'Sagaan Sag' on Olkhon Island

Olkhon Island is a sacred place for Buddhists and shamans. It’s always sunny here, and there are only 30 cloudy days a year: from mid-December to mid-January. During this time Baikal slowly but surely starts to freeze over; but the ice is not yet strong enough for vehicles, making the island off-limits to tourists. Baikal is enveloped in thick fog, temporarily screening Olkhon and its inhabitants from the outside world.

In the emptiness of this snow-covered island, man becomes a small part of a larger world. The days merge endlessly into each other, as local folk while away the time on domestic matters.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

Every winter morning Viktor rises at 7 am, heats the stove and gets busy around the house.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

An old-timer now, he’s used to an austere lifestyle and refuses to be cared for by relatives.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

Viktor used to fish aboard ships belonging to the local fish factory, but it was closed down.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

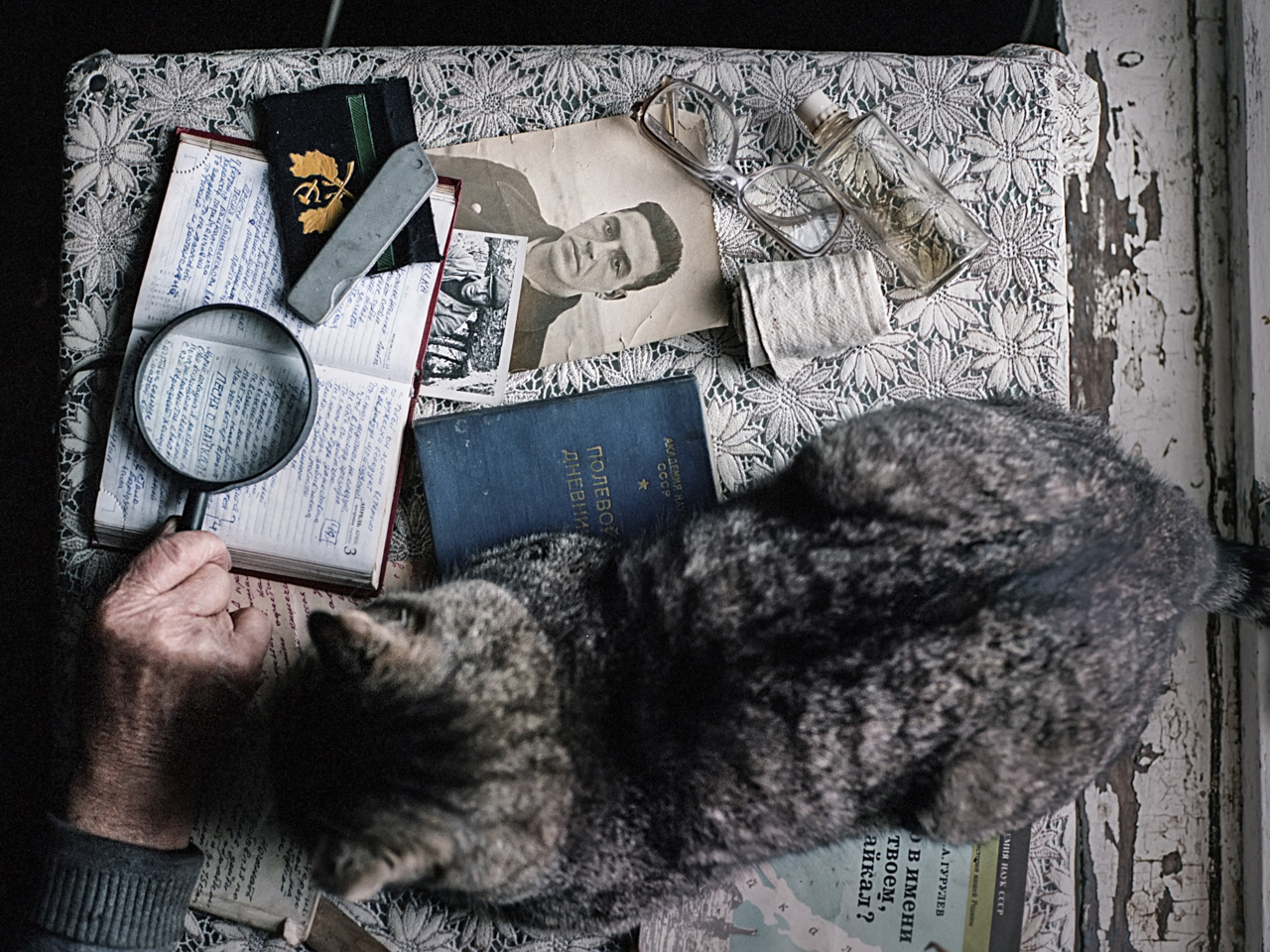

Viktor lives with a cat called Vasily, who lends a paw in everything, especially when it comes to reading and writing letters to friends.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

Viktor makes wine from Siberian berries and birch sap.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

There’s no plumbing on Olkhon Island, so until the freeze-over locals take their cattle to Lake Baikal to drink. At other times water is brought from the water carrier.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

The strong winds on the shore of Olkhon Island have bent many pines over backwards. Locals call them “walking” trees.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

Strolling along Cape Burkhan, you might come across sergyes—ritual poles with ribbons and offerings to the spirits. Cape Burkhan is considered the earthly palace of Chief Tengri (the overlord of Olkhon). It culminates with the “two-legged” Shamanic rock, which houses a sacred cave. The renowned Russian academic Vladimir Obruchev, who studied Baikal, wrote: “... most remarkable of all is the superstitious fear that Olkhon Buryats have of the cave. It is not allowed to pass by the Shamanic rock on wheels—only on horseback or in a sleigh, which is why in summer travel between the western and eastern parts of Olkhon is strictly on horseback, and only then on rare occasions, because Buryats are generally reluctant to go past the cave. Moreover, if there has been a death in the family, all kin, i.e. half the island, are forbidden from passing by the cave for a certain period of time. For this reason, my guide—a Buryat from Dolon-Argun—brought me to Khuzhir and went back. I passed by the cave with another baptized Buryat to the settlement of Kharantsy, where I found another guide; it was the same on the way back.”

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

One of the Olkhon airport buildings. In summer the island can be reached from Irkutsk by private small aircraft. In Soviet times such flights were weekly.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

In summer, maritime navigation on the Maly Sea (part of Lake Baikal separated from Olkhon island) is regulated by a series of lighthouses. Baikal experiences major storms. For example, in late September 1902 the ship Alexander Nevsky was badly damaged on the Maly Sea, wrecking the barges being towed, aboard which fishermen and their families were returning after the fishing season.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

A memorial to a drowned young man. Because it's a Buryat grave, offerings have been left.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

The skeletal hulls of fishing vessels that once belonged to the local fish factory. It opened in 1932, but today barely operates.

Elena Anosova

Elena Anosova

The island is home to a local Cossack community, which peacefully coexists with the Buryats. The island is generally tolerant of all religions: Buddhism, shamanism and Christianity.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox