The Smolny Institute for Noble Maidens was the first women's educational institution in Russia and paved the way for women’s education in the country. The institute was founded at the urging of Ivan Betskoy and in accordance with a decree signed by Catherine the Great on May 5 (April 24 according to Julian calendar) 1764. // The institute’s exterior

Archive Photo

Smolny Institute admitted the daughters of officials with a rank no lower than colonel or actual state counselor and paid for their education using funds from the state treasury. The daughters of hereditary nobles were also admitted for an annual tuition fee. The girls were prepared for life in the royal court and high society. // Teachers

Archive Photo

The institute’s curriculum included lessons on classic school subjects: Russian language, mathematics, history, geography, as well as music, dance, painting, sculpting, blazonry, etiquette, various means of housekeeping, religious studies, and others. // Dance lessons

Archive Photo

Ivan Betskoy wrote the institute’s charter, instilling in it his pedagogical views that had been influenced by Western European Enlightenment philosophy, views that Catherine the Great also shared. // Music lesson

Archive Photo

The charter contained full regulations about the institute’s activity: rules on discipline, studies, and prayers; nutrition and uniforms, holiday assemblies, the positions of the head mistress and regent, a provision of caregivers, and an outline of how its four senators should be. // A medical examination

Archive Photo

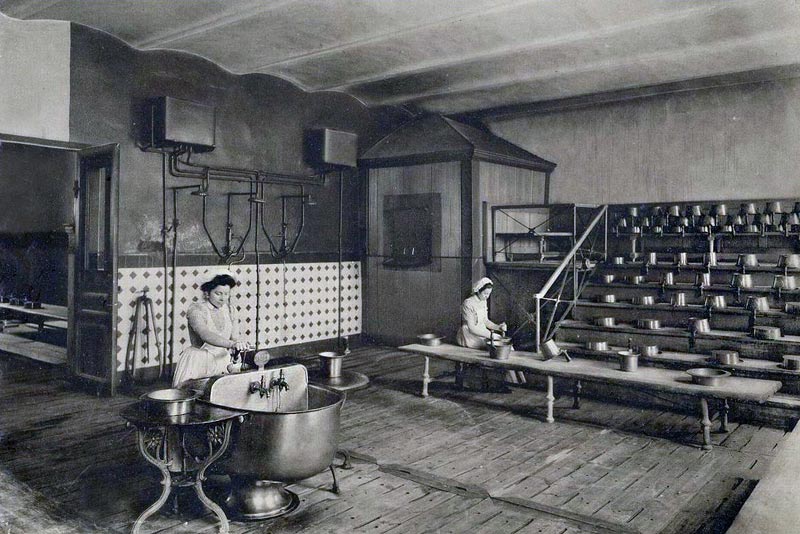

Girls aged from 4 to 6 years-old were admitted to the institute. Studies lasted 12 years and were broken up into 4 age groups of 3 years each. The admission of the first group of 4- to 6-year-old girls took place in August 1764. // In the wash room

Archive Photo

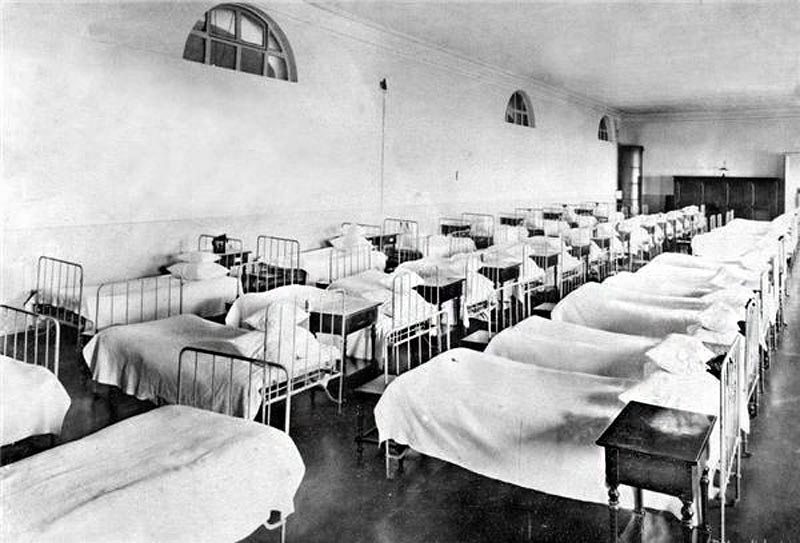

Initially, the pupils started their studies at the age of 6 and finished at 18. Later, the study period was reduced to 9 years (start from 9 years-old). Life at the institute was unique for its simplicity and austerity. // A dormitory

Archive Photo

Older pupils were assigned in turns to the youngest class in order to familiarize themselves with methods of upbringing and education in a practical context. Lessons were from 7 to 11 am and 12 to 2 pm. They alternated between physical education, daily walks, and games played outdoors or in classrooms. // Leisure time.

Archive Photo

The institute’s pupils has to were special dresses of a specific color as part of their uniforms. The youngest children wore a coffee-colored uniform; the second class, dark blue; the third class, light blue; and the older pupils were white (legend has it that Catherine the Great designed the dresses herself). // Sewing class

Archive Photo

Their diet was simple and nutritious and consisted primarily of meat and vegetables. They only drank milk and water. // Lunch

Archive Photo

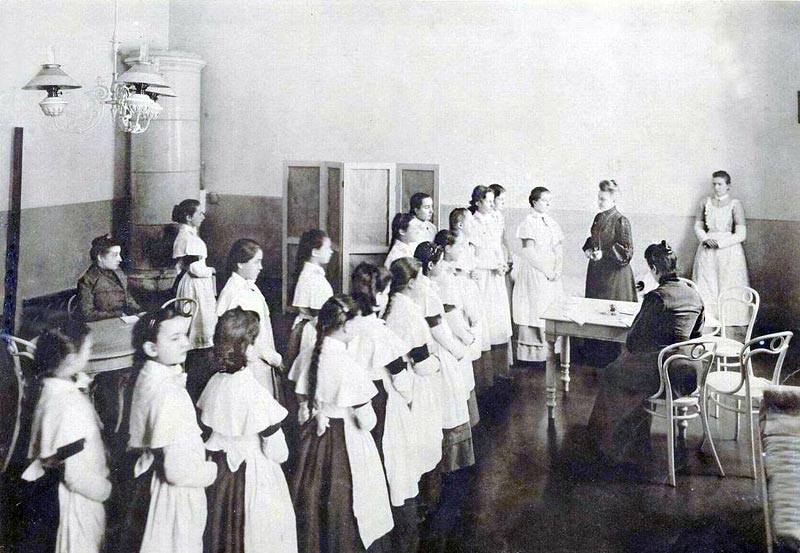

Students studied all year-round. There was no vacation. Exams were held three times per year. // An admissions exam on knowledge of good etiquette

Archive Photo

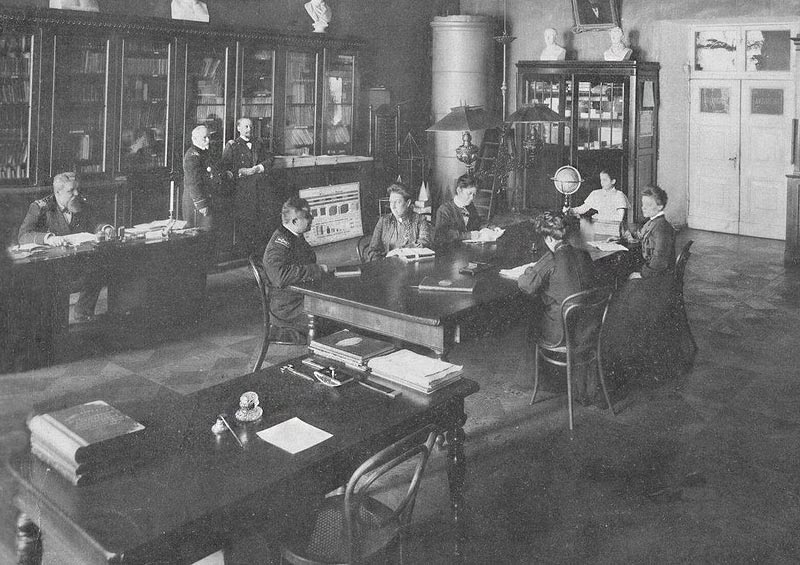

The heads of the classes had to treat their pupils with prudence and humility. They were ordered to avoid punishments, opting instead for “admonishing” the guilty parties. According to the institute’s first charter, parents could only visit their daughters on assigned says and with the head mistress’ permission. The school was intended to completely replace their family. // The teachers’ room

Archive Photo

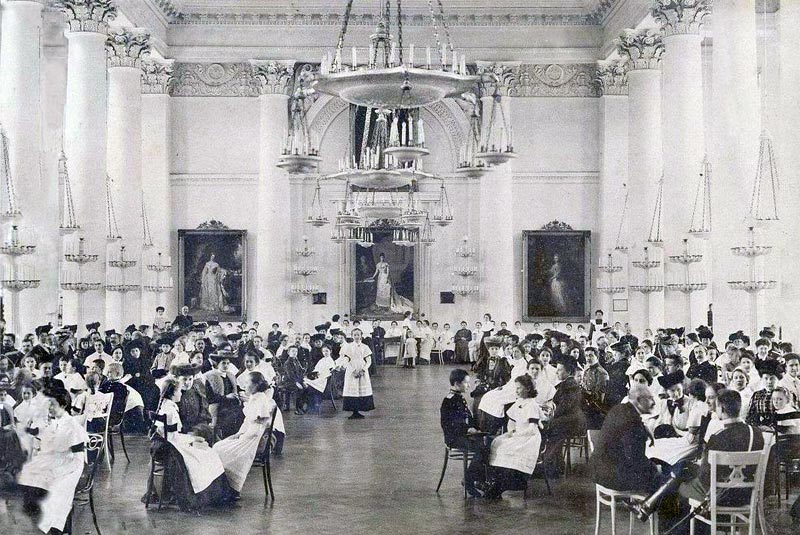

The regular tuition for girls’ food and board was 300 rubles per year. However, the tuition for certain students was significantly higher. The additional funds were used to educate poorer students. More than half of the girls studied thanks to funds provided by benefactors. The empress’ boarders sewed green while the boarders of individuals sewed ribbons to be worn around the neck in a color of the benefactor’s choice. // Music lesson

Archive Photo

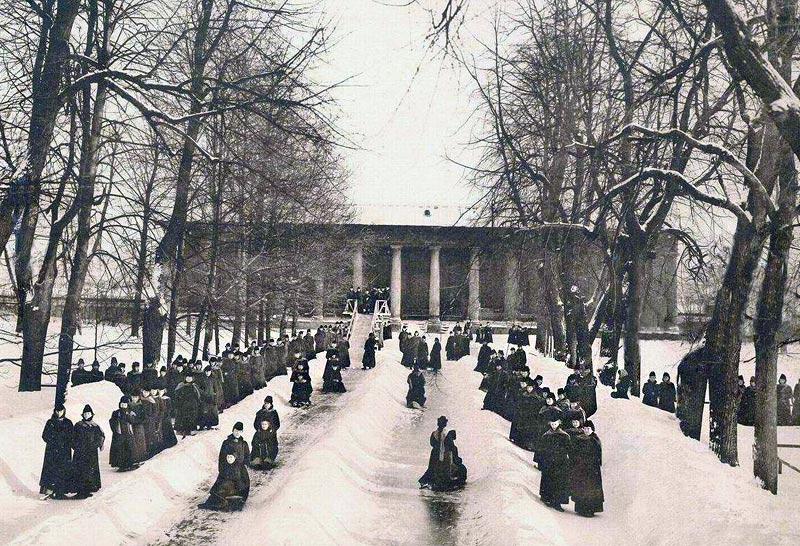

Changes were introduced to the students’ lives in 1859, when the prominent pedagogue Konstantin Dmitrievich Ushinsky was appointed the institute’s inspector. He made changes to the school’s curriculum and, most importantly, instituted vacation since raising young girls apart from their families negatively affected their lives later on down the road. // Sledding from a hill

Archive Photo

During the Communist Revolution of 1917, when the Bolshevik committee set up headquarters in Smolny, the interior of the White Hall underwent some changes, although not immediately. Vladimir Lenin’s first speech in October 1917 took place in the White Hall, with its previous interior. // Physical education lesson

Archive Photo

The remaining students were remarkably lucky, at least by revolutionary standards, since the institute’s students, under the leadership of Grand Duchess Vera Golitsyna, were evacuated to Novocherkassk. There, in February 1919, the school’s last graduation was held. In the summer of the same year, the teachers and remaining students fled Russia with the White Army and the institute was reestablished in Serbia. // Graduating class of 1889

Archive PhotoAll rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox