Badaber uprising: When Russian POWs took on the Pakistani army and the CIA

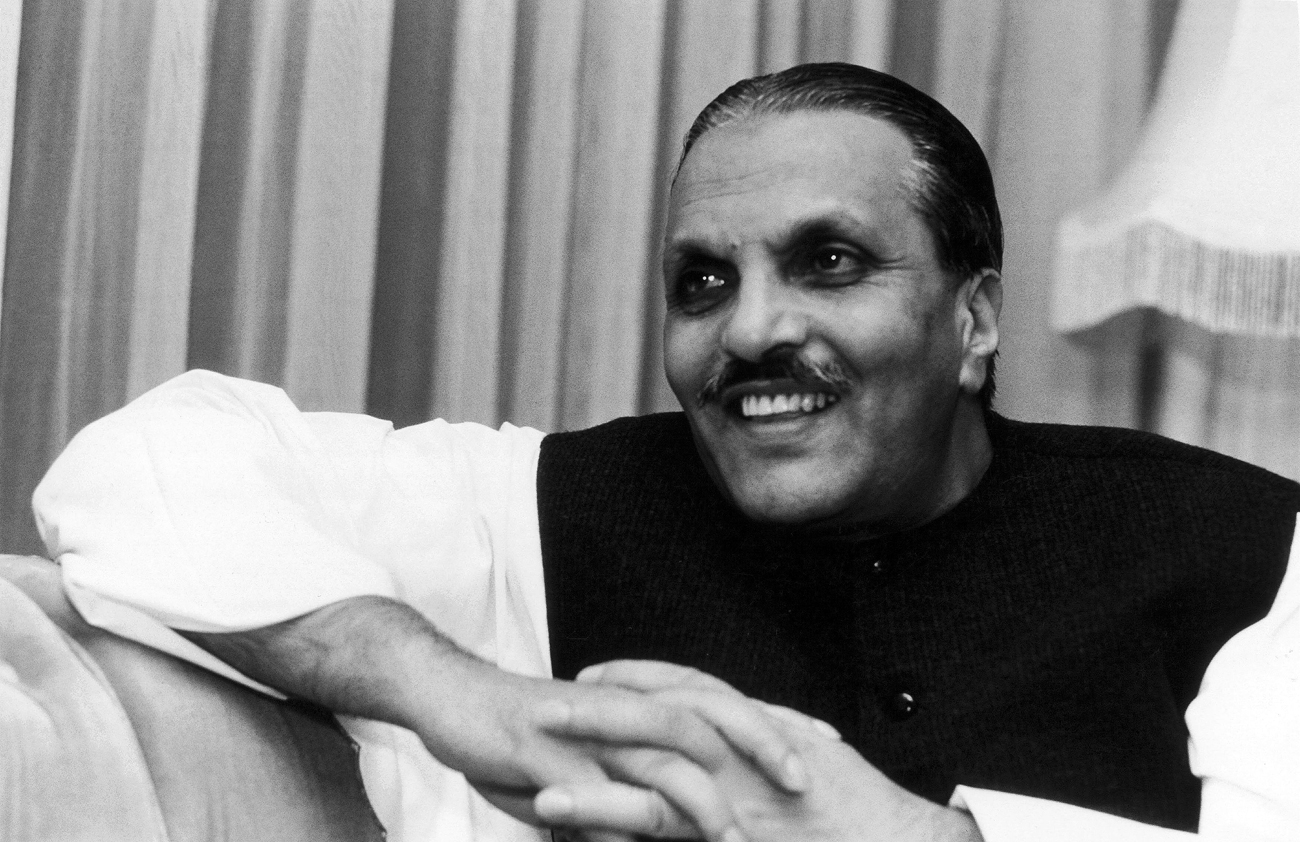

General Zia-Ul-Haq tried to stop the Pakistani media from reporting about the Badaber Uprising.

Getty ImagesIn his autobiography titled ‘In the Line of Fire: A Memoir,’ deposed Pakistani dictator Gen Pervez Musharraf boasts about how Pakistan did something that neither Napoleon nor Hitler could do - defeat Russia in a war. Musharraf was talking about Pakistan’s role in the war to evict the Soviet Union from Afghanistan.

While the generals in Rawalpindi now talk openly about their exploits in that conflict, in the 1980s Pakistan tried to deny playing a direct role. In the spring of 1985, 12 Soviet troops, along with 40 Afghan soldiers were secretly imprisoned in the Badaber Fortress, a military training center set up by the CIA for Afghan Mujahideen.

“Soviet intelligence officers knew of their capture but were unable to pinpoint where they were being imprisoned,” Alexei Dudnik, a Moscow-based historian told RBTH. “Badaber was set up as a center to provide relief to Afghan refugees, but the presence of military instructors from the CIA was a closely-guarded secret.”

Attempted prison break

The Soviet and Afghan prisoners, led by Victor Duhovchenko, took a few weeks to plan their escape. “They monitored the movements of their jailors, all of whom were ultra-religious,” says Dudnik. On the evening of April 26, 1985 less than a handful of the 72 prison guards were in the fortress, as the rest went to pray at a nearby mosque. “This was the moment that the prisoners were waiting for,” says Dudnik.

Knowing that the prison was almost empty of its guards, one group of Soviet troops led by Duhovchenko overpowered a guard that brought soup to the prisoners. This group then killed two guards at the fortress armory and seized weapons before freeing the prisoners.

“Their aim was to capture the radio tower and inform the Soviet army in Afghanistan of their whereabouts,” says Dudnik. The head guard managed to raise an alarm, setting up the stage for a fierce battle. Key positions in the fortress remained under the control of the prisoners.

The fortress was soon blockaded by Afghan Mujahideen, Pakistani infantry, tank units and artillery forces. Burhanuddin Rabbani, who would later become president of Afghanistan, initially tried to negotiate with the prisoners, who insisted that they be released. “Since Pakistan did not want to risk the wrath of the Soviet Union by even acknowledging the presence of the troops, they would have never agreed,” says Dudnik.

A pitched battle lasted well into the next day with the Soviet and Afghan troops offering fierce resistance, despite being heavily outnumbered. Some reports indicate that even Pakistani helicopters were involved in the operation, which ended when the fortress was totally destroyed by an explosion.

What caused the explosion remains unclear. Some reports indicated that the Pakistani Air Force accidentally bombed a military arms depot that contained more than two million modern rockets and weapons.

Were there survivors?

All the prisoners were believed to have been killed in the uprising, but doubts persist.

Given the secretive nature of the Soviet state, there was no official comment on the incident, says Dudnik. “There is a chance that a couple of Soviet soldiers escaped and managed to reach Afghanistan,” he says.

Russkaya Semyorka magazine cited a 1985 U.S. State Department memo as saying: “The humanitarian camp area of approximately one square mile was buried under a dense layer of fragments of shells, rockets and mines, as well as human remains. The explosion was so powerful that locals were coming across the fragments at a distance of 4 miles from the camp, where 14 Russian paratroopers were kept, two of whom survived the uprising’s crushing.”

Russian estimates put the toll of the enemy as up to 120 Afghan Mujahideen, 90 Pakistani soliders and six foreign instructors.

The Pakistani government, headed by Gen Muhammad Zia-Ul-Haq, tried to stop Pakistani publications from writing about the incident, but The Muslim newspaper wrote about the uprising and it was used by the mainstream Pakistani press.

“This was the only incident of direct combat between Russia and Pakistan,” Dudnik says.

Russian retaliation

The Russkaya Semyorka report mentions strong reprisals by the Soviet Union.

“In 1987, as a result of the Soviet raids into Pakistan, 234 Mujahideen and Pakistani soldiers were killed,” the magazine wrote. “On April 10, 1988 a powerful explosion occurred in the ammunition depot at Camp Odzhhri, located between Islamabad and Rawalpindi, leading to the death of between 1,000 and 1,300 people. Investigators concluded that it was a diversion.”

Dudnik says that many analysts in the Pakistani defense establishment even blame the USSR for the plane crash that killed Zia-Ul-Haq.

Although Russia-Pakistan ties have warmed over the last few years, the uprising is far from forgotten. “It is enough to recall the rebellion of Russian prisoners of war in Peshawar, which was brutally suppressed by Pakistani forces,” Former Russian Ambassador to India Vyacheslav Trubnikov told Russia Direct last month. “This memory still remains but we need to look at things from a wider perspective now.”

Russian veterans and military historians still seek further information on the uprising. “We have gained information that one of the participants of those events lives in the United States. And we asked Americans to specify how we can get in touch with him, retired Maj. Gen. Alexander Kirilin, secretary of the Russian Military Historical Society's academic board told RIA Novosti in June 2016.

“Films like the 9th Company displayed the heroics of Russian troops in Afghanistan. The Badaber Uprising is another act of bravery that the Russian public should know about,” Dudnik says.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox