José Antonio was born in the old Spanish city of Salamanca. His grandfather loved mountain hiking with his dog, particularly hunting partridges. By doing so, he instilled a love of nature in his grandson. As a boy, Jose also went on forest hikes with a family friend, who was a geographer.

For the rest of his life, he would remember hearing the howling of wolves for the first time.

“I thought: how beautiful! Wolves know how to form chords in the sound scale. And, now, by these chords, we can 'read' the animals, even define their number. Well, imagine: A wolf begins to howl, another picks up, then a third, a fourth joins. They have very beautiful and complex choruses.”

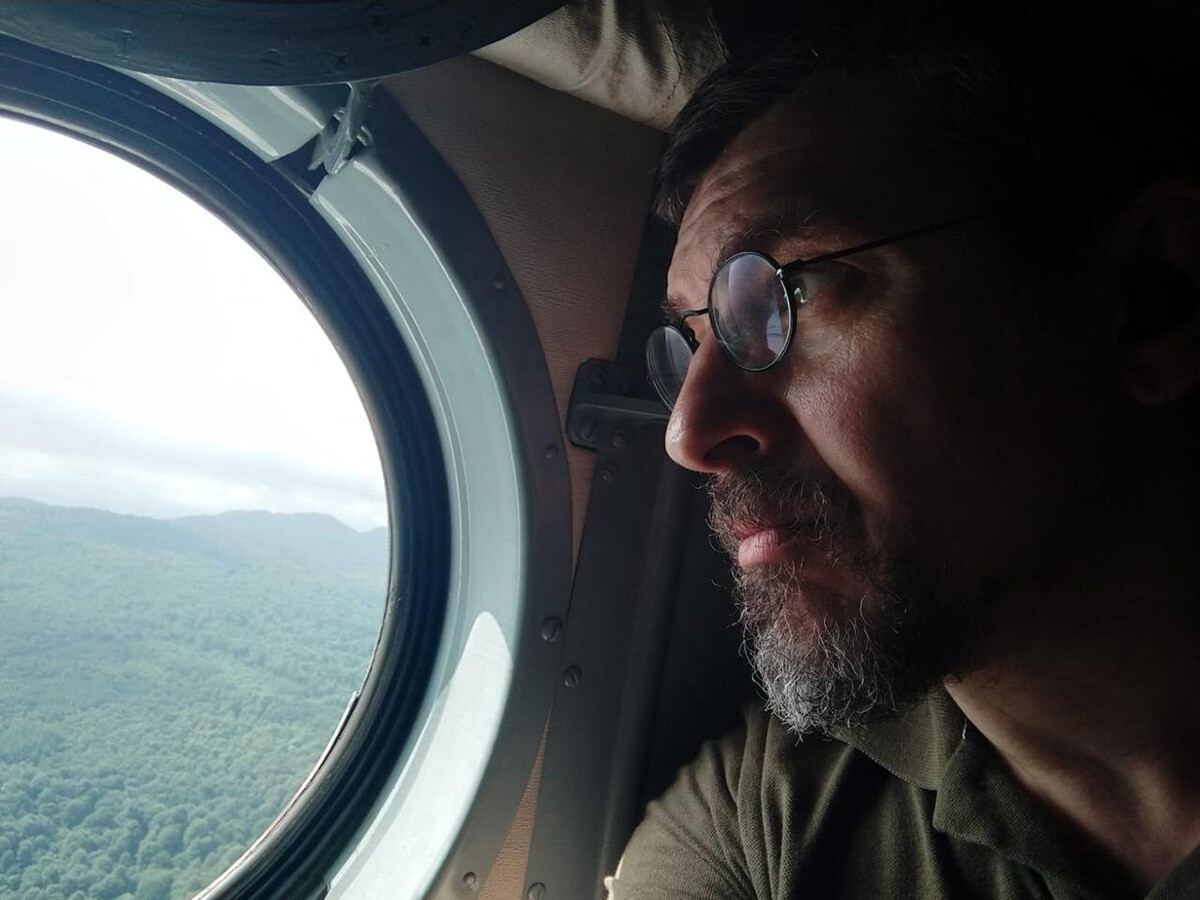

So, Jose decided to become a zoologist. And, now, he is a specialist on large predators and a senior researcher at the Institute for Problems of Ecology and Evolution at the Russian Academy of Sciences and the 'Kaluga Zaseki' Nature Reserve.

He also learned to howl like a wolf. Literally.

Jose studied biology at the University of Salamanca and chose wolves as his specialty.

“It always seemed to me that a zoologist could be more fully realized in Russia, as there is a powerful scientific school there. Therefore, as soon as the opportunity arose, I did not hesitate for a minute. In 1993, from the second year of Salamanca, I transferred to the first year of the biological faculty of Moscow State University.”

At first, like many foreigners, Jose had problems with the Russian language. And also with advanced math. There were difficult times. However, by the third year, the Spaniard felt like a fish in water at the Moscow University.

He liked the respectful attitude of the professors to the students. He liked that, while on expeditions, they lived together and communicated a lot. And studying was genuinely interesting.

But, life itself in the early 1990s in the country was hardly understandable to a foreigner. “And not even because of the different culture – Russia itself was changing,” the Spaniard recalls.

A lot of his fellow countrymen who had lived in the USSR, could not stand it after the collapse of the country and left. But, Jose stayed.

Russia is the leading country in the world in terms of the number of wolves. There are at least 65,000 of them there. It is not surprising that there are dozens of proverbs about these animals. But, Jose laments that the wolf has long been considered a harmful animal.

“The dawn of this theory came in the post-war period. During World War II, wolves really often attacked people, because there were many wounded and dead left in the fields. To some extent, the animals got used to such prey, although it was not typical for them. In 1943, the USSR began shooting wolves from airplanes and, in 1958, a competition was announced for the destruction of these predators; and, a couple of years later, they began to use a new poison. According to modest estimates, more than 1.5 million wolves were destroyed at that time. It wasn't until the mid-1980s that numbers began to recover.”

The restoration is the merit of nature reserves, among others. In 'Kaluga Zaseki', where Jose works, there are about 30 wolves. And almost every one of them has a GPS collar. It weighs only 400 grams and the animal quickly gets used to it.

“Thanks to the collars, we learn a lot about the life of wolves. We have, for example, data that the animal ran for nine hours straight. No big cat can do that, they need to take rest breaks. In the steppes of Kalmykia, we recorded a wolf record: it traveled 90 km in a day. The average daily walk is about 30 kilometers and, in the forest, about 14.”

Jose has been working in the 'Kaluga Zaseki' Nature Reserve since 2000. And he is very happy with life in this southern taiga. When he first started working, he settled with his family in a village house.

“My colleagues joke: Jose is a rare person who loves the harsh Russian winter, that's why he ran away from hot Spain. It's true. I'm waiting for the snow to arrive!”

His father accustomed Jose to manual labor, so he knows how to weld metal and work with wood.

In many ways, the zoologist has become Russian himself. “My scientific supervisor at Moscow State University once said, looking at me: 'He was once an intelligent Spanish guy'."

However, he still remains a Spanish guy, at least in that he still loves Spanish cuisine very much.

The full version of the interview was published in Russian in the ‘Nation’ magazine.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox