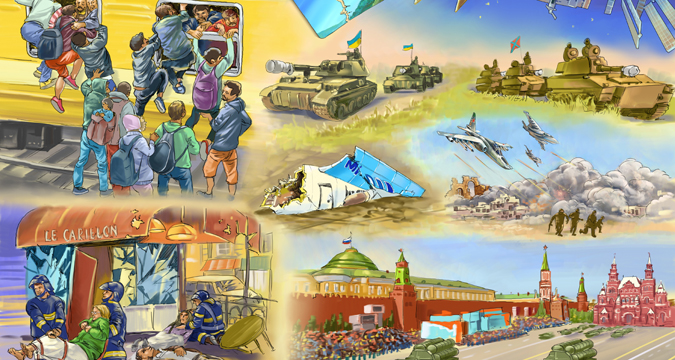

The world in 2015: A nostalgia for balance

Drawing by Dmitry Divin

The year 2015 is the first in which no-one is contesting the obvious anymore: that the world system is in a severe imbalance, one which keeps generating new crises. Many realized this a long time ago, but were reluctant to admit it, i.e. to give up the cozy perception dating back to the late 20th century that everything is going well and inevitable relapses can be successfully contained.

For example, Russia's actions to incorporate Crimea and support the anti-Maidan movements in eastern Ukraine were viewed as one such relapse. The leading powers (in terms of their impact on the world order, i.e. the West) tried – through consolidated political, economic and psychological pressure – to make the Kremlin change its behavior and return "to the right side of history.” In other words, they proceeded from the premise that the notion of "as it should be" exists.

The pressure on Russia failed to produce the desired effect, and then came the final turning point. In the case with Syria, no-one knows anymore what this "as it should be" is. The Middle East of 2015 has come to represent despair: The more effort is made, the more obvious it is that, first, such effort is ineffective, and second, that it is impossible in principle to rally the participants in this multi-layered conflict around a single goal.

ISIS: seeking to reset the game

The trend of the year is the hopeless desire to return to "the golden age,” with each player having their own idea of this. The most striking example is, of course, the main troublemaker of the Middle East region, which is now customarily referred to as Daesh (known in the West as Islamic State, or ISIS). Here, everything is straightforward: back to the caliphate, when everything was fair and square; down with the achievements of the so-called "civilization" that colonizers forced on the true believers.

The certain popularity that radical Islamists from what was once called Mesopotamia enjoy in the West, the interest in their ideas and actions is a sign that even outside of the proposed "caliphate" people feel an emptiness inside and increasingly long for something different from what they have now.

Having said that, it is not only the self-proclaimed caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS, who hankers after a golden past. Those who belong to mainstream global politics look back into the past for inspiration too – albeit a not-so-distant past.

A yearning for a more stable era

The memorable dates of the year 2015 are a reminder of historical events linked to the establishment of a particular world order: the 200th anniversary of the Congress of Vienna, the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II and the establishment of the UN, the 40th anniversary of the Helsinki Final Act, the 25th anniversary of the Charter of Paris for a New Europe.

Up to the end of the 20th century, the notion of a world order was always about balance. A complex balance, involving numerous players, as was the case in the 19th century. Or a relatively simple balance, as after World War II, when there emerged a system of equal dominance of two superpowers. A balance inevitably envisaged a mutual recognition of spheres of influence in one form or another. That was the foundation for the Vienna model, the Yalta system, the Helsinki Final Act.

At first glance, it may seem that the 1990 Paris Charter, which declared an end to spheres of influence and division lines, is based on a different principle. However, in practice, it too required a balance, not for confrontation but for rapprochement. In effect, this is what Mikhail Gorbachev dreamt of: As far as he was concerned, the end of the Cold War should have been based on a convergence, an equal and mutual coming together of previously competing blocs. The break-up of the Soviet Union shut the door on that option: Russia was not perceived as a second center in Europe.

Irrespective of what is being declared officially, an ideal for Russia would be a return to some form of agreed spheres of influence. Hence the nostalgia for Vienna and Yalta. The ideal for the West is the situation of the 1990s, when the spheres are no more and the influence has become universal. Hence the constant references to Helsinki (omitting, however, to mention that component of the Helsinki Accords that established the very same spheres of interest) and Paris, which envisages a commonality.

A proliferation of global actors

Neither of these nostalgia-inducing models can be brought back. What makes today’s politics different from the era of “world orders” is how uncommonly democratic it is. There are too many of those who are influencing the processes now.

Now the list consists of not just the major powers, as before, but also of numerous mid-range countries seeking to make it into the international premier league, interstate organizations with their bureaucratic inertia, huge corporations (with communications giants being in a league of their own), non-state actors, like non-governmental organizations (ISIS, in effect is one of them) and even some individuals who possess intellectual power over other people.

Inside states too, decision-making is made more complicated by the fact that governments are unable to fully control what is happening on their territory: It is impossible to fence oneself off from the numerous influences of a global world.

Clearly defined spheres of interest are out of the question. Those who used to belong to them in the past are no longer prepared to accept this type of relations, while those who used to control them do not have enough levers of power to force anyone.

The outgoing year has shown that the dominant trend is not the universality of a pyramid-like world, as it seemed in the 1990s, but the fragmentation of the world into more manageable segments. They operate according to their own rather than universal rules. The Trans-Pacific Partnership set up in October this year is a prototype of this type of a “bloc.” Another component should be the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, which U.S. President Barack Obama hopes to reach an agreement on before the end of his presidential term.

A balance of two oceans

The year 2015 has not only become a Rubicon marking the start of something new, it has also shown that it is impossible to bring back the past. The authors of the Valdai Club annual report, which this year is called “War and Peace in the 21st Century,” are convinced that “the rise in chaos and unmanageability in international relations cannot last forever … most likely, we are witnessing the emergence of a new structure of the world, based on what is effectively a balance, albeit loose, of two large groups of states.”

“Now, a new order will not be reborn on the post-war ruins of the previous order but will gradually ‘germinate’ from a dialectic chaos of rivalry and interdependence,” reads the report. This is happening organically, irrespective of the will of the main players, who are still captivated by the past.

A flexible balance of "the two oceans" with America in the center on the one side, and the continental mass of Eurasia with a close partnership between China and Russia on the other, is at first glance somewhat disconcerting. It looks too much like yet another version of the classic geopolitics of the Mahan and Mackinder variety or like the grim predictions of George Orwell with his Eurasia and Oceania.

In fact, these are two communities that are united by common interests from within but are interdependent and not confrontational to each other, at least not always. This is the best option that one can imagine today. Yet another version of an “end of history”-inflected “eternal peace,” predictably, has turned out to be a utopia.

The author is the editor in chief of the Russia in Global Politics magazine and head of research at the Valdai International Discussion Club.

The opinion of the writer may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

Subscribe and get RBTH best stories every Wednesday

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox