A common practice among fraudsters was to add road dust to instant coffee, or to add salicylic and boric acids into beer.

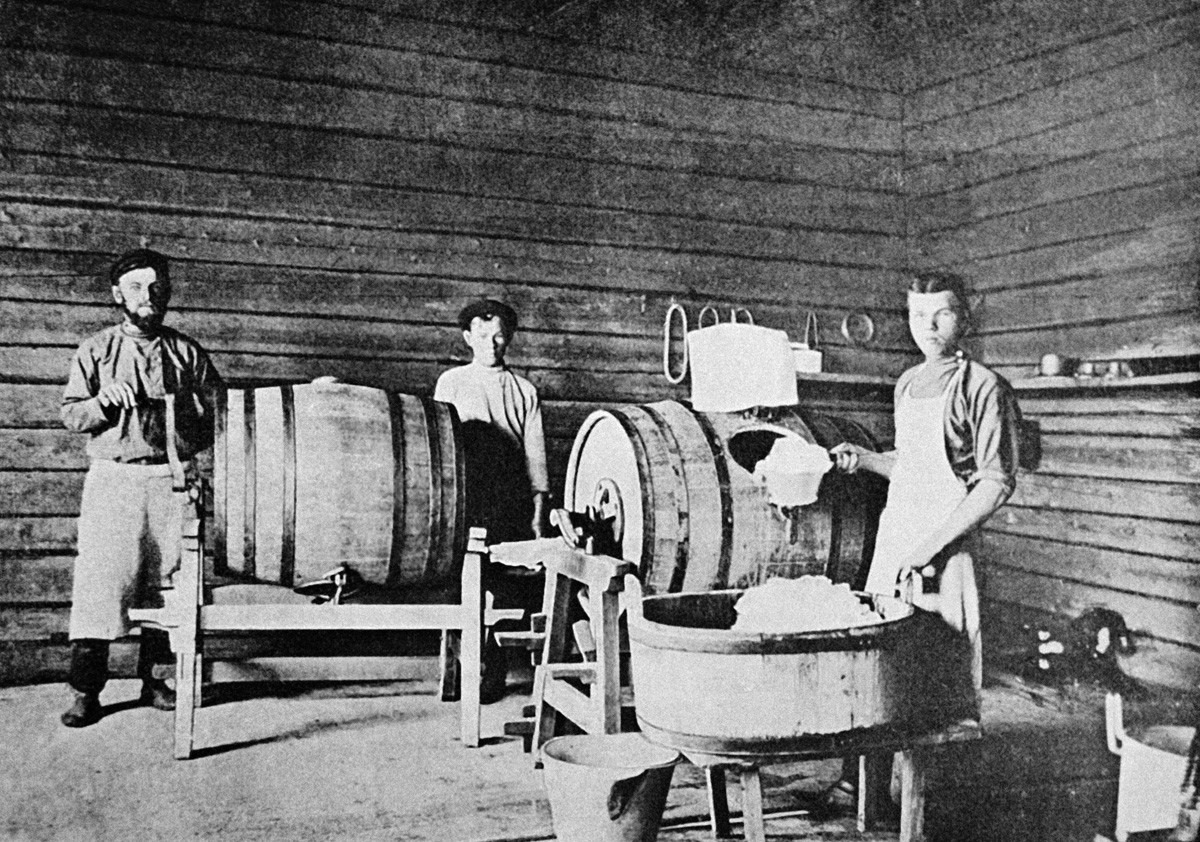

MAMM/MDF/Russia in photo, FreepikImperial decrees regulating market vendors, trying to stop them from selling rotten meat, first appeared in Russia in the 18th century during the time of Peter the Great. However, even police supervision couldn’t solve the problem, and so more punitive decrees were adopted in the mid-19th century. In 1855, a 100-ruble fine, or a month-long jail sentence, was imposed for "preparing to sell or selling food or drinks that are harmful to health or have gone bad.”

The decrees were usually issued after cases of mass poisoning or complaints from members of the privileged classes. They were meant to prevent food fraud, which at the time affected bread and meat, honey, sugar, and even breast milk surrogates. A common practice among fraudsters was to add lime to milk, or to add blue dye to sugar to improve its color. Olive oil was made by adding sesame and linseed oil, vinegar had hydrochloric or sulfuric acid added in order to give it extra strength; caviar was soaked in water or beer to increase its size. What other instances of food fraud were there at that time?

Tea came to Russia from China, spreading across the country from Siberian towns on the Chinese border. In 1821, Emperor Alexander I issued a decree allowing tea to be sold in taverns and restaurants, which triggered a boom in the tea trade in Moscow and other big cities. Merchants made vast fortunes from tea, but some resorted to trickery to boost profits: they added stalks, branches and waste tea leaves to their tea; or they sold fireweed or leaves of other plants (birch, mountain ash) as authentic Chinese tea.

According to records by the researcher, A.P. Subbotin, some merchants went as far as to recycle used tea leaves, which were collected from taverns and sent to factories, where they were dried again, tainted with copperas, graphite or soot, and then mixed with fresh tea leaves and sold again. To make tea heavier, it would be soaked or have lead shavings added.

The brothers Konstantin and Semyon Popov earned a reputation as responsible sellers of a tea drink. In 1898 their company received the title of supplier of the Court of His Imperial Majesty. However, they had to struggle with unscrupulous competitors.

Archive PhotoIn the late 19th century, there was the high-profile trial of two merchant brothers Alexander and Ivan Popov, who sold fake tea in packets with labels that looked very similar to those of a reputable tea trading house with a similar name, Brothers K. and S. Popov. At their trial, Alexander took all the blame and was exiled to Siberia for the rest of his life, but his brother was acquitted.

Read more: Why do Russians always drink tea (often with lemon)?

Coffee beans were as expensive as tea, and were in great demand by gourmets and fraudsters alike.

In the 1880s, St. Petersburg was the scene of several high-profile trials of criminals who made coffee beans out of clay, gypsum and mastic. To give their product the color and smell of coffee, the coffee sacks were rinsed in a solution made of coffee grounds. In addition, the police detected whole gangs of vagrants who, in unsanitary conditions, made coffee beans from wheat, barley, bean and corn dough, and roasted them in molasses.

In Moscow living room, in the 1840s. Boris Kustodiev.

“Pictures on Russian history”, edition by I. N. Knebel.Another "standard procedure" in the production of instant coffee was the addition of sieved road dust, that could comprise up to 30 -70 percent of the product. Other manufacturers added chicory, barley, or acorns to their coffee.

Read more: The parable of the Soviet coffee tree

Green peas became popular in Russia in the early 18th century thanks to foreigners, who brought them into the country. The product was popular but expensive.

In the late 1880s, several incidences of mass poisoning in St. Petersburg ended in a number of fatalities. The cause was canned peas tainted with a poisonous copper sulphate. The substance had been added to the product to cover up violations of the production process, and to give the peas their trademark green color.

Policemen at Sukharevsky market.

Collection of A.Melitonyan/ Russia in photo.The poisoning affected up to 1,000 people, so the fraudsters were quickly identified and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Butter was an expensive product, so unscrupulous traders adulterated it with pork or beef fat, or even with starch, soapy water or fish glue. In 1902, as a replacement for butter, a cheaper product – margarine - was created from a mixture of animal and vegetable fats, but even it fell victim to fraud. To cover the trick, adulterated margarine was tainted with carrot juice. The Finance Ministry started receiving complaints about "rancid fat," which triggered large-scale inspections across Moscow. It turned out that only half of the tested margarine samples had not been adulterated.

Read more: Vologodskoe: The legendary butter with aristocratic roots

“If beer turns sour, they put lime into it. Which, as you can see, sir, makes its look and smell quite pleasant for customers," says a waiter in a 1903 book, Moscow Bon Mot, by the chronicler of everyday life, Yevgeny Ivanov.

When samples were taken from bottled beer in Moscow and St. Petersburg, they were found to contain poisonous additives: salicylic and boric acids, calcium sulphate, etc. Sulfuric acid was used to make beer lighter in color, while glycerol was used to mask a strange taste and produce a thick beer head. Inexpensive beers also had bleach, wormwood and aloe added to them. After drinking a beer like that, many a customer tragically died.

Read more: How to make Ossetian beer

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox