English poets honor Joseph Brodsky

|  |

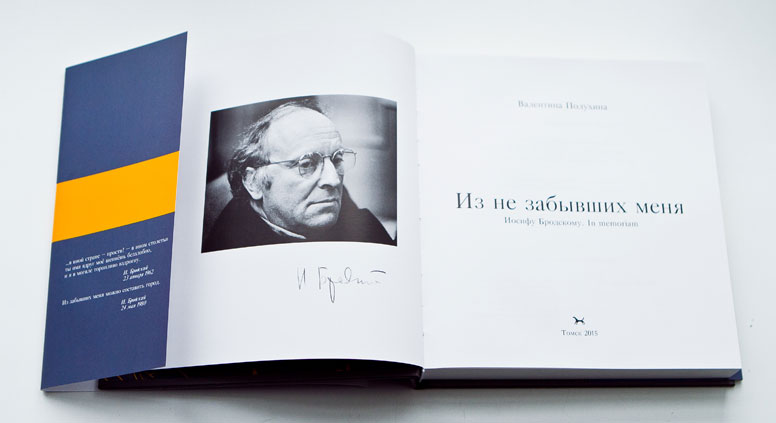

| Valentina Polukhina. Source: Alexander Korolkov / RG | From Those Who Remember Me. Source: Tomsk State University |

Russian poet Joseph Brodsky would have turned 75 this year. To commemorate this, a Tomsk publisher has issued a book of poems From Those Who Remember Me. Brodsky once wrote ‘Those who forget me would make a city’, but this anthology proves there are many more that remember him.

“Over the years I have collected several hundreds poems dedicated to Brodsky by poets from all over the world”, British-Russian scholar Valentina Polukhina, who was a friend of Brodsky, told RBTH. Three years ago, Polukhina decided to issue an anthology of these poems and selected 115 Russian and 55 foreign poets, asking some to compose verse especially for the commemorative book.

"When I approached British poets none refused since all of them either knew Brodsky personally or admired his work. I am proud to say that two of 18 British poets are the patrons of my charity - The Russian Poets Fund - the former Archbishop of Canterbury Baron Rowan Williams and a former Poet Laureate of UK - Sir Andrew Motion,” Polukhina says.

Born in England, American citizen Wystan Hugh Auden (1907-1973) was regarded by many critics as one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. He was also a prolific writer of prose essays and reviews on different subjects.

“W. H. Auden met Brodsky in Vienna and brought him to London Poetry International Festival of which Daniel Weissbort was one of the organizers,” Polukhina said.

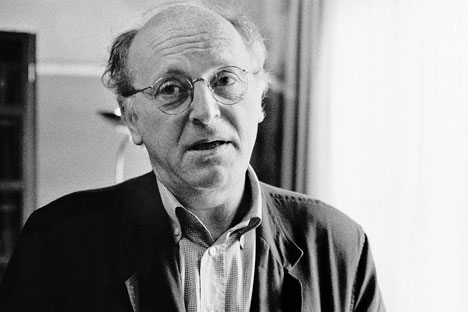

Photo:Joseph Brodsky. Source: Opale / East News

W. H. Auden, Foreword to Joseph Brodsky “Selected Poems” (Penguin Books, 1973

One demands two things of a poem. Firstly, it must be a well-made verbal object that does honor to the language in which it is written. Secondly, it must say something significant about a reality common to us all, but perceived from a unique perspective. What the poet say has never been said before, but, once he has said it, his readers recognize its validity for themselves.

…My chief reason for believing that Professor Kline’s translations do justice to their original is that they convince me that Joseph Brodsky is an excellent craftsman… Mr Brodsky commands many tones of voice, from the lyric (A Christmas Ballad) to the elegiac (Verses on the Death of T. S. Eliot) to the comic-grotesque (Two Hours in an Empty Tank), and can handle with ease a wide variety of rhythms and meters, short lines, long lines, iambics, anapaestic, masculine rhymes and feminine…

About the uniqueness and, at the same time, universal relevance of a poet’s vision, it is easier for a foreigner to judge, since this does not primarily depend upon the language in which it is written.

Mr. Brodsky is not an easy poet, but even a cursory reading will reveal that, like Van Gogh and Virginia Woolf, he has an extraordinary capacity to envision material object as sacramental signs, messengers from the unseen…

He is a traditionalist in the sense that he is interested in what most poets in all ages have been interested in, that is, in personal encounters with nature, human artifacts, persons loved or revered, and in reflections upon the human condition, death, and the meaning of existence.

Daniel Weissbort (1935-2013) was a co-founder of the journal Modern Poetry in Translation. He published anthologies of Russian Poetry of XX Century, and with Valentina Polukhina - An Anthology of Contemporary Russian Women Poets (2005). His memoir of the late Joseph Brodsky is entitled From Russian with Love.

Daniel Weissbort (1935-2013) was a co-founder of the journal Modern Poetry in Translation. He published anthologies of Russian Poetry of XX Century, and with Valentina Polukhina - An Anthology of Contemporary Russian Women Poets (2005). His memoir of the late Joseph Brodsky is entitled From Russian with Love.

Joseph Brodsky. Source: EPA

Daniel Weissbort

You were among us, Joseph…

I think, biblically.

At least, that is what springs in mind.

Like a child, a different being,

strangely unprotected, unprotectable,

and so with that tough-guy stance.

Tender. Well, there is no need to think of it,

because you said it yourself.

Your tenderly, with tenderness —

I wince now, as I did then,

The word, resuscitated in our language,

yours as much as mine.

Nothing to do with flower children,

with reimagined gender roles.

To do with language simply.

You were, found yourself,

among us, were there to be found,

were found, belonging,

more so than the indigenous even…

Because you changed wherever it was you were.

We did not believe, couldn’t,

yet accepted the fait-accompli.

Its saving virtue that,

our acceptance of the fait-accompli.

An accomplished fact, then, Joseph,

and somehow we found ourselves in the middle

of a conversation with you,

as we were when suddenly

you were an absence in our lives.

1996

Peter Jay (born in 1945) was Assistant Director for the London Poetry International Festivals from 1969–73. He has edited several anthologies of poetry and

Peter Jay (born in 1945) was Assistant Director for the London Poetry International Festivals from 1969–73. He has edited several anthologies of poetry and

translations.

He has also published Weissbort’s memoir From Russian

with Love.

Joseph Brodsky in Washington D.C., October 1991. Source: AP

Peter Jay

Lifelines

to Joseph Brodsky, for our joint birthday

Fragments about the lost or dead

Hung in the air; wandering overhead

A disembodied voice drawled on

Snaring our talk with talk of revolution.

You groped for foreign words, orphaned

In a cold bar, a solitary no-man’s-land,

And haltingly you read to me

Translating your translation of The Flea.

What’s freedom but the rule of poetry?

Such separate worlds in this combine,

Making a new world, neither yours nor mine,

Where sense may apprehend and search

What we in our twin closed spheres cannot reach.

So we are entangled, when we’ve done

Marvelling at the quick net of a pun,

In the still life of poetry,

Through which we climb to common territory

By lifelines rhymed in triple sympathy.

1974

“The origin of the poem is backstage at London’s Royal Festival Hall at the Poetry International Festival of 1972, when Joseph made his first appearance in England. My job as assistant director was mainly to keep the poets happy, help them in practical ways with transport etc., and make sure they knew where they should be and when. So I came to be keeping Joseph company before or after his reading, I forget which.

“The opening describes hearing in the background over the PA system the voice of a poet reading onstage (it was Robert Lowell). I discovered that Joseph and I shared a birthday – he was five years older than me – and his passion for the English Metaphysical poets. So my poem becomes a double homage by using the stanza form of John Donne’s ‘The Flea’, which as it mentions he had translated. The Donne pun (‘done’), was John Donne’s own, but Andrew Marvell as far as I know did not use ‘marvelling’,” the author comments in the anthology.

Rowan Douglas Williams (born in 1950) is an Anglican bishop, theologian and poet. From 2002 until 2012 he was the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury.

Rowan Douglas Williams (born in 1950) is an Anglican bishop, theologian and poet. From 2002 until 2012 he was the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury.

On 26 December 2012, 10 Downing Street announced Williams' elevation to the peerage as a Life Baron, so that he could continue to speak in the Upper House of Parliament.

Dr. Williams speaks fluent Russian and has published several books on V. N. Lossky and F. M. Dostoevsky. As a poet he published three collections of poems.

A monument near the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. Source: PhotoXpress

Rowan Williams

Waters of Babylon: i.m. Joseph Brodsky

Tomi

One of them sat by the Black Sea,

his tongue dry from its stillness, afraid

that moisture on the buds would drown him

in a flood of tastes remembered, in a chaos

of pasts slipping from their triste moorings; afraid

of the toothbreaking dialects around him,

the grinning mouths flecked with food

he could not swallow. By the salt sea

he dried and slept; salted, hanging.

Babylon

And another, peeling the willow bark,

nails stained with green shreds, to plait

a basket, to place in it the eggshell-delicate

hopes of the day when they too will know

how a future can be extinguished, crushed like eggs,

the songs recorded for a grinning themepark,

he weaves away, nodding and smiling at his audience,

and the fast drops leak like a darting tongue

from the basket, green as a snake.

Venice/AnnArbor/Hudson

And another, walking by the lagoons,

by the campus lakes, the river at the street’s end,

his hunger is too fierce, his mouth overflows,

the chewed fragments scattering as he closes

teeth on words from the world’s other side,

grinning and shameless, paid (he says) to wear out

the patience of the young, the solemn, the embarrassed:

he eats and eats until he cannot talk any more, ginger

hot in the mouth. And the moist muscles swell and burst.

2013

George Szirtes was born in Budapest in 1948 and came to England as a refugee at the age of eight. His translations from Hungarian poetry, fiction and drama have won numerous awards. Szirtes lives in Wymondham, Norfolk, and teaches at the University of East Anglia.

Brodsky in 1994. Source: Alamy / Legion Media

George Szirtes

Sorrow

Everything has its limit, including sorrow

Joseph Brodsky

Everything has its limit, including sorrow

that hides in the margins and prefers life narrow:

nothing is written there except marginalia

of misery and impotence and failure

Joseph, I heard you as one of my own kind

a foreigner whose parts of speech were blind

but never deaf nor even could be dumb,

who choked on the cold sea that left him numb,

the numbness I felt in that wan flat voice

so perfectly tuned to loss, that might rejoice

in its own glumness and its soenic lust,

its Audenesque reply to the unjust.

From Mandelstam to Frost the moral route

is that which fits the voice to the cheap suit

of clothes one carries in one’s battered case

to fit occasions and, sometimes, one’s face.

Great hero, Joseph, your mind as deep and wide

as any sea a man might sleep beside,

your angel noises move into dear

that any human ocean yearns to hear.

2013

Lachlan Mackinnon (born in 1956) is a Scottish poet, critic and literary journalist. Until 2011 he was a lecturer in English at Winchester College. He has published several collections of poetry, critical studies and biographies.

Lachlan Mackinnon (born in 1956) is a Scottish poet, critic and literary journalist. Until 2011 he was a lecturer in English at Winchester College. He has published several collections of poetry, critical studies and biographies.

During the Nobel Prize ceremony. Source: AP

Lachlan Mackinnon

An eye drinks a seascape as cranes clang

through the smog of an early morning

in the thrice-named city your teenage

years erupt out of. You are fifteen.

You walk out of school. You are next seen

in court. A servile and obtuse judge

demands who licensed your poethood.

You belong to no union. God

perhaps? Your answer finds no purchase.

You are sentenced. Internal exile.

But you survive. External exile.

Auden finds you work in a college

and you flourish in Michigan, that

cold place, Venice, Manhattan, and at

Byzantium - anywhere tonnage

harbours you find a momentary

stay. Against confusion, poetry

erects itself in search of knowledge.

Your baroque elaborate stanzas

show us a place no whit the Kansas

or New York or an exile’s village:

a cold, northern, invented city

a tsar created, where a party

proved the noblest dream can turn savage.

Sentences taut with syntax, metre

that freezes time like architecture;

what is left of a man is language.

1996

Read more: Joseph Brodsky's love of poetry in English

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox