Bathhouse worker dips herbs in a large pot of hot bathwater.

APOne of St. Petersburg's most popular bathhouses is located on Vasilevsky Island, on the 17th Line (many streets on the island have numbers instead of names). Here a visit to a real Russian banya with a large steam room and a massive stove that passes through all the floors of the building costs about as much as a ride on a city bus.

The women's section has more than 60 lockers for clothes, a mild-mannered bathhouse attendant, massage and pedicure rooms, as well as a jungle of potted flowers. The only man on the floor is a masseur. On weekdays, to wash here for a half hour costs 45 rubles ($0.69) or 20 ($0.3) on Tuesday, which is a discount day. Birch and oak switches, or veniki, can be bought here. Some go here to steam and some – from the nearby communal apartments, where there are no bathtubs – simply to wash themselves.

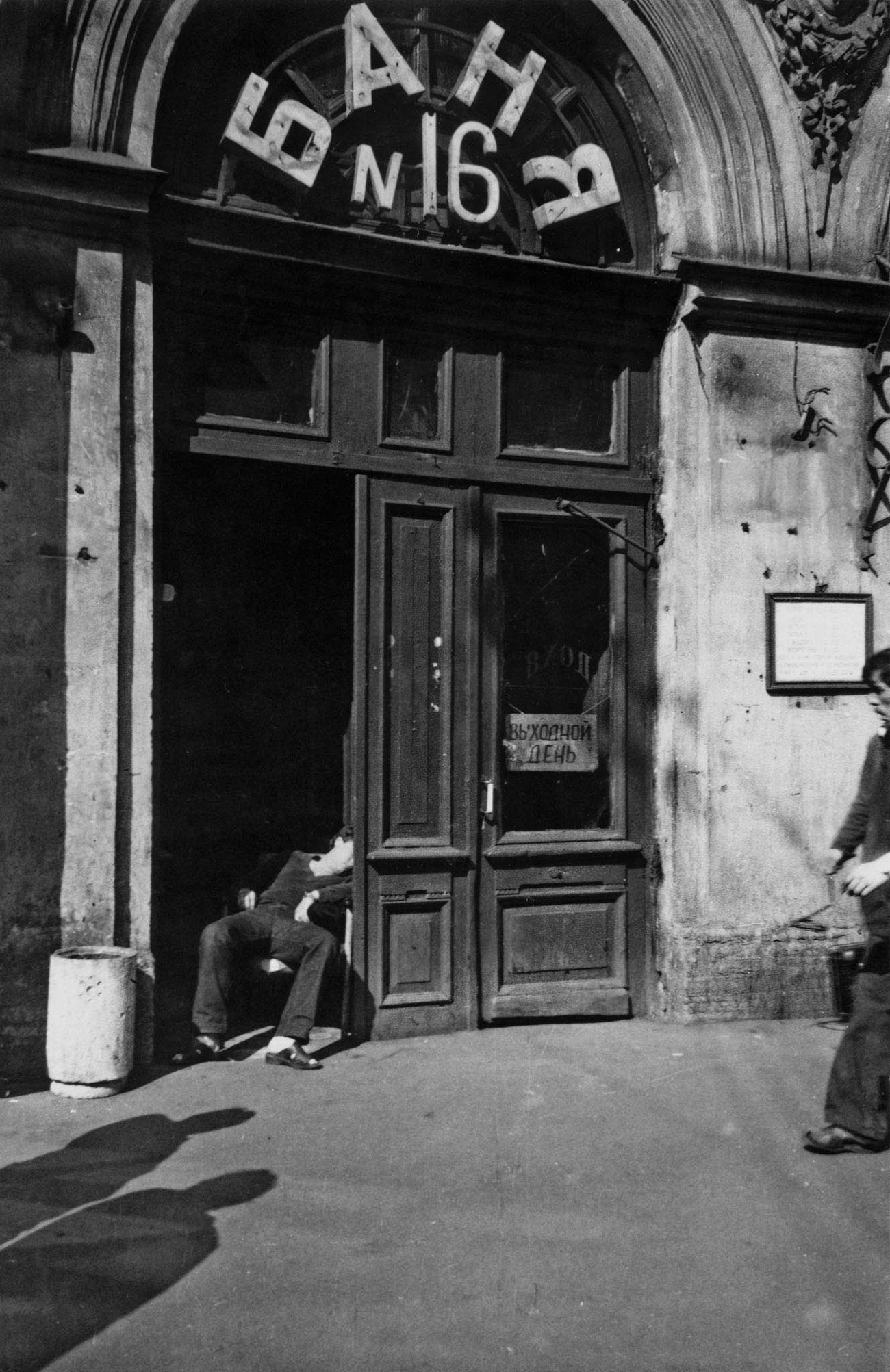

A public banya #16 in Leningrad, 1977. / PhotoXPress

A public banya #16 in Leningrad, 1977. / PhotoXPress

In the steam room, each of 40 to 60 women observes the unwritten laws: They are silent, so as not to "eat up" the steam generated by one of them who pours water on hot stones, and do not start to beat themselves with their venik until the steam settles. A very old woman with a cane climbs the damp wooden staircase. Every step is difficult for her. When upstairs, she blissfully inhales the steam and says: "Daughter, steam my back, or I won't make it home.”

A public banya in St. Petersburg. / Nadezhda Gorodetskaya/PhotoXPress

A public banya in St. Petersburg. / Nadezhda Gorodetskaya/PhotoXPress

This banya is considered to be the last of the budget bathhouses on the densely populated Vasilyevsky Island. A few years ago, the Gavanskiye bathhouse was closed, and since then, the visitors of this banya are clearly divided into former Gavankiye ones and local old-timers. A little closer to the city center, on the 4th Line, there is a bathhouse which is even older, and, one might even say, more famous.

Today, the bathhouse on the corner of the 4th Line is adorned with the sign "Imbir" ("Ginger"). Once upon a time, back in the 19th century, the building was built specifically as a bathhouse. For 167 years, people have steamed, washed themselves and relaxed their souls here. There were seven sections here, including a special one for mothers with children.

After steaming, as expected, in the women's section, I go, on the advice of the bathroom assistant, to the men's – according to her, it is there that the bathhouse's regulars congregate. I gently knock at the entrance to the men's corridor. The attendant, the masseur and even the visitors have all known each other for 20 to 30 years. They all remember that in the "freewheeling 1990s," the bathhouses were a place for gatherings of local crime bosses.

"Some used to fly out of the windows here," says visitor Vladimir. "All these thugs came here, and just sat in the steam room – with their gold chains and crosses. But they did not stage serious showdowns – after all, the banya was sacred for them. In 1994, there were 27 contract killings on Vasilyevsky Island. Just on the island! I know this, because I worked in the local police at that time."

However, the bathhouse on the 4th Line is famous not because of gangsters. It was here that famous Russian director Alexei Balabanov took a steam bath every week. It was also here that the famous "bathhouse" scene from Brother, a film with almost cult status in Russia, was shot. (The 1997 film tells the story of a demobilized Chechen war veteran who comes to visit his brother in St. Petersburg and is faced with the Russian reality of the time – crime, drugs, etc.)

Still photos from the film are on display in the lobby. "Yes, I knew Lyosha well," says local masseur Igor, who has worked in the bathhouse for 30 years. "He loved a good steaming. Now his son Pyotr comes sometimes, and, earlier, the entire management of Lenfilm [a major Soviet film company] would come here. Because people come here in groups, and each group is assigned a day of the week. For example, when the bathhouse on Gavanskaya [Street] was closed, the men from there began to come to us on Thursdays."

The city authorities passed this bathhouse, as many others, into private hands in the 1990s. Only those whose management is on good terms with the authorities continue to receive budget funding from the city government. The bathhouse's staff admits that it is generally running at a loss, but people need to be able to steam and wash on the cheap.

"Here, on Vasilyevsky, there are still lots of communal apartments, where there are no bathtubs," Igor continues. "But you can't wash in any bathtub as clean as in a banya. It strengthens the health of both body and mind, as they say. I guess you can say that the banya is a ritual. In the banya, everybody is equal, you know? In the 1990s, I fixed the backs of all the local crime bosses, and then of the entire local police department and people from the FSB [the successor to the KGB – RBTH]. And no one did anything to me, because I'm a good professional and just gave them a good massage."

A public bathhouse in St. Petersburg. / Irina Kuznetsova/PhotoXPress

A public bathhouse in St. Petersburg. / Irina Kuznetsova/PhotoXPress

But at a cost of 600 rubles ($9.22) not everyone can afford to regularly go to steam in Imbir, while the bathhouse on the 17th Line is packed on discount days. Many go to the cheap and simple Chkalovskiye bathhouse on the Petrograd Side, the neighboring island.

In the evening on a weekday, I go there, too. This is one of the few remaining municipal steam houses in St. Petersburg. The massive building with columns is built in the post-war Empire style, with two wings. A Finnish sauna or a Russian banya? The sauna costs 35 rubles, the banya is 45.

I go to the banya. "People come for different things here," says banya attendant Yelena, in the women's section. "Some out of habit, some for health. For example, there is one old woman, she’s already 98 years old. It is hard for her to walk, and she certainly cannot steam for health reasons. But once a month, she comes and washes herself. But when you offer, for example, to help her get dressed, she always refuses. She says, "Rub my back, and I’ll manage with the rest, little by little."

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox