At a kids' cafe, 1988.

Vladimir Semenov/TASSFor many, the final years of the USSR are associated with endless lines for some random goods that suddenly came on sale in a nearby store, and store shelves being empty, apart from never-ending canned fish. While others have fond memories of warm bread, milk that had a shelf life of just a couple of days, pastries with cream made from real butter, which even schoolkids could afford, and generous family feasts. We asked Russians who had first-hand experience of life back then what the food situation in their cities was really like.

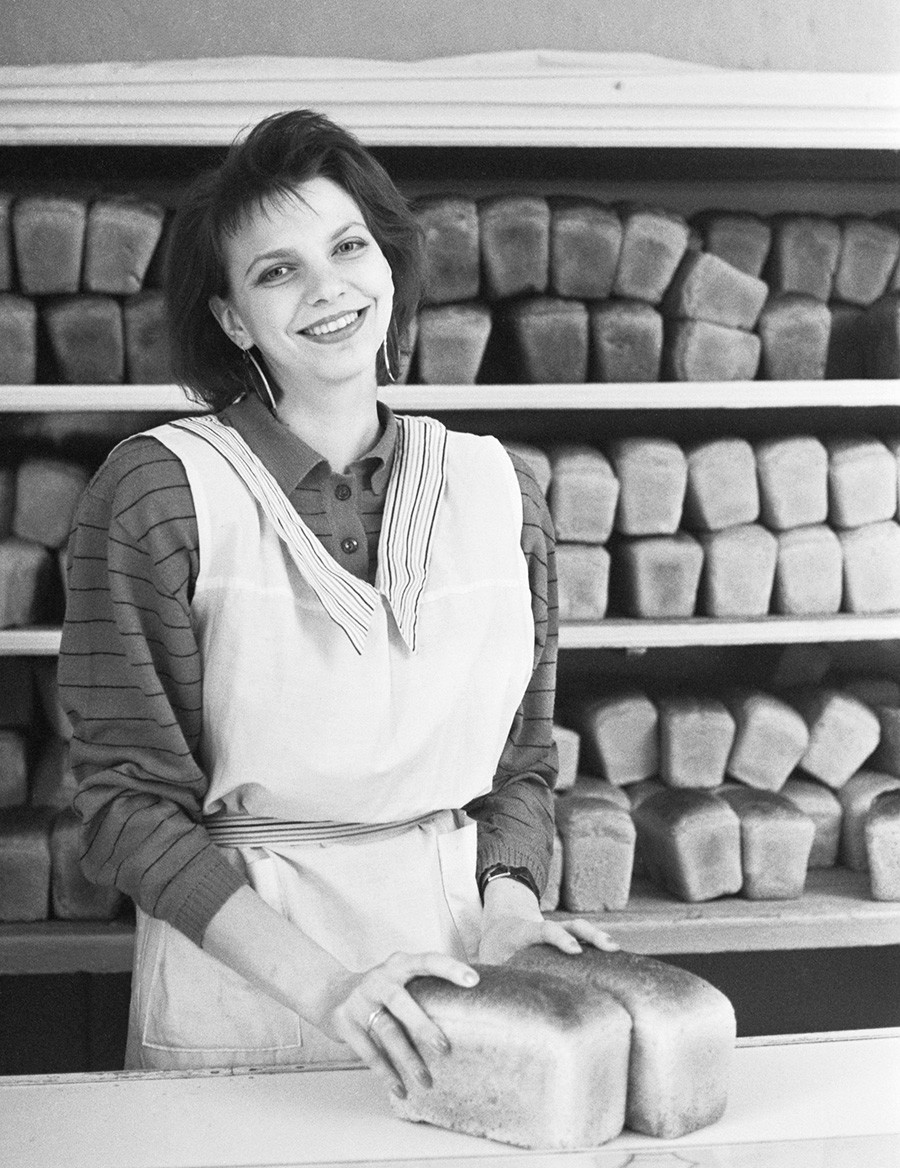

At the central corporate farm shop in Perm, 1989.

Yevgeny Zagulyaev/TASS“Breakfast usually consisted of semolina porridge; lunch was at home, consisting of an instant soup, and dinner, too. Sausages and cheese were a rarity. We had meat once or twice a week. But there was a great variety of pasta and vermicelli, although of rather poor quality,” says Alexey Karamazov from Yakutsk (Siberia).

Most foodstuffs were brought to Yakutsk from other parts of the country, with the exception of bread and milk. “The milk was fresh, it was sold from large yellow barrels. Bread was also local: there was a large bread factory in our city.” As for fruits and vegetables, they could be bought only in season. That said, he continues, in addition to ordinary stores, Yakutsk also had a market where one could buy practically everything, except that the prices there were not those that an ordinary person could afford.

The Okolitsa store, Perm.

Anatoly Sedelnikov/TASS“We were not starving,” says Olga Bozhedomova from Khabarovsk (in the Far East). “Dad went hunting and fishing, so we always had meat and fish. Which could not be said of the stores, maybe just with the exception of the central ones.”

As for fruit and vegetables, Olga’s family got those from their dacha, where they grew stuff and then made preserves for the winter. “Stores sold potatoes, carrots, beets, and cabbage, which would go a bit off by the end of winter,” she says.

“Dad used to say: our food is shchi (cabbage soup) and porridge [this Russian proverb means simplicity in food],” recalls Natalya Nechaeva from Perm (in the Urals). “On an ordinary day, we would have sauerkraut (we made buckets of it at home) and potatoes, then mother would bring cutlets from her factory canteen; meat was hard to get, same as sausages.”

Preparing for the New Year family celebration, Moscow, 1971.

Boris Kavashkin/SputnikPerm, too, had a market where everything was sold at exorbitant prices, Natalya recalls. But what you could always buy in a store was bread and milk. “It was a real joy when they distributed food parcels at the factory. In addition to chicken, which was always in demand, and a can of condensed milk, you also got two kilograms of sugar,” she says. Meat and fish were made to last longer by preparing dumplings, meatballs or fish cakes from them. “If you managed to get hold of mayonnaise and sprats, you saved them for the holidays.” As for cakes, people usually made them themselves or went to get them in Moscow, where you could buy everything, and at cheaper prices, too.

During the period known as “stagnation”, many Soviet cities experienced a shortage of essential goods, from meat to vehicles, which was caused, for the most part, by the shortcomings of the planned economy. However, this was not the case everywhere.

“In 1986-1987, I lived in Moscow and when I went back home to see my parents, I brought them coffee, sausage, cheese, Pepsi and Fanta. Moscow had it all,” says Natalya.

The confectionery department at Moscow's Yeliseevsky store. 1987.

Vyacheslv Bobkov/SputnikThe USSR had a system of so-called “supply categories”: special, first, second and third. The special and first categories included Moscow and Leningrad (St. Petersburg now), the capitals of the Soviet republics and “closed” cities; the second category covered most of the territory of the USSR, while the third consisted of the Far North (Yakutia, Chukotka, Murmansk Region and others). In addition, foodstuffs were given “zone prices”, which – among other things – depended on transportation costs. For example, in the first zone, a pack of sugar cubes cost 94 kopecks ($1.3 that time); in the second, 1 ruble and 4 kopecks ($1.4); and in the third, 1 ruble and 14 kopecks ($1.6).

This is how the "price belts" looked like.

Pikabu.ruIt is not surprising that residents of other cities often traveled to Moscow and Leningrad in search of sausage, meat, and cheese... People would buy sacks and suitcases full of food that was in short supply. There were many jokes about so-called “sausage trains”. Like this one, for example: The American president asks Brezhnev: “How do you manage to deliver food to such a large country?” - “It’s very simple: we bring everything to Moscow, and from there people transport everything themselves.”

Natalia says that they had relatives living in a military compound near Vladivostok (in the Far East), who every year sent them red caviar and fish to Perm. Whereas, Olga recalls that in Khabarovsk people had to line up to get dairy products. “In 1984, when I went on holiday to the Baltics with my parents, I ate syrniki (cottage cheese pancakes) with sour cream at the canteen for the whole month we were there, they were in ample supply there,” she says.

Novokuznetsk (Siberia), 1987.

Alexander Bobkin/russiainphoto.ruAt the same time, everyone remembers that although chocolate was in short supply, getting something sweet was not much of a problem. “Candies and cakes were brought from business trips to Moscow and Leningrad,” recalls Olga. “As for ice-cream, there was always a great variety of it, all very tasty. I remember vending machines in the streets selling soda, with and without syrup.”

“Shops in Perm sold candies made in Moscow and at a local chocolate factory,” says Natalya. “What you usually saw in the store windows were hard candies and toffees, so when chocolate candies appeared, we were over the moon. The Prague cake was usually brought from Moscow.”

Sweets produced at the Moldavian SSR's factory.

N. Matorin/Sputnik“With the start of the anti-alcohol campaign [1985-1987], sugar shortages began, then hard candies started to disappear too, as people would use them to make home brew,” Alexey recalls. “But you could buy jelly at 3 kopecks ($0.04) and ice-cream at 20 kopecks ($0.3) per 100 grams. These days, you can get everything you want in Yakutsk, all year round, to suit any taste and budget. But, in my subjective opinion, Soviet ice-cream still tasted better.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox