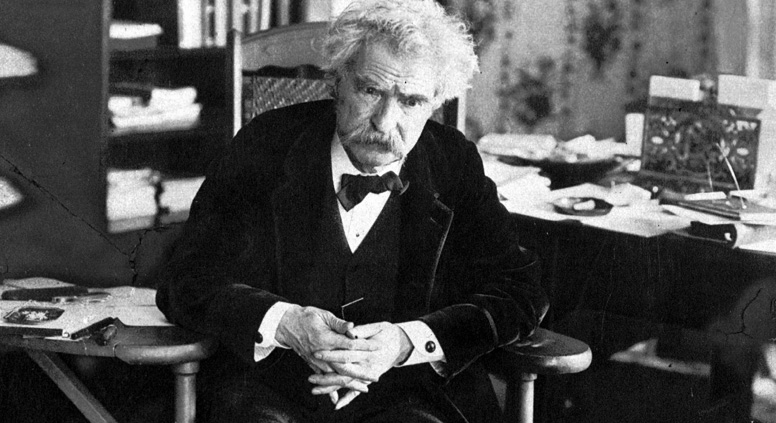

Mark Twain: 'America owes much to Russia for her unwavering friendship in the season of her greatest need.' Source: AP

Mark Twain visited Russia with a group of Quakers in 1867, who described themselves as “a handful of citizens of the United States, traveling for recreation.” In Sevastopol, the “fragments of houses” still showed the effects of siege during the Crimean War, described in Tolstoy’s “Sevastopol Sketches.” The group scoured the area for trinkets and mementos of the famous conflict. “There was nothing else to do,” Twain reports in “Innocents Abroad,” “so everybody went to hunting relics.”

Meeting the Tsar

Twain had lost his passport before visiting Russia, and his arrival was accompanied by “fear and trembling...a vague, horrible apprehension that I was going to be found out and hanged.” Years later, he published a short story reminiscent of these fears. In “The Belated Russian Passport,” the hero worries his lack of a passport will lead to detention:

“In a few hours I shall be one of a nameless horde plodding the snowy solitudes of Russia... bound for that land of mystery and misery and termless oblivion, Siberia!”

Luckily no such fate awaited Twain and his fellow tourists, who “met with nothing but the kindest attentions” after arriving in Russia. They were given a warm welcome in Sevastopol and Odessa, and granted an audience with the Tsar in Yalta.

The tourists elected Twain to address Tsar Alexander II on their behalf. Alexander had ruled to emancipate the serfs a few years earlier, and Twain's speech praised him for “so great a deed.” He also mentioned Russia's support during the American Civil War. “America owes much to Russia,” Twain said, “for her unwavering friendship in the season of her greatest need.”

Twain remembered his meeting with the Tsar as a strange encounter. Even though “a countless multitude of men would spring to do his bidding,” Alexander II had seemed “like the most ordinary individual in the land.” His response to this brush with power was characteristically playful:

“If I could have stolen his coat, I would have done it. When I meet a man like that, I want something to remember him by.”

Revolution from afar

Twain was impressed by Alexander’s simple demeanor, so unlike the “tinsel kings of the theatre.” However, he became disillusioned at news of the increasingly oppressive regime of the Tsar’s successor. In “Letter from a Dog,” Twain wrote that the Tsar’s powers “are a theft today, just as they were when they came originally into his family.”

Although his approach to race relations in his own country has been questioned, Twain considered himself a revolutionary. He was part of a circle of authors eager to support revolution in Russia, and met Sergei Stepniak, founder of the revolutionary publication Free Russia, on his visit to America in 1891.

When Maxim Gorky traveled to New York in 1906, Twain joined several high-profile literary figures at a dinner to honor the Russian author. Gorky had traveled to America in hope of raising funds for revolution, and Twain's welcome speech echoed his address to the Tsar years before. This time, he compared the situation in Russia to the American revolution:

“Anybody whose ancestors were in this country when we were trying to free ourselves from oppression must sympathize with those who now are trying to do the same thing in Russia.”

Twain praised Gorky’s writing, and the Russian author returned the tribute. A New York Times article quotes Gorky’s statement that Twain had “proved an inspiration,” adding that “it is part of the liberal education of Russia to read Mark Twain's works.”

Scandal in New York

Despite the promising beginning, relations between Twain and Gorky were disrupted by scandal. Gorky was not officially married to his companion Maria Andreyeva, who had accompanied him to New York, and the pair were evicted from their hotel in the middle of the night.

Twain’s reaction to the scandal suggests that the rebellious spirit evident in his joke about stealing the Tsar's coat had given way to greater conservatism. “I am in hearty sympathy with the Russian revolutionists,” he told the New York Sun, but “we have certain conventions and standards of conduct and Gorky should have been made aware of the views the American people hold in this matter.”

Gorky left America disappointed by the lack of support for his cause. However Tova Yedlin’s biography suggests he did not blame Twain. “He is a wonderful person,” Gorky wrote to friends, “but he is old, and old people often cannot understand clearly the meaning of things.”

Twain continued to attract the admiration of Gorky and many other Russian authors, and remained greatly interested in Russian affairs until his death in 1910.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox