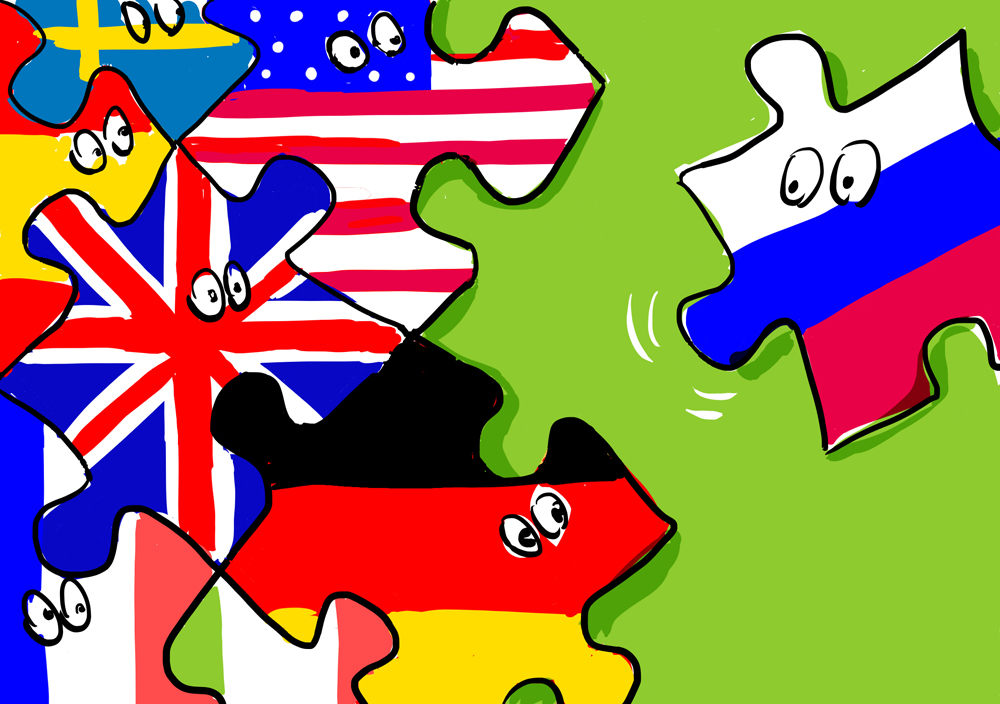

Will Russia integrate into the Western world, post-sanctions?

Drawing by Iorsh

The news of President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker's decision to come to the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum and meet Russian President Vladimir Putin, as well as a series of calming statements made by German politicians (Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel and Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier) have engendered a wave of discussions on the fate of the sanctions against Moscow and Russia's relations with the West.

However, the main question concerns not when and how the sanctions will be lifted, but what will follow.

Patterns in relations with the U.S. and the EU

With the United States it is simple. Relations develop according to one pattern: from cooling/tension/escalation to thaw/détente/reset and back. The degree of one period or another varies, but the algorithm does not.

But presently the relations are not going through a typical moment. By all appearances, they are in the "bad" phase. However, due to the specific character of the current American president, who simply prefers to avoid conflict, containment is rather blurry.

After the change in the White House the relations will either become very clear (Clinton) or they will temporarily cool off (Trump). However, the general cycle will not change. Separate atmospheric fluctuations are possible but it is not easy to change the accumulated inertia of reciprocal baiting and repulsion.

The situation with continental Europe is more interesting. The EU and Russia agree that it is impossible to return to the "business as usual" model, that is, the "strategic partnership" of the 1990s-2000s. This model does not lead to anything because no one knows what "unusual business" is, and even if there are ideas, they are practically diametric.

Cutting off relations is not a possibility – this is the second and final common position.

From the 1990s until recently, relations, especially since the end of the 2000s, despite some deviations, were based on the presupposition that Russia would eventually integrate into "the European sphere," whose administrative and directive center is in Brussels.

"Greater Europe," in turn, was a regional branch of "The Greater West," which was the nucleus of the world order. Despite the impediments that became clear in the beginning of the 21st century, by the middle of the 2000s the following "cosmogony" formed on a conceptual level.

The West (consisting of the U.S., with its allies in the Pacific Ocean, and the EU, with its own swath of states longing to join it) holds all those countries that institutionally are not part of Western structures but depend on them on a leash.

The U.S. was in a condition of close economic symbiosis with China – hence the idea of a "Chimerica," whose political dimension would have resulted in a G2.

Meanwhile, the EU was creating "common space" with Russia, which would have stretched the regulatory framework from Lisbon to Vladivostok. Thus, the northern hemisphere appeared well developed and efforts could have been made to curb risks from the south.

A failure at the very heart

The financial crisis in the U.S. and the structural problems in the EU that it partly brought about have cast doubt on the West's ability to dominate effectively. This has led to, on the one side (the non-Western), the aspirations of countries to diversify their "relations portfolio" and on the other (the Western), the desire to prove its might.

In the middle of the 2010s another reality was born. Under political tensions, economic interdependency transformed from a way of containing contradictions to a weapon of influencing the vis-à-vis.

This shook up what was already a fragile balance within the former order. It also spurred the ambitions of those, who like Russia, had never felt comfortable in the conditions that the West was offering.

The leading Western powers' approach changed from external expansion to "concentration on earnings" and consolidation of positions, to strengthening the habitat delineated over the last 25 years. Such a trend can be seen in the U.S. and in the EU, but on different levels.

Washington intends to solder its allies together with large-scale economic and legal partnerships: the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TTP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Brussels is concerned with stabilizing the EU and is concentrating on internal problems.

The U.S. and the EU's objectives may clash. For example, the White House's insistence on concluding the TTIP before the end of Obama's presidency is creating nervousness in the EU by virtue of the talks' secretive and opaque nature.

Where does Russia fit in?

The description of the new "architecture" has a direct relationship to the subject of "life after sanctions," since it raises the question of where will Russia fit in. However, the idea of fitting in raises great doubts in itself.

As stated in the recent reports published by the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy, "the course towards unconditional integration into the global economy, which Russia has been on since 1991, has exhausted itself primarily because the economy itself is changing radically."

Global space is not being divided into isolated segments and the general interdependency is irremovable. But, judging by what is happening, those who wish to become a part of the traditional Western nucleus will have to accept harsh conditions with minimum bargaining power. The previous stage of globalization had an element of altruism: The countries that were diligently catching up were given a chance to find their own place.

Now the objective is different: to have the "grandees" fully responsible for all the development possibilities.

And what choice do the others have? Either to create something of their own that is capable of competing with the Western community, or build a complex and flexible network of relations with the most diverse subjects in order to scrape up opportunities everywhere possible.

Greater Eurasia

In Russia's case the first option is a Greater Eurasia, the integration of projects from the Eurasian Union and China's Silk Road, the latter which was announced in May 2015 but which has not yet progressed far. The option should not be considered dead since the continuation of the West's policy is objectively pushing Moscow and Beijing towards something similar.

The second choice is a maximum multi-vector approach, ultra-pragmatism. This definitely requires the reduction of geopolitical tensions, not for Russia to fit into the Western project, but more likely for it to use the project's internal contradictions more effectively for its interests.

There is potential for this. Not everyone is enthusiastic about the abovementioned Western "consolidation" scheme because it limits their room for maneuver with China, Russia or anyone else.

Asia is full of such examples: Japan is doing everything possible to develop relations with Russia without abandoning its solidarity with the United States. Southeast Asian countries are uncomfortable with Obama's rhetoric, which transforms their participation in the TTP into an anti-China act.

Many would prefer something similar to an open marriage instead of the rigid fixation on mega-bloc obligations: The partners would guarantee each other loyalty but not full-fledged fidelity.

The unity and contrast of these approaches is likely to become the main substance of the next stage of building the world order. And the subject of lifting the sanctions against Russia is secondary compared to how Russia should act faced with these developing processes.

First published in Russian in Gazeta.ru

The author is chairman of the Presidium of the Council on Foreign and Defence Policy.

The opinion of the writer may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox