Distinguishing faces: What do Russians think about migrants?

In the course of many years, Russia has been second only to the U.S. in terms of numbers of foreigners coming to the country.

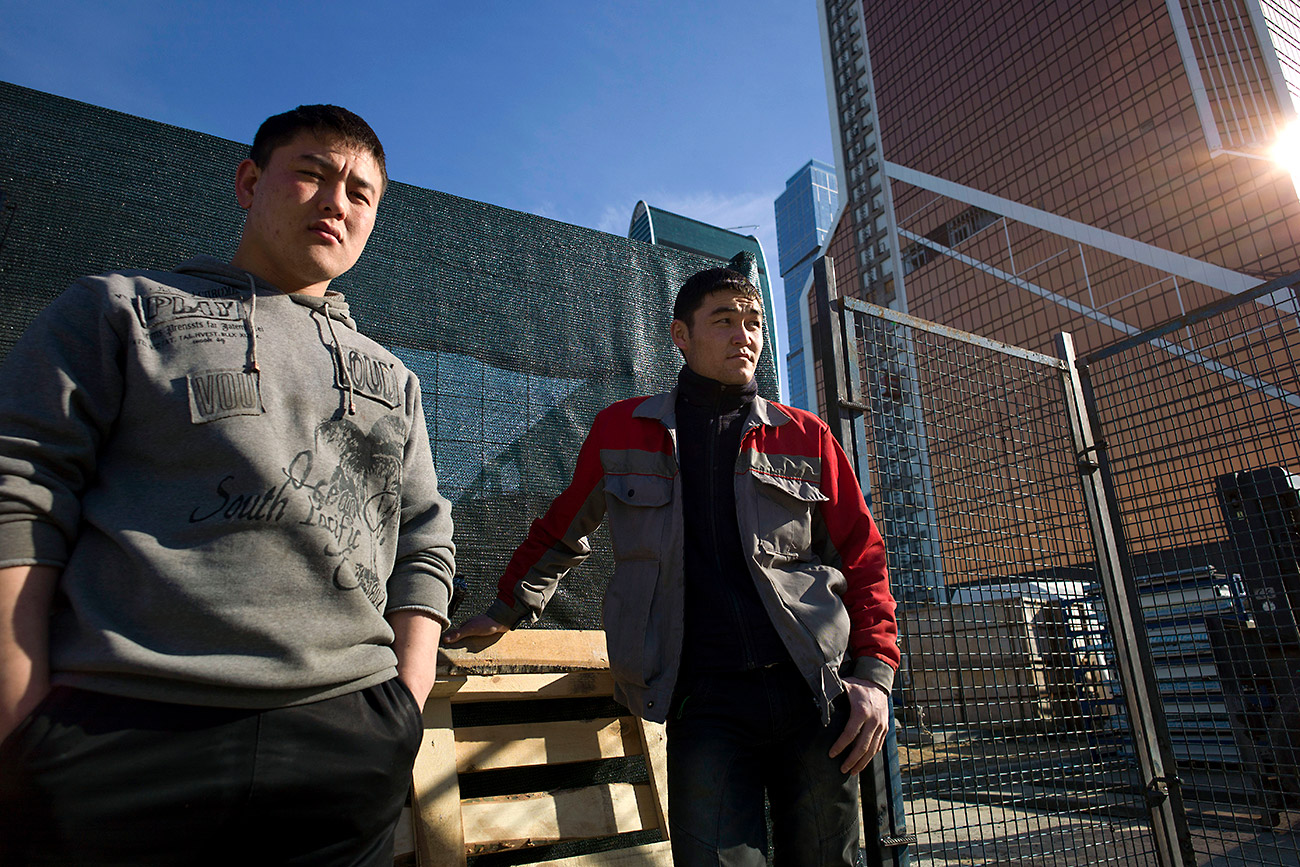

Getty ImagesOver the last 20 years Russian cities have accepted more and more migrants. Last year alone, 16 million people entered the country, 12 million of whom are from Central Asia (the figure equals that of Moscow's population). Today, many of them work in construction, subways, shopping centers, and roads. Many work at the city's main construction sites and often 80 meters below ground. Many also staff shopping networks and clearing companies.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, people from Asia now make up the fifth migration wave in Russia after Ukrainians, Azerbaijanis, Moldovans and Armenians. In the course of many years Russia has been second only to the U.S. in terms of numbers of foreigners coming to the country. However, 67 percent of Russians regard migrant workers as an invasion from the poor East that must be stopped, according to the Levada Center sociological research organization. Sociologists believe that intolerance to newcomers is not a trend but an established attitude in Russia, and neither immigration reform nor the tolerance centers have been able to influence Russians. But often other factors are to blame for this.

Passengers of the Tashkent to Moscow train at the Kazansky Railway Station in Moscow. / Photo: Alexey Filippov/RIA Novosti

Passengers of the Tashkent to Moscow train at the Kazansky Railway Station in Moscow. / Photo: Alexey Filippov/RIA Novosti

Migrants as part of policy

Russians are also generally intolerant to non-Slavic Russians from the North Caucasus. Actually, the percentage of Russians who have a negative attitude toward them is higher (41 against 38 percent). And in the last few years intolerance has been increasing towards Ukrainians, while positive attitudes have grown towards migrants from Transcaucasia. "Ukraine - bad, Georgia - good" fully illustrates Russia's relations with these countries, believes Levada sociologist Karina Pipiya. "We see how international political events, such as the conflict with Ukraine, have influenced attitudes towards migrant workers from Ukraine," she told RBTH. With respect to Georgia, Russia is showing a more favorable disposition and this has produced its effects.

In this photo taken on April 30, 2015, a Tajik migrant municipal worker caries Russian national and Moscow city flags to decorate the State Department Store, GUM, behind Red Square in Moscow. / Photo: AP

In this photo taken on April 30, 2015, a Tajik migrant municipal worker caries Russian national and Moscow city flags to decorate the State Department Store, GUM, behind Red Square in Moscow. / Photo: AP

The subject of migrants has a significant impact on domestic policy. "Politicians are no fools. They use the migrant factor for their benefit and play on popular moods," notes the sociologist.

During the 2013 election campaign, a visa regime with Central Asian countries was one of the foremost policy points on oppositionist Alexey Navalny's agenda. The unsystematic politician did not become Moscow's mayor but came in second place, receiving 27 percent of the vote (Sergei Sobyanin won with 51 percent). Xenophobic moods in society at the time were strong and several months later poured out into protests in Moscow's Zapadnoye Biryulevo district with pogroms and clashes with police (there was a vegetable base in the district that employed mostly migrants). The mass media reported that the protesters were primarily ethnic. As a result, this year sociologists have recorded the highest level of aversion towards migrants since 2002: 78 percent.

Create your own infographics

In 2018, Russia will hold a presidential elections and it’s possible that negative attitudes towards migrants will only increase. Pipiya believes that this topic will be raised again. Russian President Vladimir Putin has traditionally protected migrants: He has instructed officials to develop a law for migrants' adaptation and declared amnesty for those who illegally extended their stay (giving them a possibility to enter Russia anew). However, he also introduced additional registration fees and called on officials to fully ascertain the purpose and the period of the migrants' stay in Russia. "We need to solve the issue of foreigners who entered Russia without a visa and have been in Russia for a long time without a concrete purpose. Or so they say… But probably they do have a purpose. The government just doesn't know about it."

A man puts on a mask after a protest in the Biryulevo district of Moscow, Oct. 13, 2013. / Photo: Reuters

A man puts on a mask after a protest in the Biryulevo district of Moscow, Oct. 13, 2013. / Photo: Reuters

Scandalously famous Russian parliamentarian and leader of the LDPR, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, proposes to deal with migrants using half measures: Deporting them only from the megacities and distributing them among the regions, which need a labor force. Leader of Russia's unsystematic opposition Alexei Navalny proposes a more radical solution. "I’m for Central Asia, I just want there to be a visa regime. This is a normal honest measure," tweeted Navalny, who was the first in the country to begin an unofficial presidential election campaign and "work visas for migrants" is again one of the points on his program. But Navalny's participation in the elections is now in doubt.

A worker stands at the Luzhniki stadium, which is undergoing a major rebuild to be ready to host the 2018 World Cup final, in Moscow, on Sept. 7, 2016. / Photo: AP

A worker stands at the Luzhniki stadium, which is undergoing a major rebuild to be ready to host the 2018 World Cup final, in Moscow, on Sept. 7, 2016. / Photo: AP

The phantom millions

The protests in Biryulevo, the crisis of Syrian refugees in Europe, the officially insane nanny from Uzbekistan who cut off a child's head - each incident or tragedy involving migrants creates an upsurge in negative attitudes and phobias. "ISIS is changing residence: Terrorist migrants are coming from Central Asia." This was a headline that the state-owned NTV TV channel used after the terrorist act in the St. Petersburg metro on April 3, 2017. "All the places where migrants work, especially the so-called outsourcing, clearing companies, the construction sites and others are at risk. Several years ago the Petersburg metro fired local cleaners and hired migrants, and who can distinguish their faces?" Russian citizens began writing. And only more compelling news, such as Crimea's unification with Russia, can neutralize these phobias.

In this photo taken on April 22, 2015, migrants wait to be interviewed at the Moscow center for registration for migrant workers in Sakharovo village out Moscow, April 22, 2015. / Photo: AP

In this photo taken on April 22, 2015, migrants wait to be interviewed at the Moscow center for registration for migrant workers in Sakharovo village out Moscow, April 22, 2015. / Photo: AP

The 2014 migration reform, which forced migrants to obtain (rather expensive) work licenses and which aimed to legalize the market and increase the local population's tolerance to the work force from visa-free countries, did not influence public opinion. It substantially reduced the number of migrants (according to the Russian Statistics Service, with respect to certain nationalities, the decrease was up to 40 percent), but surveys showed that Russians did not even notice this.

A migrant waits to be interviewed at the Moscow center for registration for migrant workers in Sakharovo village out Moscow. / Photo: AP

A migrant waits to be interviewed at the Moscow center for registration for migrant workers in Sakharovo village out Moscow. / Photo: AP

"The share of those who say that the figure decreased is insignificant. Focus groups affirm that they know the practice of issuing licenses, but this is not enough. In 2016, 78 percent of Russians favored the idea of introducing a strict visa regime. This means that the reform went through but the people did not start thinking that there were less migrants and that they were better treated," says the Levada Center.

A foreign worker smokes during a raid conducted by the Federal Migration Service to identify illegal migrants in Moscow. / Photo: Valeriy Melnikov/RIA Novosti

A foreign worker smokes during a raid conducted by the Federal Migration Service to identify illegal migrants in Moscow. / Photo: Valeriy Melnikov/RIA Novosti

The economic crisis played a big role. It increases irritability. In modern Russia a Tajik is synonymous with a low-paid illegal immigrant who is ready to work in very bad conditions. Meanwhile, Russians will not want to work in such places for such money. "And yet, Russians still believe that migrants are taking their jobs, just because the level of confidence in the future is low," Pipiya explains.

Foreign workers detained during a raid conducted by the Federal Migration Service to identify illegal migrants in Moscow. / Photo: Valeriy Melnikov/RIA Novosti

Foreign workers detained during a raid conducted by the Federal Migration Service to identify illegal migrants in Moscow. / Photo: Valeriy Melnikov/RIA Novosti

But if we disregard the possessive attitude towards work places (the demand for migrant workers is indeed high), Russians are mostly irritated by the migrants' low education level and capability only to perform unqualified labor (32 percent of respondents), as well as the cultural, social, and language barrier. "They smile, but this doesn't mean anything," "they almost never show their real feelings," "they think one thing, say another, and do something else and there is always a fourth element," "they don't understand what people tell them," "they don't know how to behave," "they behave as if they were at home" - these are the most frequent complaints about migrants and they usually engender hostility among Russians, rather than compassion or understanding.

Read more: Moscow uses controversial fairy tales to integrate migrants into society

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox