The first mention of coffee is found in Russian documents dating from 1665, when it was prescribed to tsar Alexei Mikhailovich as medicine for bloating, headache and runny nose. It is not known whether it helped the tsar at the time, but Peter the Great (who ruled the country from 1682 to 1725) was the one who really got a taste for coffee during his trip to the Netherlands in 1697.

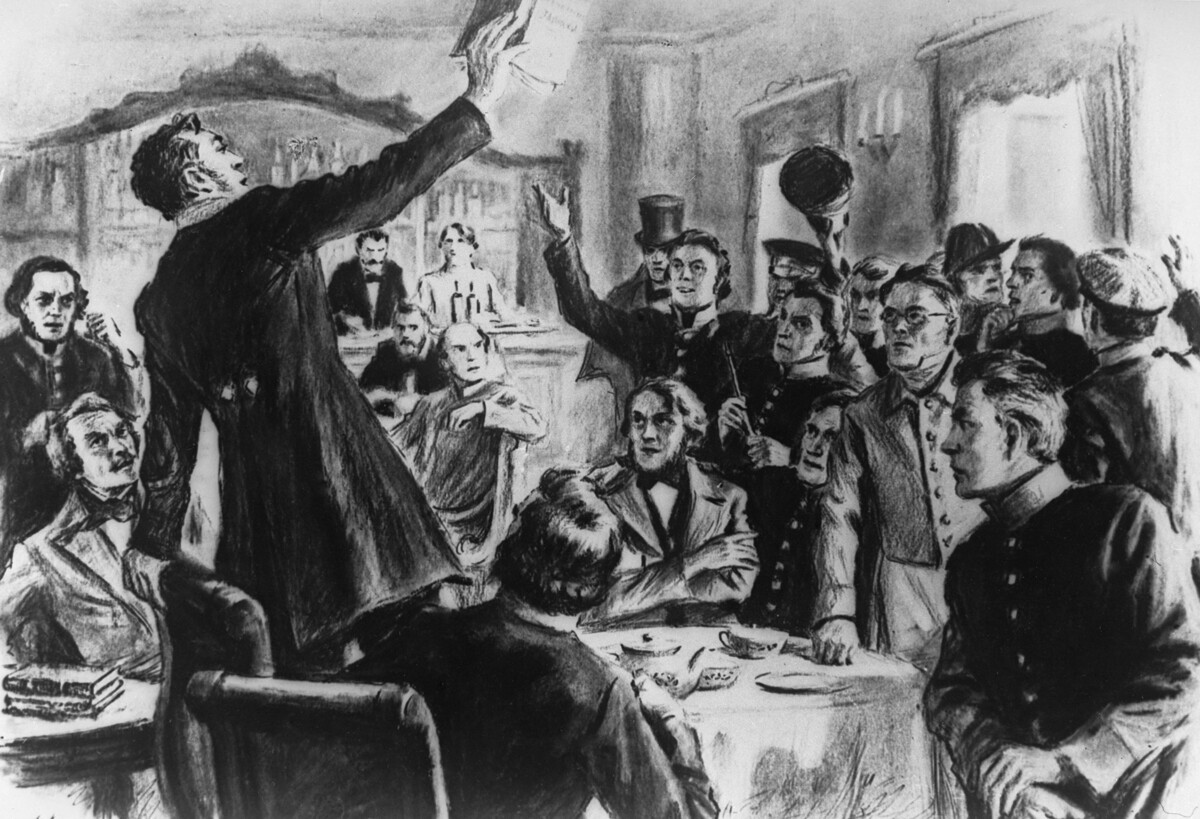

Assembly under Peter I. Stanislav Chlebovsky (1858).

Russian Museum/ Public DomainPeter tried coffee for the first time with the burgomaster of Amsterdam and the manager of the East India Company, Nicolaas Witsen. After Peter praised the drink, Holland began to export coffee beans from its plantations on the islands of Java, Sumatra and Ceylon to Russia.

Peter liked coffee so much that, at the opening of the Kunstkammer in 1714, the first museum in the country, he ordered: “Not only to let anyone come here for free, but if anyone comes with a company to look at the rarities, then treat them with a cup of coffee or a shot of vodka on my account.”

The tsar ordered coffee to be drunk at assemblies and the upper classes were forced to follow his orders, even though they found the drink to be intolerably bitter. By the end of his reign in 1724, there were fifteen taverns in St. Petersburg where you could drink coffee. However, they were mostly frequented by foreigners.

Many of Peter’s innovations were not liked by the Russian clergy and coffee was no exception. The following proverbs appeared: “Tea is cursed at three councils, but coffee at seven” (a council is a meeting of church representatives), “Potatoes are cursed, tea is cursed at two, tobacco and coffee at three”, “God will kill anyone who drinks coffee.”

Portrait of Catherine the Great, 1770. Fyodor Rokotov.

Hermitage/ Public DomainThe first coffee house where you could buy coffee beans appeared in St. Petersburg in 1740, thanks to Anna Ioannovna, Peter the Great’s niece. She was a passionate fan of coffee and drank it every morning.

Coffee houses were owned by natives from the Netherlands, Germany and England. They brewed coffee in copper or tin pots, filtered it and then drank it the way they used to back in their homeland. For example, the German way was to drink coffee without any additives. The Viennese way was to drink coffee with whipped cream.

It had been rumored that another Russian empress with German roots, Catherine II, drank up to five cups of strong coffee per day. It took 400 grams of ground coffee beans to make one cup. Allegedly, when one of her servants drank a cup of coffee offered by the Empress, he almost died from cardiac arrest.

Students in coffee houses. Reproduction of the drawing by B. Lebedev.

TASSWith the spread of coffee, coffee grounds fortune-telling became popular. It was first mentioned in mid-18th century documents. By the end of the century, printed books with instructions on how to interpret coffee “symbols” appeared. At high class balls and receptions, there were even so-called “coffee women”, who claimed to be able to determine the future by looking at what was left at the bottom of a cup of coffee.

There is a legend that, in 1799, a gypsy woman foretold Russian Emperor Paul I’s forthcoming demise, for which she almost paid with her life. The emperor, as we know, was murdered in 1801.

However, such entertainment, just like coffee itself, remained a privilege of the nobles. Common folk had no access to coffee until the beginning of the 19th century.

Coffee pot.

Legion MediaIn 1805, during the War of the Third Coalition (also called the Russo-Austro-French War), while in Austria, Russian troops saw the local population drinking coffee with pleasure. The soldiers nicknamed it ‘kava’ and became addicted to it. It is believed that at first, they were slurping it with spoons from large plates like soup.

Along with the military, coffee came to Russia not only from Western Europe. Cossacks who served on the border and fought in the war with the Ottoman Empire (1806-1812) captured sacks with coffee beans and kettles for brewing them. Thus, coffee became popular in the Azov Sea region and the Caucasus. A tradition was formed among Cossack women, where they would invite their female friends and relatives for coffee at noon. Coffee was usually served with heavy cream or spices.

A samovar with two taps for tea and coffee made in the early 19th century.

Nikolay Pashin./SputnikThe appearance of samovars-coffee pots in 1820 further evidenced the fact that coffee gradually entered the homes of all population segments in the 19th century. Externally, they looked like flattened cylinders with flat handles parallel to the body. Such a samovar had a frame with a hinge, to which a bag with ground coffee beans was attached. Samovars for coffee were made in two sections. One section was for tea, and the other one was for coffee.

Coffee and vodka, 1913.

Frédéric de Haenen / Public DomainAt the same time, there were ways to save money on coffee: chicory was added to it or it was brewed from foreign products (roasted barley flour, chopped acorns, beets, pear seeds, watermelon peels and dandelion roots). (Check out how food vendors in Imperial Russia committed fraud).

Coffee advertising, late 19th - early 20th century.

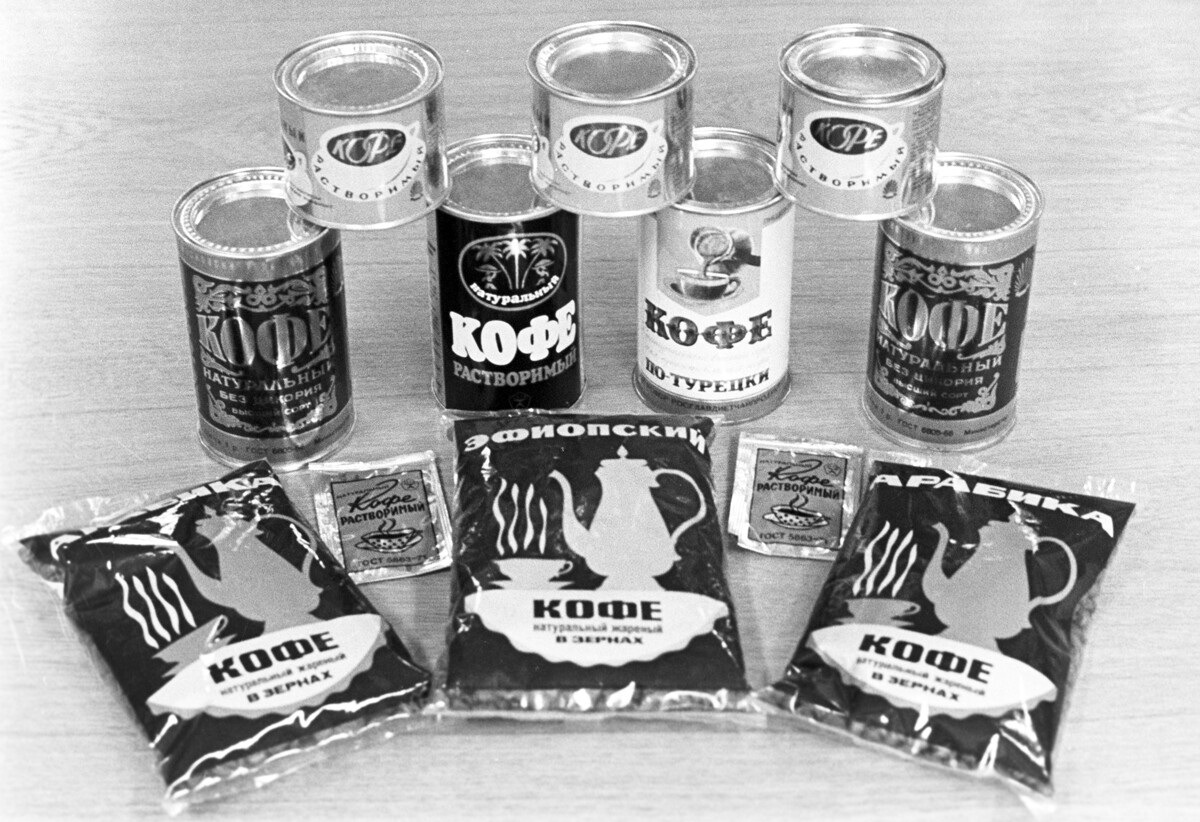

Public DomainBefore the outbreak of World War I, coffee imports to Russia were constant, but, during wartime, it became a luxury item. By 1930, coffee started to become imported once again, but remained an expensive and scarce beverage. Coffee became more affordable only during Leonid Brezhnev’s rule (1964-1982). The Secretary-General himself liked to start his morning with a cup of coffee with milk. At that time, most of the supplies came from Brazil and India. In 1972, the USSR started its own production of instant coffee.

Coffee is a product of the Moscow Food Mill.

Boris Babanov/SputnikDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox