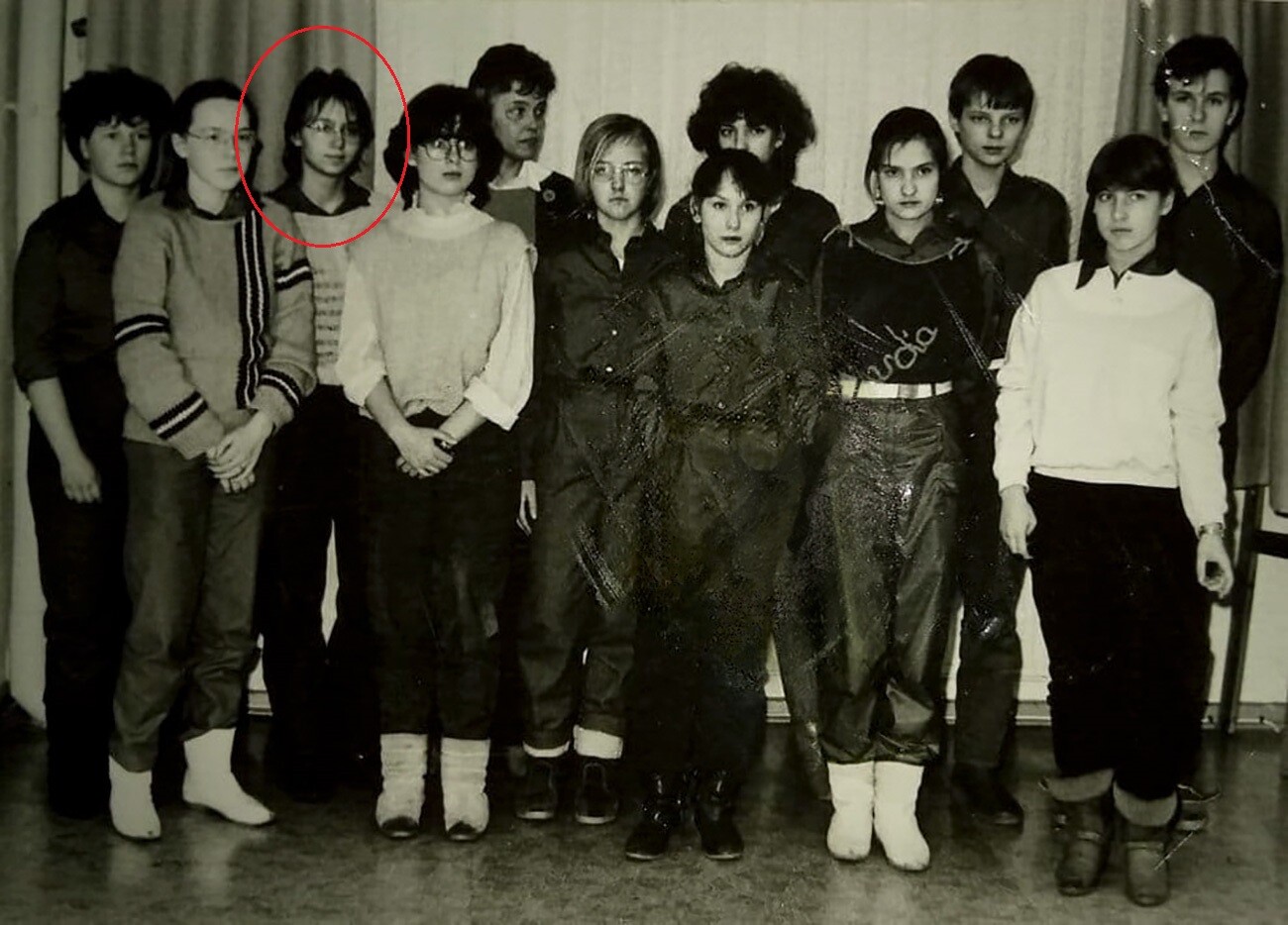

Anja with her German classmates, 1987

Personal archive"I was a pioneer, then a member of the ‘Union of Free German Youth’ (that's our ‘Komsomol’), for me the main value was mutual support. We all supported each other as a team. There was no such thing in West Germany. There, they considered that the closest person to you is yourself; you had to think about personal gain first. Although, of course, there are exceptions."

With a good knowledge of Russian, Anja went to study at the Kaluga Pedagogical Institute. "There were food vouchers in Russia at that time. Me and nine other foreign students teamed up and shared: who stood in which waiting line. My duty was to stand for bread. We ate bread with onions. When I brought butter from Moscow, it was a big celebration. Just like those days, when the boys bought watermelon," she recalls.

It was the early 1990s, a difficult time. Sometimes, there was no electricity for long periods and students at the dormitory had to shower with candles. Once, in winter, vodka was given out on vouchers. Anja stood in line, exchanged the vodka for sugar and took it with her on the night train to the city of Engels, Saratov Region, where her Russian teacher from Germany lived at that moment.

"She was like a second mother to me. Thanks to her, I learned and fell in love with Vysotsky and bards, in general," recalls Anja. “There was a whole backpack of sugar with me. And I fell down under its weight right on the platform. I remember how people helped me, how long it took me to get there… And it was a wonderful experience. So no, it was not boring!"

In 1992, Anja went back to Germany and worked on a program to integrate migrants from the former Soviet Union. But, she was always in touch with Russia, traveling to language camps in Altai and Samara.

Anja returned to Russia in 2004, as she got a job offer to support Germans in the CIS countries. And in Fall 2009, she quit her job and set up her own business.

Anja's house

Personal archiveNow, Anja is a business coach and mediator, helping small and medium-sized Russian businesses solve problems with staffing, sales, clients, goal-setting and efficiency.

"I don't chase money. I live in a village, I live modestly. I don't even have a water supply. If it works out, next year, I'll take care of it and, this year, my house was finally painted anew. And this is an important point for me: the house is in order, now I can afford the luxury of choosing my clients. I don't need much myself, the main thing is that my pets don't starve and that I can buy petrol. That's all," she says.

In Russia, Anja started walking in forest

Personal archiveShe also admits that she is still very much a city dweller, but remote work has allowed her to live in the countryside. "Here, I learned to love silence. I learned how to stoke the stove, how to prepare a bathhouse for steaming. But, the coolest thing I know how to do is chop wood!"

According to Anja, Russian business looks more and more like German business and, over the last 10 years, the law-abidingness of Russian entrepreneurs has increased and there are far fewer gray schemes as there were in the 1990s.

Russian entrepreneurs differ in their efficiency, mobility and ability to think outside the box. Germans lack such creativity. "There is a historical reason for this. When a lot of things don't exist or are forbidden, you learn to look for non-standard solutions. The Russians manage it naturally."

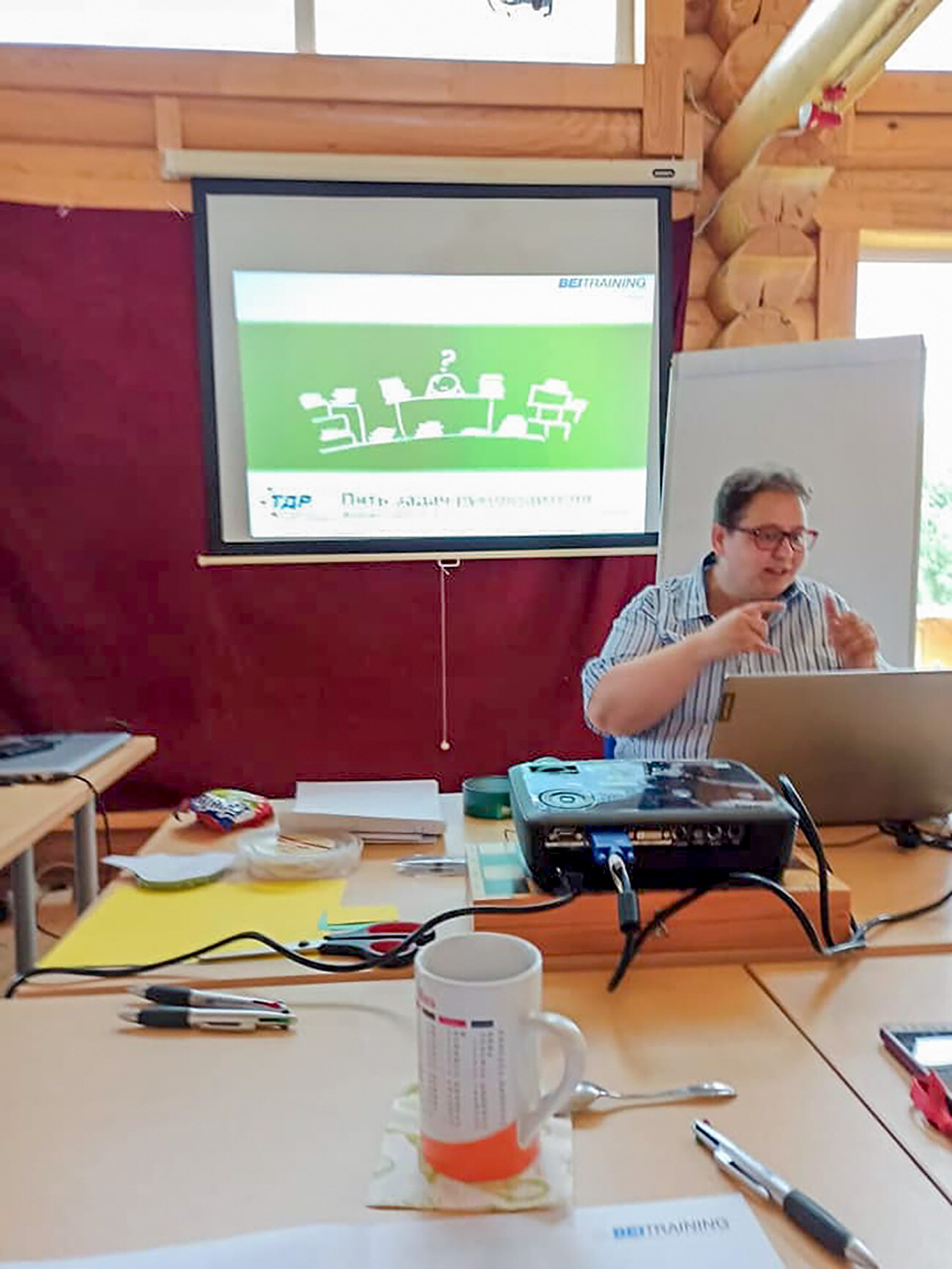

Working remotely from the village

Personal archiveHowever, one German trait is missing: "I would suggest that Russians look through the eyes of the client and think 10 steps ahead. Thoughts like 'let it go how it goes' or 'we'll decide tomorrow' are not always a good thing. Germans think very far ahead, calculate all the risks."

Anja is inspired by the story of Stefan Dürr, founder of the Russian-German agricultural holding company EkoNiva. "I am certainly pleased that my fellow countryman lives and works in Russia, but I also like him very much as a person."

"Thinking several steps ahead, that's what I'm still German for. Although I already have a certain spontaneity. I always follow agreements. And I don't like debts. These things definitely won't change for me."

Sunflowers in the yard

Personal archiveIn addition, Anja does everything on time with German precision and does not like when people are late. And yet, even her German friends have begun to notice that she is becoming more and more Russian in spirit.

Anja's favorite joke is that the stork that carried her as a baby missed by about 2,000 kilometers. Meaning she should have been born in Russia, not Germany.

The full version of the interview was published in Russian in the ‘Nation’ magazine.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox