Several countercultures coexisted in the 1980s.

Anastasiya KaragodinaCounterculture in the Soviet Union, a country cut off from the West by the infamous Iron Curtain, consisted of an “open youth rebellion against ideological and cultural stagnation,” writes Misha Buster, author of Hooligans of the 80s. His book is one of several reputable sources that records stories of people who lived in the final days of the USSR. It also has a unique collection of personal photos.

Stilyagi (a derogatory appellation for members of a youth counterculture), hippies, rockers, punks, and metalheads coexisted until the end of the 1980s although each group experienced varying degrees of popularity during different periods.

Each group had a popular meeting point. Attraktsiya, a spot on Moscow’s Arbat Street was a magnet for breakdancers, while Zheltok Restaurant on Chistye Prudy Square was popular with hippies. Countercultural groups often fought each other, but sometimes united against policemen, who would later arrest them.

The Soviet media called them “non-conformists,” who deliberately devoid of all the good qualities possessed by a diligent Soviet citizen. They were even referred to as lazy parasites and fascists.

Many people interviewed in Buster’s book said many members of counterculture groups moved abroad, while some managed to start a business or a get a ‘normal’ job.

The term Stilyagi, often translated as hipsters, dandies or beatniks, is the name of the first counterculture group from the Soviet Union. Born in the late 1940s, their heyday was in the 1960s, during the Khrushchev Thaw period, when censorship was relaxed (when compared with the Joseph Stalin era).

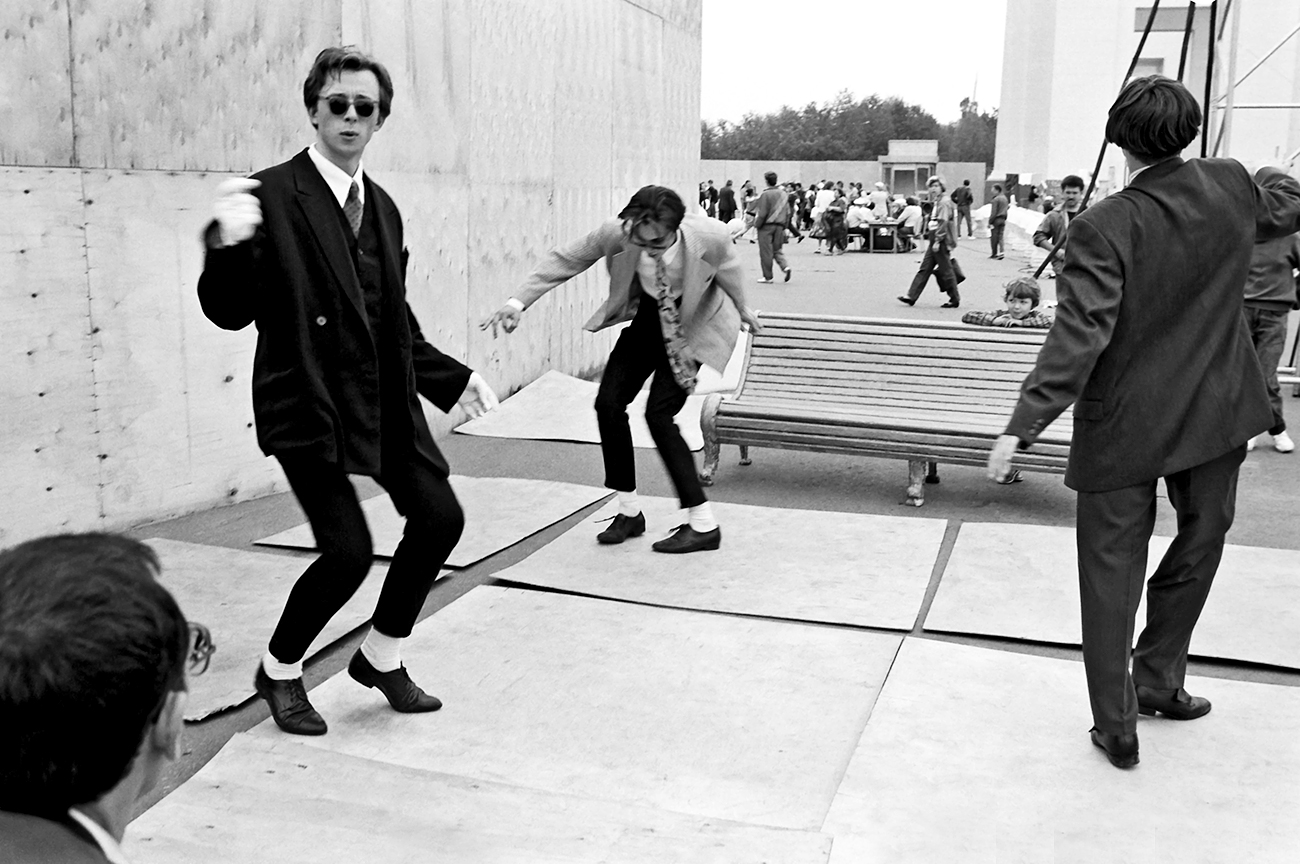

Moscow mods of the late 1950s dancing twist. / Valeriy Shustov/RIA Novosti

Moscow mods of the late 1950s dancing twist. / Valeriy Shustov/RIA Novosti

Having apolitical views and an admiration for foreign fashion, they tried to wear foreign labels and listen to western music. They greatly favored swing and boogie-woogie. Women wore dresses and high-heeled footwear, while men chose narrow checkered pants and shiny winkle-pickers.

Though their style changed a bit over time, the Stilyagi always wore unapologetically bold colors and bright jackets. Alexander Petlura says, “keeping footwear shiny was so important, that they had a habit of wiping the tips of their shoes on the back of their pants, which eventually grated the fabric.”

After the Soviet youth got acquainted with the Western world during the Khrushchev Thaw period, many other common subcultures became popular in the country, including hippies. On the surface, hippies in the USSR were quite similar to those in the United States. However American hippies mainly rebelled against consumerism, while their Soviet counterparts defied a conformist state, writes William Jay Risch in his book Soviet ‘Flower’ Children.

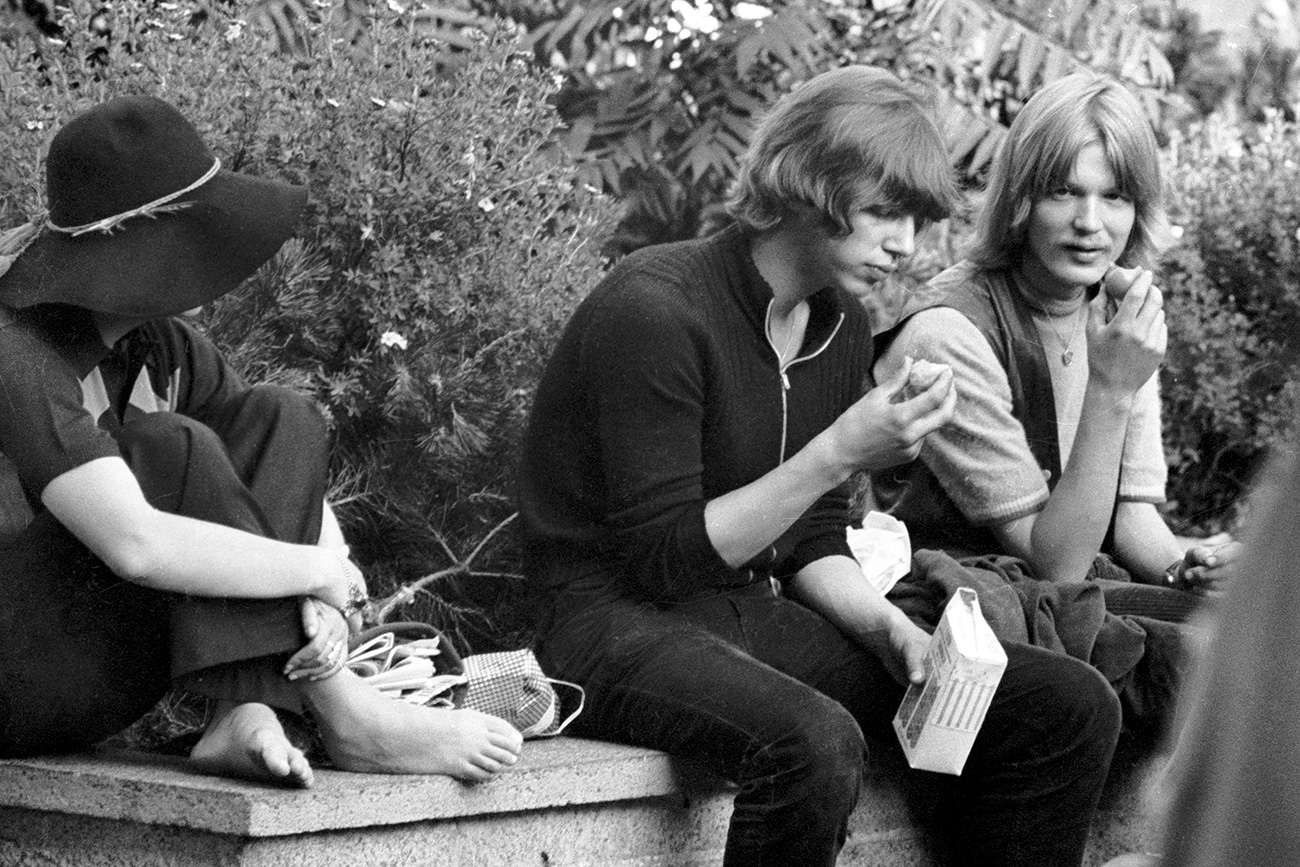

Hippies / Lev Nosov/RIA Novosti

Hippies / Lev Nosov/RIA Novosti

Soviet Hippies heavily used English slang and loanwords, and were heavily influenced by folklore. They often used to narrate their life stories, which were used as an alternative to anecdotes. The stories, called ‘telega (carts),’ were later compiled into a book called 1001 Party Telega by Stepan Pechkin.

Soviet hippies, who generally shrugged off the idea of working, chose to beg for a living, says Petlura. They preferred to imitate the dressing style of fellow hippies in the United States, he adds.

The biker counterculture, just like that of the hippies, was also adopted from the West. In the USSR, where people usually could not afford a car, bikes became a common substitution. However, only a miniscule minority of Soviet bikers actually owned a bike, adds Petlura.

A female biker sitting on a motorcycle. / Oleg Porokhovniko/TASS

A female biker sitting on a motorcycle. / Oleg Porokhovniko/TASS

Many of them called themselves rockers and the two terms were often interchanged.

They liked hard rock music, which was illegally distributed in the USSR. The bikers tried to imitate their Western counterparts, but the lack of real leather jackets in the Soviet Union forced them to improvise. Some bikers tried to sew their own leather jackets, while most wore fake leather. A few just used plain black fabric instead.

In Buster’s book, which consists of multiple interviews with important figures of the era, Feddy Begemot recalls that his “his first leather jacket was sewn by his sister Anya.” Bikers were also fond of paddings just like their associates abroad. While they liked Naval Jacks, skulls, crosses, and other symbols, they were very much against alcohol and drugs.

Despite having to penetrate the Iron Curtain, the breakdance movement was popular among the Soviet youth. Most of them learned the moves by themselves or by copying them from Western movies. Mila Maximova in an interview for Hooligans of the 80s remembers that many of them preferred to make arm waves and robotic moves, while just a few people actually managed to master spins or other power moves.

Breakdancer Performing in Gorky Park / Getty Images

Breakdancer Performing in Gorky Park / Getty Images

“We knew them by name, there were about five of them in Moscow,” she adds. By the time the breakdance movement gained massive popularity as a counterculture, the Soviet youth developed their own fashion style. “White sneakers and gloves were important,” says Maximova. It was close to impossible to find white sneakers since most pairs available in the market were brown or black. Breakdancers often bleached their shoes.

They also liked knickers that “did not look anything like jeans” and a lot of additional accessories such as chains, sweatbands, bracelets, and sweatshirts with foreign logos.

A special project dedicated to Soviet counterculture by Look at Me and Adidas Originals says the dancers later managed to get “skateboards and spray paint.”

With banned foreign music growing in popularity, alternative genres, including heavy metal, became a fad among young Soviet citizens. Heavy metal bands like Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, Metallica, Judas Priest, and Megadeth were popular among the rebellious youth.

The scene from "The Commentary on the Appeal for Pardon" movie directed by Inna Tumanyan. Metalheads / S. Ivanov/RIA Novosri

The scene from "The Commentary on the Appeal for Pardon" movie directed by Inna Tumanyan. Metalheads / S. Ivanov/RIA Novosri

Nikolay Korshunov wrote in an article for Russia’s Hooligans magazine that Soviet metalheads took their counterculture very seriously and would try and stop posers. Youngsters, dressed as metalheads, would be stopped on the streets and questioned about their knowledge of heavy metal. They would be asked to name at least 15 heavy metal bands. Many new fans would fail the test, Korshunov added.

Since getting a real leather jacket or jeans was close to impossible, many metalheads improvised.

“We couldn’t be bothered with wearing American clothes,” Sergei Okulyar says in Hooligans of the 80s. “We needed to have something of our own, which looked as intimidating as possible.”

Sometimes people would make sweatbands from handbags and then sell them to punks or other metalheads.

Punks were less uniform in their style, which mainly depended on which part of the USSR they lived in, Siberian punks were offshoots of hippies, while punks from Tallinn were indistinguishable from their European counterparts. St. Petersburg’s punks led a “half-Bohemian lifestyle,” and those in Moscow fused styles from across the country.

Punks in Moscow / Iliya Pitalev/RIA Novosti

Punks in Moscow / Iliya Pitalev/RIA Novosti

The inner nihilism was in contrast with their outer appearance, which comprised of brightly colored Mohawks, piercings, jackets, T-shirts with images of their favorite bands, and handmade belts with rivets.

Misha Clash says in Hooligans of the 80s that their dress code changed to “long leather coats, heavy dark makeup and haversacks.”

Their performances often turned violent and ended with the smashing of the windows of major stores. This eventually led to arrests and detentions. There are also stories of loud punks coming to the civil registry office in an inebriated condition. It was a part of the punk culture to shout profanities while getting married.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox