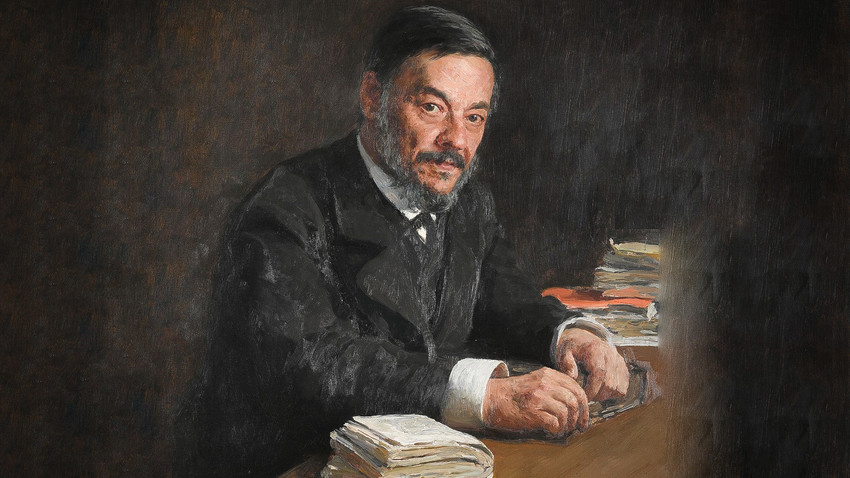

Portrait of doctor Ivan Sechenov by Ilya Repin.

Ilya Repin/Tretyakov Gallery

Specialization: surgery

Mid-19th-century medicine was a dirty and bloody business, especially during war. Surgeons were unfamiliar with antiseptics or general anesthesia. The most popular method of treating wounds was amputation – not only in Russia but elsewhere. Generally, soldiers were more likely to die of a disease than on the battlefield.

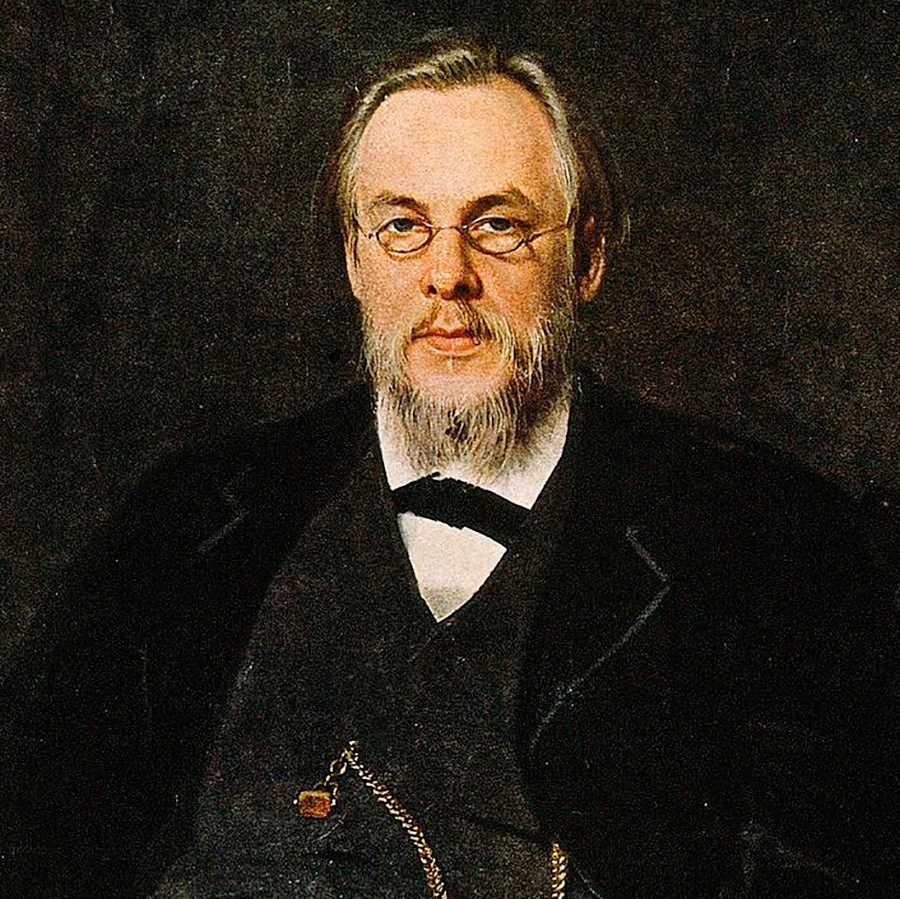

During the Crimean war of 1853–1856, Professor Nikolay Pirogov, who had been working on progressive surgery methods in St. Petersburg, changed the situation for better. He implemented ether-based anesthesia in combat conditions that reduced the suffering of wounded soldiers, organized a proper evacuation system, and effectively fought the spread of infection. Russia lost the war but medicine won big, thanks to Pirogov.

In civilian life, Pirogov was just as successful. He introduced the use of plaster casts for fixing broken bones, created one of the most detailed anatomical atlases of his time and even once treated Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi’s wound. Russia’s surgeon #1 had lots of students who went on to be great healers themselves, including ones from this very list.

Specialization: physiology

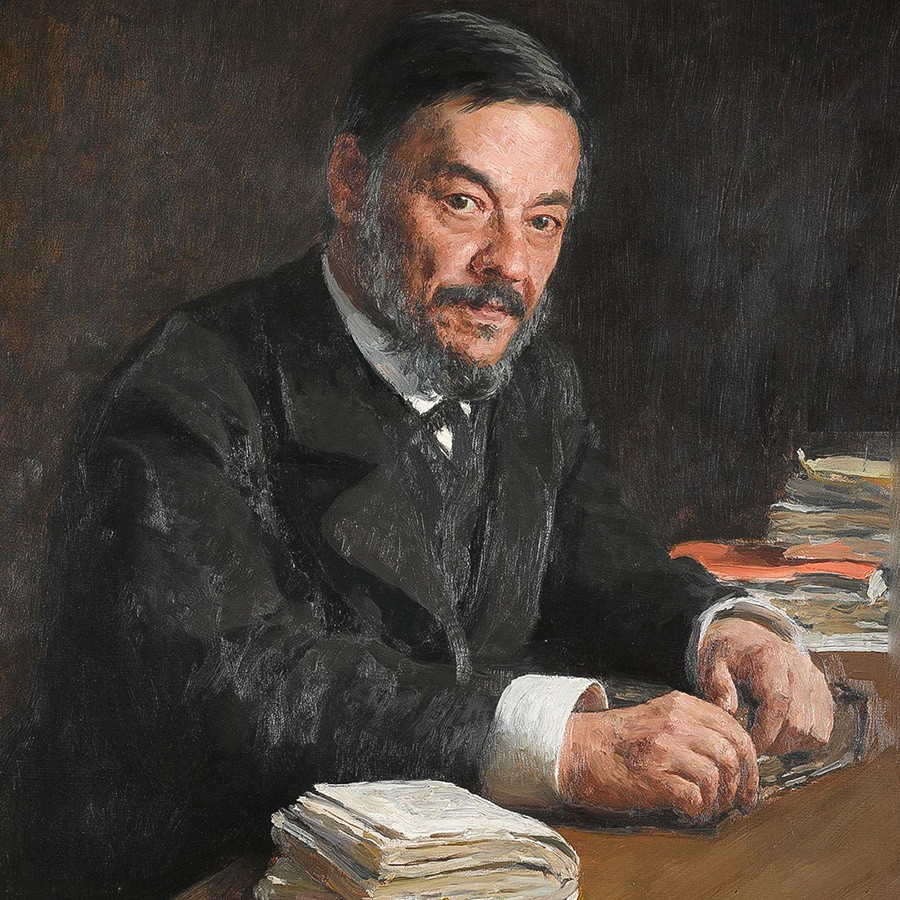

“Medicine hardly is a science… we know nothing of the genesis of diseases, we don’t know why exactly some treatment helps or not,” a young and perplexed medical student Ivan Sechenov wrote in his diary in 1850. He was right – in the 19th-century doctors knew how to treat diseases but not what caused them. After becoming a scholar, Sechenov became the one to change it.

He studied in Germany, conducted long-term experiments, and became the first Russian specialist in physiology, giving the discipline the serious scientific basis it lacked. His fundamental work Reflexes of the Brain remains a milestone in neuroscience and the study of reflexes. Back in his day, conservative officials attacked Sechenov for undermining the concept of a God-given human soul, but time proved him right; today his authority is unquestioned.

Specialization: surgery

Pirogov’s student Nikolay Sklifosovsky took part in four European wars from 1866 to 1878, always as a surgeon who saved lives. In Russia, he became the first surgeon to implement the methods of antisepsis and asepsis in operations.

At first, he was laughed at. One of his colleagues, skeptical of infection studies, joked: “Sklifosovsky is so big (he was tall) and fears tiny bacteria that can’t even be seen with the naked eye.” Predictably, this medic was wrong, and Sklifosovsky proved to be a star. Today, the biggest trauma and emergency hospital in Moscow is named after him.

Sklifosovsky also championed women in medicine. During the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1888, he headed Russia’s first female surgical team, though many of his colleagues were shocked. “We are so grateful that you let us practice,” a female doctor wrote to him later.

Specialization: clinical therapy

Sergey Botkin was a kind of Russian 19th-century Dr. House, a genius diagnostician digging deeper than anyone else in his search for the roots of disease. “There were no healthy people for Botkin and every person he saw interested him as a patient first and foremost… Diagnostics was his passion,” wrote Sechenov about his contemporary.

Botkin implemented a progressive method of collecting the medical history of patients: first, he scrupulously studied them physically, then quizzed them about their complaints. Botkin headed St. Petersburg Medico-Surgical Academy, treating both members of the royal family and ordinary citizens as well.

In terms of science, he created the theory of the organism working as a whole, independent system with different organs interacting within the body. Before that, medics treated different diseases separately, paying little attention to the work of the organism in general. Thus, Botkin came to establish the modern theory of clinical medicine.

Doctors around the world work without borders. To prove it, we have a story on how the American medics saved a Soviet girl in the most chilling moment of the Cold War.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox