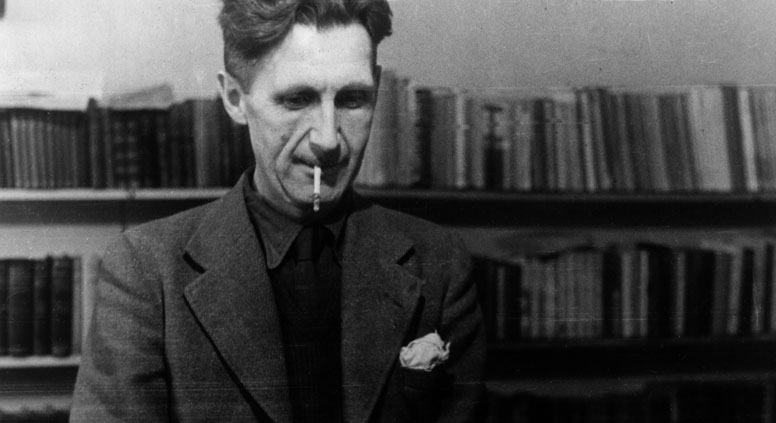

Orwell’s 1984 VS Zamyatin's We. Source: Getty Images/Fotobank

In 2013, sales of George Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” skyrocketed in the United States following Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA’s extensive spying program, and the book seems to be more prescient as time goes on. But before Orwell wrote his futuristic nightmare, he had read the dystopian novel “We” by Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin. This novel first explored the possibility of love and freedom in a totalitarian state and introduced the concept of a single – allegedly benevolent – leader that would form the template for “Big Brother.”

Reduced to a number

Yevgeny Zamyatin wrote “We” between 1920 and 1921. He read some chapters in public and even announced the book’s publication. However, Glavlit, the fledgling Soviet country’s censorship office, swiftly banned the novel. However, as with many other suppressed works, it was transported abroad, eventually being published in New York in 1925. It was published in Prague soon after, and in 1929 a French edition was produced in Paris. The publication of “We” abroad was considered an act of treason, and Zamyatin endured such political problems that, with Stalin’s permission, he left Russia for Paris in 1931, living there until his death in 1937. It would be another half a century before the novel that secured his place as one of the most renowned 20th-century Russian authors was published in his home country.

Just as Zamyatin drew inspiration from both H. G. Wells and Dostoevsky for “We,” so Orwell drew inspiration from him. The details may be different, but the overarching plots of the two works are remarkably similar. Like Winston Smith, Zamyatin’s protagonist, D-503, writes a diary to reflect on his world – in the case of “We” the mathematically perfect OneState where everything is geometrical and the objects, including homes, are made of glass, and the citizens have numbers instead of names. The government is embodied by a single leader, the Benefactor – who is similar to Big Brother – and the Guardians safeguard the country’s security just as the Thought Police patrol the world of “Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

The State newspaper, like Time in Orwell’s work, is the only source of information. Like Winston and Julia, when D-503 meets the female citizen I-330, who leads the counter-revolutionary movement, his world is turned upside down. After they make love, D-503 has a revelation: “For the first time in my life, I get a clear, distinct, conscious look at myself; I see myself and I am astonished …” After overcoming the hurdle of mathematical certainty, the engineer can only long for the forbidden freedom.

Although Zamyatin’s vision is ultimately pessimistic, the book’s satire and Gogol-like humor mean that it is nowhere near as bleak as Orwell’s. The citizens of OneState may not be free, but they live happily, protected from wild nature by the Green Wall. “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” however, depicts a society demonized by hunger, cruelty and pain. Orwell’s experience fighting against Franco in the Spanish Civil War increased his distrust of any political power, which he saw as existing only to preserve itself – at any cost. “We” served as a model to describe his historical period under the guise of a future apocalyptic world. As Umberto Eco explains in his essay “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” “At least three fourths of what is told is not a pessimistic Utopia, it is history.”

A brand new work?

In his article “Freedom and Happiness,” published in London in the socialist magazine Tribune on Jan. 4, 1946, George Orwell acknowledged how thrilled he had been to read “We” – despite having to read it in French. “It is astonishing that no English publisher has been enterprising enough to re-issue it,” he wrote.

Orwell was also surprised that no one had picked up that “Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’ must be partly derived from it.” After listing what he considers the weak points in Huxley’s work, Orwell states: “Intuitive grasp of the irrational side of totalitarianism – human sacrifice, cruelty as an end in itself, the worship of a leader who is credited with divine attributes – that makes Zamyatin’s book superior to Huxley’s.”

Everything seems to indicate that Huxley did read Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel before starting work on “Brave New World,” although he always denied it. “Oddly enough I never heard of Zamyatin’s book until three or four years ago,” he wrote at the time. Given the similarities to Zamyatin’s book, many critics and fellow writers remain unconvinced. Referring to his first novel “Player Piano” (1952), a dystopia about automation, Kurt Vonnegut said, “I cheerfully ripped off the plot of ‘Brave New World,’ whose plot had been cheerfully ripped off from Yevgeny Zamyatin’s ‘We.’”

Analyzing “We,” Orwell contended that perhaps “Zamyatin did not intend the Soviet regime to be the special target of his satire. Writing at about the time of Lenin’s death, he cannot have had the Stalin dictatorship in mind. … What Zamyatin seems to be aiming at is not any particular country but the implied aims of industrial civilisation.” The British writer Martin Amis shares this opinion: “For a while, one entertains the extraordinary thought that ‘We’ is not a futuristic satire on mature Soviet tyranny so much as a gentle lampoon of British utilitarianism. The Benefactor, the Big Brother in ‘We,’ is Lenin all right; but he is also Dickens’ Gradgrind, hideously magnified.”

The writer versus the leader

In 1932, after leaving the Soviet Union, Zamyatin himself clarified what he had been aiming to achieve in his work: “This novel signals the danger threatening man, the State – any State.” It is significant that Zamyatin, despite now being an émigré, did not cite the Soviet Union as the model for his OneState. Perhaps this could be because he conceived the book while he was living in Newcastle in the UK, supervising the construction of icebreakers before the revolution. He saw the seeds of OneState in the very same place Lenin found the inspiration for building his Soviet system – Europe.

Zamyatin was one of the very few writers who dared to openly criticize Lenin, blaming him for embracing Taylorism – a doctrine that was widely popular in Britain. The Bolshevik leader hoped that the rational organization of the production line would produce new workers, true “living machines” that would make socialism a reality. H. G. Wells arrived at the same conclusion during his first visit to Moscow in 1922. After speaking with Lenin, he declared, “Lenin, like a good orthodox Marxist denounces all ‘Utopians’ but has succumbed at last to Utopia, the Utopia of the electricians.”

Zamyatin never returned to his home country, although he represented the Soviet Union at the 1935 International Congress for the Defense of Culture in Paris. His ideas, however, had crept into the country through Huxley and Orwell’s great dystopian works. Both novels, with their conscious or “coincidental” echoes of Zamyatin, were hugely popular among Soviet dissidents and the intelligentsia, and so his ideas subtly chipped away at the foundations of totalitarian ideology. And, like the books it inspired, “We” is just as relevant today as it was back at the dawn of the “new” age in the 1920s.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox