Are the U.S. elections really a turning point for global geopolitics?

U.S. President Barack Obama meets NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington on May 31, 2013.

ReutersExactly 12 years ago, in the midst of the U.S. election campaign, a conference on international relations was taking place in New York. George Bush Jr. and John Kerry were in contention for the chair in the Oval Office. The campaign was taking place one and a half years after the United States’ invasion of Iraq and most of the event's participants were imploring the highest powers, and the voters, to liberate America from what they saw as the evil named Bush.

In the heat of the discussion a representative of one of the African countries stood up and said: "Since humanity is so dependent on who will be the U.S. president, why doesn’t the whole world then elect him?"

But the proposal did not result in laughter – it was met with approval. At the time Bush was very unpopular on the international stage and in the event of a "universal" vote he would have had no chance of winning. Unlike in his own country, where a month later he was voted into office for another four years.

A landmark election campaign

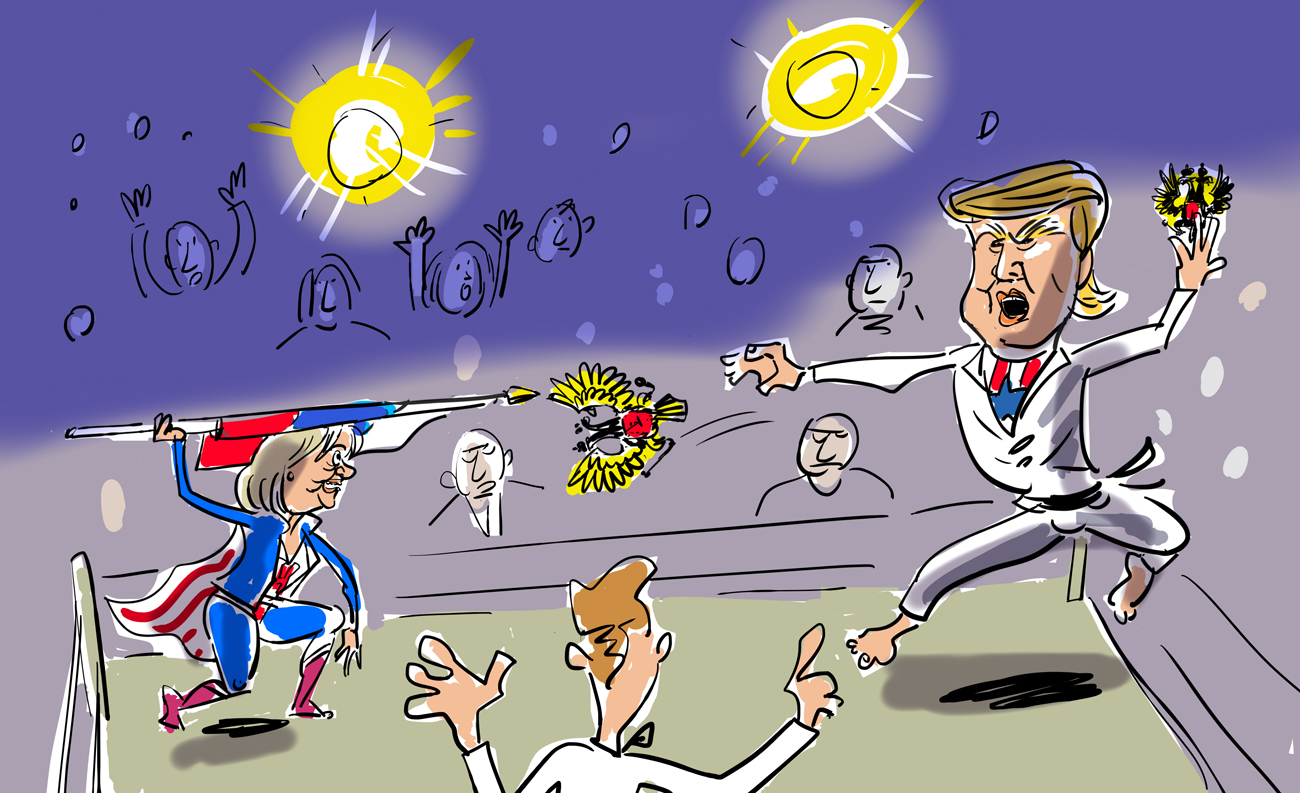

The raising of the question itself perfectly reflects the perception of the situation that was formed after the Cold War. Whichever candidate had won back then, and even if he was not appreciated, it was clear that he would become the most important politician in the world. Today all countries are again following the American presidential campaign, holding their breath. But for the first time in a quarter of a century the rivals noticeably differ in their understanding of the role that the United States should play in the world arena.

When various external players questioned the axiom of America's global leadership, it was considered one of the costs of the process of spreading democracy, which began a quarter of a century ago. But the emergence of numerous social layers in the West that do not understand why it is necessary to make so many efforts abroad when there are so many problems domestically has shaken some foundations.

That is why the current election campaign is unique. Obviously it is directed at the voter, but it is also directed at the foreign audience, which must be persuaded that America does not intend to renounce its global leadership. To be honest, however, a clear understanding of how that leadership must be pursued in the future is lacking.

Rasmussen’s call to action

This week an interesting controversy unfolded between U.S. President Barack Obama, who spoke before the UN General Assembly, and former NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen, who published an article in The Wall Street Journal.

Speaking at the UN is typical for Obama. He always emphasizes his country's special role, listing all its great contributions to humanity. But he constantly has reservations. He says that America is not omnipotent, that a unipolar world is not a norm but an exception and that the U.S. has made mistakes. Obama's duality and his search for a balanced approach show that he realizes more than any of his compatriots how multi-dimensional today's world is.

However, what is important for an academician rarely benefits a public politician.

Obama, who began as an embodiment of a new era, is constantly trying to lower people's expectations while at the same time being expected to present a position that is precise and that promises a clear result. In the end everyone is unhappy – not only his opponents who accuse the prudent head of state of weakness and evasiveness, but also his supporters who think that he has done too little.

Rasmussen, on the other hand, understands everything, like any ideological neoconservative. Threats are increasing, the terrorists are getting stronger, Russia is becoming more audacious, China is vying for global power – someone must put an end to all this.

"The world needs such a policeman if freedom and prosperity are to prevail against the forces of oppression, and the only capable, reliable and desirable candidate for the position is the United States." The Dane is calling on America to wake up. There is no need to analyze Rasmussen’s article seriously – it is just a propaganda leaflet addressed to the voter.

It would, however, be difficult to refrain from making one comment. Among the problems that require America's involvement in the name of preserving order and putting out fires (“a firefighter to put out the flames of conflict”), Rasmussen states that "In North Africa, Libya has collapsed and become a breeding ground for terrorists." I do not know who advised the former NATO secretary general to use this example, but if we consider the real history of the "fire" in Libya, the statement appears unfathomably cynical.

The times they are a-changin’

Obama and Rasmussen do agree on one thing: It is important that the U.S. does not adopt an isolationist approach. Consequently, they both support Hillary Clinton. Meanwhile, Obama, who speaks of people who have lost confidence in the future, is trying to woo potential Trump voters and have them see that the establishment understands their anxieties.

Rasmussen's drumroll, on the other hand, is addressed to those who do not need to be persuaded – their support just needs to be strengthened. However, it is possible that things are much more serious: The shift in the social-political paradigm that is clearly taking place in America and in the whole world means that the ruling class will also splinter.

The fatefulness of the upcoming elections is most likely exaggerated. Whoever wins will not break the system. Hillary will not be able to return to the 1990s for which she yearns or Trump to his beloved 1950s.

The inertia of the government machine is great, despite its confusion before the unpredictable reaction of the masses. But a gradual transition to a different phase is inevitable. It began with Obama, who tried to combine traditional slogans with a different policy. It will continue with the next president and will likely obtain a new form in the 2020s. But only if Obama's successor does not go out of his way to prove to Rasmussen that America is no longer asleep.

Fyodor Lukyanov is editor-in-chief of Russia in Global Affairs magazine and chairman of the Presidium of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy, an independent Moscow-based think tank.

First published in Russian by Gazeta.ru

Read more: Pacific pushback: How the Russia-China semi-alliance could stabilise Asia>>>

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox