The treasures of Troy in Moscow's Pushkin Museum.

Lori/Legion-MediaInside a small room in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Art, an exhibit of gold jewelry, stone axes and bowls is on display. The objects are all part of what is known as “Priam’s Treasure,” the spoils of the ancient city of Troy. The items were discovered during excavation works in what is now Turkey at the end of the 19th century. Originally given to the city of Berlin by German entrepreneur Heinrich Schliemann, how the treasure ended up in Moscow is a story of plunder, war and legal wrangling.

Schliemann's career began in the office of the import/export firm B. H. Schröder & Co in the Netherlands. Soon, however, his outstanding talent for foreign languages earned him a promotion: he was sent as the company's representative to Russia. He was based first in St. Petersburg, and later in Moscow. Schliemann was granted Russian citizenship in 1846; in 1852, he married Yekaterina Lyzhina, the daughter of a well-to-do Russian merchant. Schliemann did not settle permanently in Russia, though. He traveled extensively and eventually divorced his wife, in part by taking up residence in Indiana.

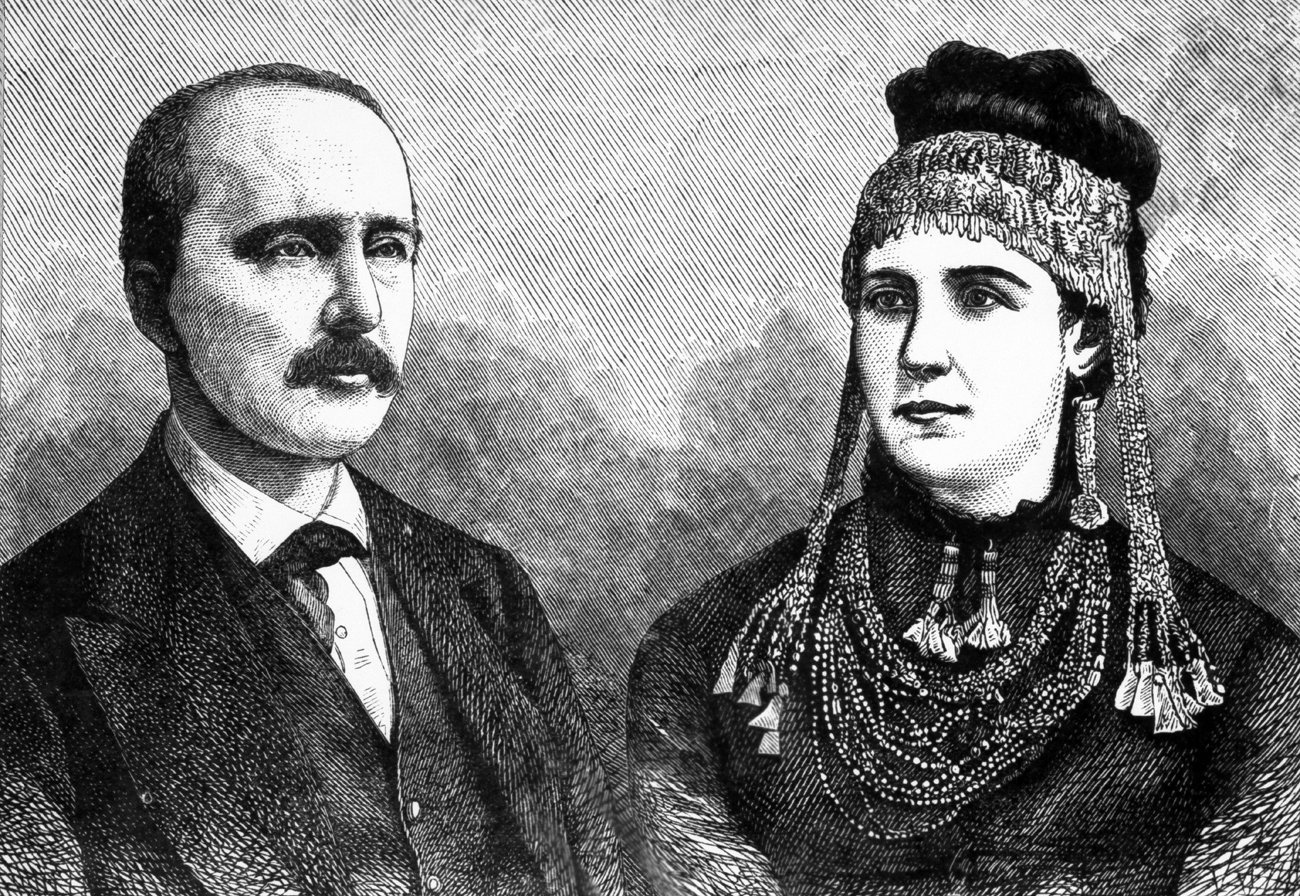

Dr. Heinrich Schliemann with his wife. / Source: Getty Images

Dr. Heinrich Schliemann with his wife. / Source: Getty Images

By 1858, Schliemann was wealthy enough to retire and decided to devote himself to finding the ancient city of Troy. In 1873, during excavation works on a hill called Hissarlik in what is now Turkey, he found his first treasure. “The discovery of Priam's Treasure was an international sensation,” said Vladimir Tolstikov, chief curator of the collection at the Pushkin Museum and director of the museum's department of art and archeology of the ancient world.

Schliemann continued with his archaeological work almost until his death in 1890. According to different estimates, he found between 19 and 21 treasures. The collection was held at the Royal Museums of Berlin until the onset of World War II.

During the war, the treasures were first kept in the basement of a Berlin bank. When aerial bombardments began, the items were moved to an air-raid bunker. In April 1945, as Soviet troops were storming Berlin, the collection remained under constant care of Wilhelm Unverzagt, a Berlin museum director. According to Tolstikov, Unverzagt, feared that the collection might be destroyed and voluntarily surrendered the crates containing the treasure to Soviet soldiers in July 1945. They were then taken to Moscow.

Source: Lori/Legion-Media

Source: Lori/Legion-Media

After the war, the Germans began searching for the collection, but its whereabouts were unknown until 1994. “Only two people in the world knew where it was: the director of the Pushkin Museum and the collection curator,” Tolstikov said.

Priam's Treasure might have remained classified for much longer had it not been for Grigory Kozlov, an employee of Russia’s Culture Ministry, who had access to archives and service correspondence. In the 1990s, Kozlov published information about the treasure in the U.S. press. After the information was made public, Russian Culture Minister Yevgeny Sidorov ordered the collection to go on display. In 1995, experts from Germany and other countries were invited to inspect the collection and sign a document certifying its authenticity. An exhibition of the collection was staged in 1996.

At this point, Germany filed a formal protest demanding that the collection be returned. In 1998, the Russian parliament reacted by adopting a law on cultural objects that had been taken by the Soviet Union World War II and were currently on Russian territory. The document declared all such objects “the federally owned property of Russia.”

“The law came into force, no one is going to breach it,” said Tolstikov. “Our German colleagues understood that they would not be able to do anything about it, so now we cooperate successfully and organize joint exhibitions.”

Vladimir Tolstikov / Source: Nadezhda Serezhkina

Vladimir Tolstikov / Source: Nadezhda Serezhkina

Alexandra Skuratova, an assistant professor in the international law department at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), agreed that there is no point in the German government protesting the law.

“This is a legal result, and it has legal implications,” Skuratova said. She added that Priam's Treasure may be viewed as partial compensation for the destruction of Soviet cultural objects during the war. According to official statistical data, more than 160 Soviet museums and 4,000 libraries were damaged during the war, and 115,000 books were destroyed.

Skuratova also notes that the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict was adopted in 1954, after World War II. As per the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, international treaties are not retroactive “unless the treaty otherwise provides.” The parties to the Hague Convention are not known to have expressed their intention to make the document retroactive, so it cannot be applied to the Priam's Treasure case.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox