The ryumochnaya is a purely Soviet phenomenon. It is a special snack bar in a Spartan format. It specialized in strong alcoholic drinks, with sandwiches served as appetizers or snacks. At some point, these “snack bars” turned out to be a form of “cultural recreation” available to most Soviet people.

“Men who usually drank port by their building entrances, like revolutionaries who gathered for a meeting in the basement or under a painted wooden mushroom figure on a children’s playground, could now go to a proper establishment, knock back a shot and intelligently have a bite of sandwich as a snack. Such a thing was not even dreamt of at that time,” journalist Leonid Repin wrote in ‘Stories about Moscow & Muscovites throughout time’.

The first USSR shot bars opened in Moscow in 1954. According to Moscow historian Alexander Vaskin, this was a political move by the new head of state, first secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Nikita Khrushchev. He had to quickly win the people’s love and authority.

“The idea to open shot bars in Moscow was not just good - it was fantastic! By creating a network of shot stores, the Party and the government showed great care for the health of the people and their cultural leisure,” Leonid Repin wrote.

They were designed to make lovers of liquor and vodka products more “cultured”, so that they did not drink in public places. But, some places became a refuge for citizens who could not find a place for themselves in the post-war USSR.

“At the corner of Mayakovskaya and Nekrasova streets [in Leningrad - ed.], there was a terrible drinking parlor full of legless invalids. It smelled of damp sheepskin, misery, shouting, fighting… it was a terrible post-war shot bar. There was a feeling that the people were deliberately made drunk there - all those ‘stumps’, ‘crutches’, former officers, soldiers, sergeants. They couldn’t find a way to keep these people warm and busy and this was one of the ways out,” writer Valery Popov speculated.

They poured vodka, port wine, liqueurs, wine and cognac in shot bars. Each shot was served with a modest snack - a sandwich with sausage, cheese, eggs, herring or sprat. There were four sprats on a sandwich, which was supposed to go with a 100 ml shot.

“There was only one inconvenience: after one drink, I wanted to drink some more and I had already had more than enough sandwiches. In general, it all happened like this: men stood there, knocking over shot after shot while making the ‘Leaning Tower of Pisa’ out of piles of sandwiches,” recalled Repin.

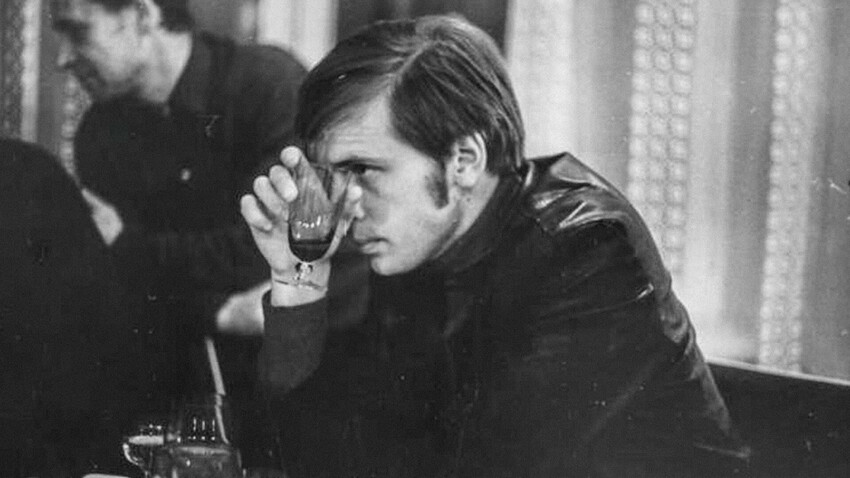

There were no tables or waiters in shot bars. Visitors lined up, received simple orders from the barmaid and then went to the bar tables.

Soviet writer and publicist Daniil Granin described a shot bar: “This is a glorious place - the smell of vodka, cigarettes, only men and without the forced drunkenness of bars, without molestation, sticky lingering conversations. Drank a shot, ate a sandwich, quickly and delicately.”

Simplicity implied low prices, so almost any citizen could afford to go to a shot bar. Prices and sandwich varieties were the same throughout the Soviet Union, recalls Alexander Vaskin.

“Prices were just kopecks. Everything happened in silence, with a sense of dignity. You drink up and then move on home or to see somebody or to the Philharmonic,” St. Petersburg historian Lev Lurie describes the advantages of a shot bar.

In general, the visitors of such places were mostly decent.

“A factory worker and a journalist, an engineer and a plumber could all get together in a shot bar. It was not only a men’s club of interest, but also a place that attracted different people. It was possible to conduct sociological surveys and study the structure of society in them,” says Alexander Vaskin.

And the state did study it. As Lev Lurie notes, in the 1950s, almost half of political cases were initiated because of freethinking at shot bars.

“The ryumochnaya remained a haven for skilled, intelligent workers, who determined the social appearance of the city: serious, hardworking men who go fishing, watch soccer, take vacations in their factory’s preventorium or at the dacha. These establishments for visitors who had finished their work shift played the same role as pubs did in England,” he writes.

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev, general secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, initiated an anti-alcohol campaign. Its active phase lasted for two years, with the country reducing the production and sale of strong alcohol.

The measures also affected the shot bars.

The next blow to them was the collapse of the Soviet Union. The formation of the restaurant market in the country and the emergence of new formats of catering reduced the shot bars to the role of “nostalgic” establishments, frequented by an aging, but loyal audience.

“Rumochnayas were never rebuilt nor did they disappear anywhere. They remained, like the Rostral Columns, Zenith and ‘White Nights’, without changing their function. <…> The average age of visitors now is close to the retirement age: almost all of these people were brought up, knowing the simple and raw nature of a shot shop from childhood. All those who drank a lot, died, having failed to survive the 1990s. Only tough veterans now remain, who know their limit and are used to ‘cultured’ drinking,” Lev Lurie characterizes the situation in St. Petersburg.

He emphasizes that it is in the Northern Capital that the shot bars have retained their popularity: according to Lurie, there are more of them than in Moscow, yet it is difficult for old places to attract a new audience.

“Shot shops don’t lend themselves to stylization. There have been several attempts to create something in this genre for a younger and better-off audience. They’ve all failed. Young people drink much less than their fathers and grandfathers and they are not hooked on vodka. Local hipsters prefer to have a ‘shot’ in a trendy bar somewhere on Dumskaya or Fontanka. But, real connoisseurs of the genre have not rushed to the new establishments - it is expensive. The shot bars are still alive, but they are slowly dying out along with their customers, like thick table magazines or a game of dominoes in the yard,” concludes Lurie, a St. Petersburg resident.

In Moscow, St. Petersburg or any other city in Russia, it is not a problem to find a shot bar: establishments in this format continue to open. Nevertheless, not all owners adhere to the principles of “old-school” shot bars; namely, simple, cheap and democratic. And any Soviet-styled “neryumochnaya” (non-shot bars) will still correspond to modern restaurant realities in terms of its interior and menu.

In the meantime, the genuine Soviet “ryumochnaya heritage” is hidden under inconspicuous signboards, in basements, visited by “their own” kind. It is cheap and cheerful, not fashionable at all, but authentic. The only difference is they have normal tables and chairs now.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox