The last Soviet terrorist: The man who tried to assassinate Gorbachev

Unlike with Victor Ilyin—another famous would-be-assassin who fired at Leonid Brezhnev and was also sent to forced treatment instead of getting the death penalty—Shmonov's experience in the psychiatric facility took a heavy toll.

Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH Unlike with Victor Ilyin—another famous would-be-assassin who fired at Leonid Brezhnev and was also sent to forced treatment instead of getting the death penalty—Shmonov's experience in the psychiatric facility took a heavy toll. Source: Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH

Unlike with Victor Ilyin—another famous would-be-assassin who fired at Leonid Brezhnev and was also sent to forced treatment instead of getting the death penalty—Shmonov's experience in the psychiatric facility took a heavy toll. Source: Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH

Alexander Shmonov is a very hospitable host. As I enter his home, he allows me to keep my jacket on and offers me some tea and cake, telling me to come in and sit wherever I like. However, there is nowhere to sit, as his entire studio apartment, including the one bed, is filled with boxes of rags. It is not entirely clear where Alexander sleeps or eats, given that even in the kitchen there is not a single empty spot.

In the end, I start speaking with Shmonov while still standing. "I've just moved in," he says, trying to justify the mess. He begins to tell me about his plans for the future, which are rather strange for a 64-year-old pensioner. "I sold the place I used to live a month ago and used the money to buy an apartment in a new building that’s still in the construction phase. That’s why, for the time being, I’m renting this place. As soon as they finish the building, I'll sell that apartment for much more than I bought it. I'll keep part of the money, and with the rest I'll hire three programmers who will bring my invention to life."

There is nowhere to sit, as his entire studio apartment, including the one bed, is filled with boxes of rags. It is not entirely clear where Alexander sleeps or eats, given that even in the kitchen there is not a single empty spot. Source: Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH

There is nowhere to sit, as his entire studio apartment, including the one bed, is filled with boxes of rags. It is not entirely clear where Alexander sleeps or eats, given that even in the kitchen there is not a single empty spot. Source: Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH

Shmonov has been working on the invention for several years and, casting modesty aside, refers to it as "a breakthrough," albeit one he has thus far been unsuccessful in patenting. Its official title is "Methods of invention with which three programmers can easily create software with which a computer can invent many inventions without the help of man."

Over the years, last would-be-assassin of the Soviet period has produced more than two dozen such inventions, all of which he tries to tell me about. There is "Method for increasing the average living standard of all Russian non-businessmen by two or three times within one year." And "Method to significantly reduce the number and degree of customer deceptions." Or "Method for improving citizens and creating copies of people for this." There is even "Method for improving a man's sexual potential without the use of medicine," which consists solely of the following explanation: "For improving a man's sexual capabilities, a man must always (that is day and night) keep his legs apart."

All of this testifies to the fact that, unlike with Victor Ilyin—another famous would-be-assassin who fired at Leonid Brezhnev and was also sent to forced treatment instead of getting the death penalty—Shmonov's experience in the psychiatric facility took a heavy toll.

Shmonov has been working on the invention for several years and, casting modesty aside, refers to it as "a breakthrough." Over the years, last would-be-assassin of the Soviet period has produced more than two dozen such inventions, all of which he tries to tell me about. Source: Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH

Shmonov has been working on the invention for several years and, casting modesty aside, refers to it as "a breakthrough." Over the years, last would-be-assassin of the Soviet period has produced more than two dozen such inventions, all of which he tries to tell me about. Source: Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH

Twins who did not know each other

In general, their stories are very similar. Just like Ilyin, Shmonov was born in Leningrad (currently St. Petersburg) and was a respectable Soviet citizen who studied at a construction-architectural technical school and worked as an engineer in a factory until he "saw the light." "In 1975, after Brezhnev signed the Helsinki Accords, the Soviet Union temporarily stopped blocking the BBC and Voice of America radio stations,” Alexander explains. “It was there that for the first time I heard the truth about what was going on in the USSR, about the persecution of dissidents. And I understood that the totalitarian regime was terrible."

Alexander Shmonov. / Source: Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH

Alexander Shmonov. / Source: Ruslan Shamukov/RBTH

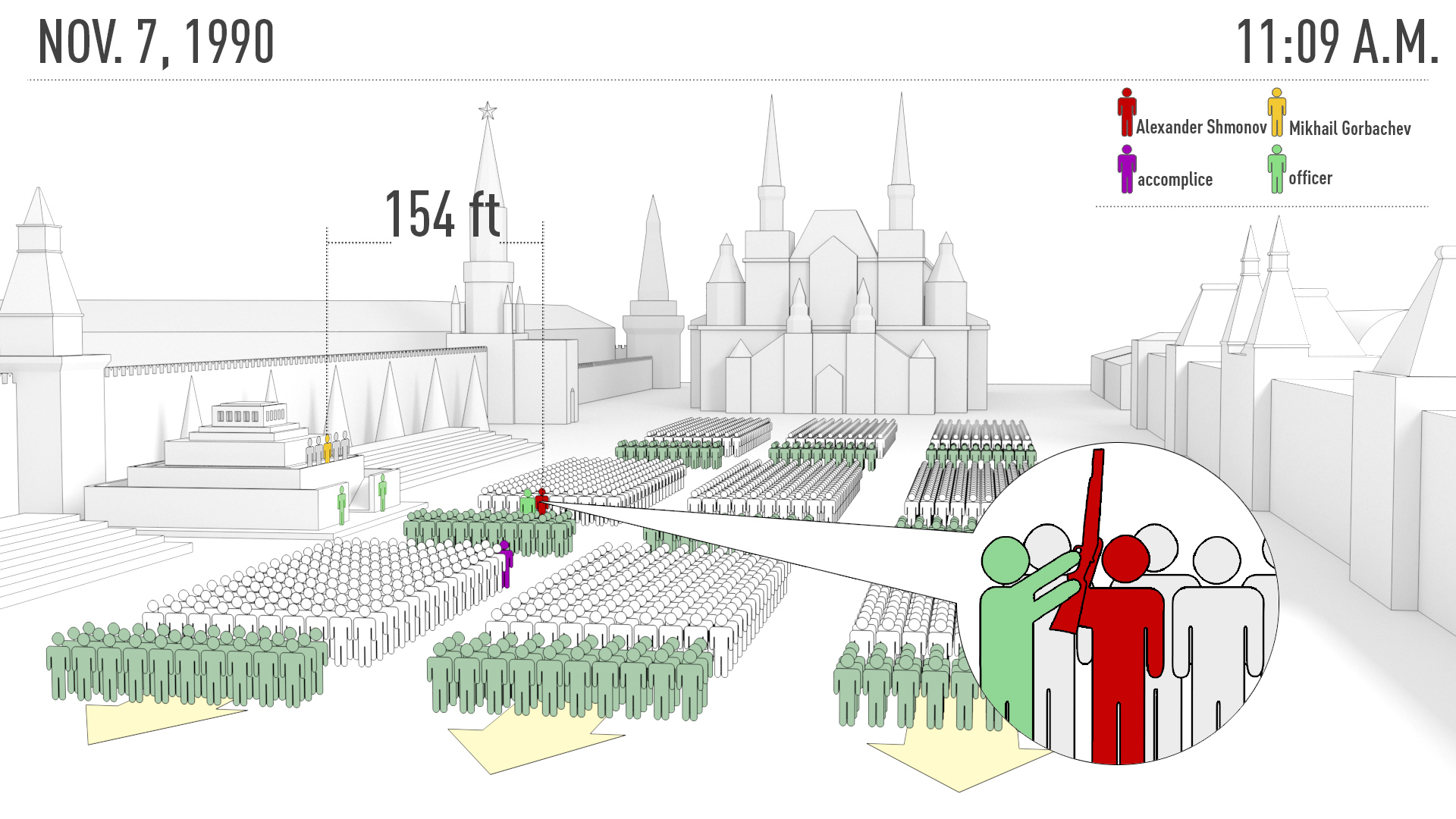

Just like Ilyin, Shmonov sent the Kremlin a letter with an ultimatum demanding direct nationwide presidential and parliamentary elections. And, just as with Ilyin, upon not receiving an answer, he decided to assassinate the leader of the Soviet Union. To implement his plan he went to Moscow for the festivities surrounding the 73rd anniversary of the October Revolution (which in the Gregorian calendar actually took place in November). The celebrations included a parade on Red Square and a salute from Gorbachev, who would mark the celebration standing on Vladimir Lenin’s mausoleum. "I told my wife I'd be at the dacha taking care of the garden, but in reality I got on the train and went to the capital," Alexander says.

I ask Alexander if he is acquainted with Ilyin. St. Petersburg is perhaps the only city in the world where two people who made assassinate attempts on a head of state live happily and peacefully. "No, we've never met, but of course I know his story," Shmonov tell me. He adds that there is one thing that distinguishes his assassination attempt from that of Ilyin: "I did not act alone. I had an accomplice."

Alexander Shmonov, center, during election campaign in Kolpino (Leningrad suburb), spring 1990. On the demonstration on red Red Square on Nov. 7, 1990. Source: M. Sharapov/RIA Novosti

Alexander Shmonov, center, during election campaign in Kolpino (Leningrad suburb), spring 1990. On the demonstration on red Red Square on Nov. 7, 1990. Source: M. Sharapov/RIA Novosti

Betrayed by a friend

Shmonov met his accomplice at a meeting of the Leningrad People's Front. In the beginning of the 1990s, the country went through a drastic decline in living standards. This was accompanied by reforms allowing for increased freedom of speech and media. As a result, a strong protest movement evolved during the final years of the USSR, with anti-Soviet demonstrations that drew hundreds of thousands of people taking place in Moscow and Leningrad.

This photo shows Alexander Shmonov (with a poster) in spring 1990 during the election campaign in Kolpino suburb of Leningrad. During the holiday demonstration on Red Square on Nov. 7, 1990 Shmonov fired a sawed-off shotgun at the Mausoleum. Source: M. Sharapov/RIA Novosti

This photo shows Alexander Shmonov (with a poster) in spring 1990 during the election campaign in Kolpino suburb of Leningrad. During the holiday demonstration on Red Square on Nov. 7, 1990 Shmonov fired a sawed-off shotgun at the Mausoleum. Source: M. Sharapov/RIA Novosti

The Leningrad People's Front was an unregistered social organization that consisted of around 2,000 members and demanded the democratization of the political system. Shmonov joined in 1989. In the spring of the following year he was approached at one of the meetings by a colleague who jokingly noted that, in the event of a revolution, he had a gun. "That is when I got the idea of an accomplice," Alexander says. "After all, it would be difficult to implement my plan alone."

Mikhail Gorbachev together with Boris Yeltsin during the military parade and demonstration, devoted to the 73rd anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution on Nov. 7, 1990. Source: Vladimir Musaelyan/TASS

Mikhail Gorbachev together with Boris Yeltsin during the military parade and demonstration, devoted to the 73rd anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution on Nov. 7, 1990. Source: Vladimir Musaelyan/TASS

It did not take long to convince Alexander's friend. Three weeks before the assassination attempt, Alexander bought a double-barreled hunting rifle. "We agreed that we'd both walk in the column of people at the parade, and when we got to the front of the mausoleum, I'd take out the rifle and take aim at Gorbachev. At that moment, so that no one would get in my way, my accomplice would take out another gun and demand that no one approach me or else he would open fire. But when the time came to do this, he panicked. At the last moment he just continued walking along with the column of people. I took out my rifle and was spotted immediately. While I was removing the safety catch and taking aim, an officer ran over and jerked the rifle by the barrel. That's why the bullets went past Gorbachev. Then the crowd jumped on me…"

Scheme of the assassination attempt at Gorbachev on Nov. 7, 1990. Source: Kirill Polukhin/RBTH

Scheme of the assassination attempt at Gorbachev on Nov. 7, 1990. Source: Kirill Polukhin/RBTH

I ask Shmonov whether he now considers Gorbachev a strange choice for a target. After all, it was Gorbachev who started Perestroika, opened the country’s borders and stopped censorship of the mass media. But Alexander remains adamant in his position. "He was directly involved in the deaths of people in Baku and Tbilisi. He did not follow in the direction of freedom that he himself had declared. In 1990, I was arrested three times for distributing flyers calling on people not to vote for members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.”

Three months without sleep

After the unsuccessful assassination attempt, Shmonov was taken to Lefortovo Prison. "I was there for a month," he recalls, "after which I was deemed insane and sent to the loony bin, although I was always conscious of my actions. They just didn't want to make a national hero out of me. So they declared me mad. And all this despite the fact that when I was buying the weapon I went through all the tests and received a certificate of mental health."

Surprisingly, Shmonov speaks calmly about the horrors he witnessed in the municipal psychiatric clinic. "The conditions were like in a concentration camp. There was absolutely no air to breathe. All the windows and fortochkas (small ventilation windows—RBTH) were boarded up. The place had not been aired out for years, and we were not allowed outside, although this right was guaranteed by law. I wrote to the prosecutor's office, complaining about the conditions. The head doctor found out, came into my room and told me directly: 'Well, hold onto yourself now. No more pills. Just heavy injections.' Do you know what Fluphenazine is? It's when, after the injection, you can’t stand, sit or lie down. Your body jerks around constantly. That injection lasts a month. Three months later I wrote my mother. ‘Do something, convince the doctor, give him a bribe, just get me out of here.’ I basically didn’t sleep that whole time. In the end, she somehow managed to persuade the doctor, and they stopped giving me the injections. After that, I didn't complain about the conditions."

Police and passers-by detain Shmonov in the Red square after Shmonov made two shots from a sawn-off sporting gun during the festive demonstration. Source: Sergey Subbotin/RIA Novosti

Police and passers-by detain Shmonov in the Red square after Shmonov made two shots from a sawn-off sporting gun during the festive demonstration. Source: Sergey Subbotin/RIA Novosti

Living in a fog

Shmonov says it took him five years to recover from this "treatment." He still needed to get out of the clinic though. "I don't know what saved me," he says. "My father was chief at a police station, a colonel. He ran around pestering everyone with letters, trying to go through different channels. When Yeltsin became president, I wrote him, ‘Dear Boris Nikolaevich, in 1990 I collected 200 signatures in your support, please help improve my situation.’ Then, during a psychiatric exam (these took place every six months, and I was always diagnosed with ‘delirium,’ that is, ‘incorrect judgment, unwilling to change his mind’) I decided to pretend that I had realized my mistake, that it had been wrong to shoot at Gorbachev, and I repented. In the end the committee determined that I was in a state of remission, and I was set free."

When I asked Shmonov if he thinks his actions were a mistake, he simply replied: "No. My relation to Gorbachev has not changed."

That said, Mikhail Gorbachev, who will turn 86 years old this year, does not need to worry. The person who once tried to kill him is now completely consumed by different schemes and inventions.

Source: RBTHvideo/YouTube

Read more: Why did Soviet Union's most notorious would-be-assassin shoot at Brezhnev?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox