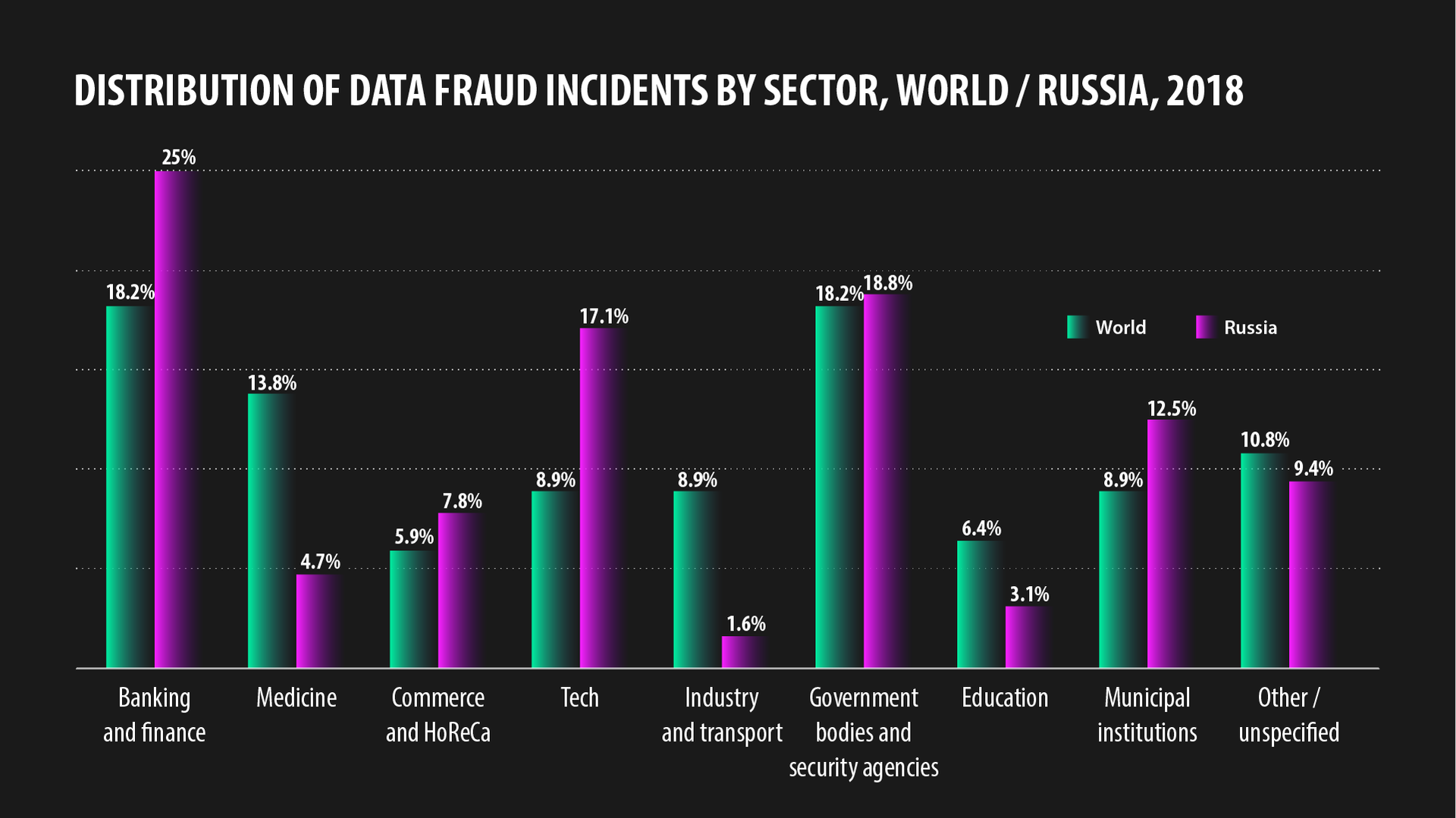

Above all, scammers are interested in money. Therefore, their main target is banks and financial institutions, which account for 25% of all leaks in Russia (according to a 2018 study by InfoWatch, a Russian company specializing in information security in the corporate sector). 18% of leaks (not that much, but still noticeable) happen at government bodies and law enforcement agencies. Hackers are also interested in tech companies (17.1%) and municipal institutions: city administrations, cultural centers, recreation camps, document-issuing authorities, etc. (12.5%).

Nor are shops and hostels immune to leaks (4.7%).

Leaks have also been reported at Russian medical (4.7%) and educational (3.1%) institutions. The least leaky sector is transport and industry (1.6%).

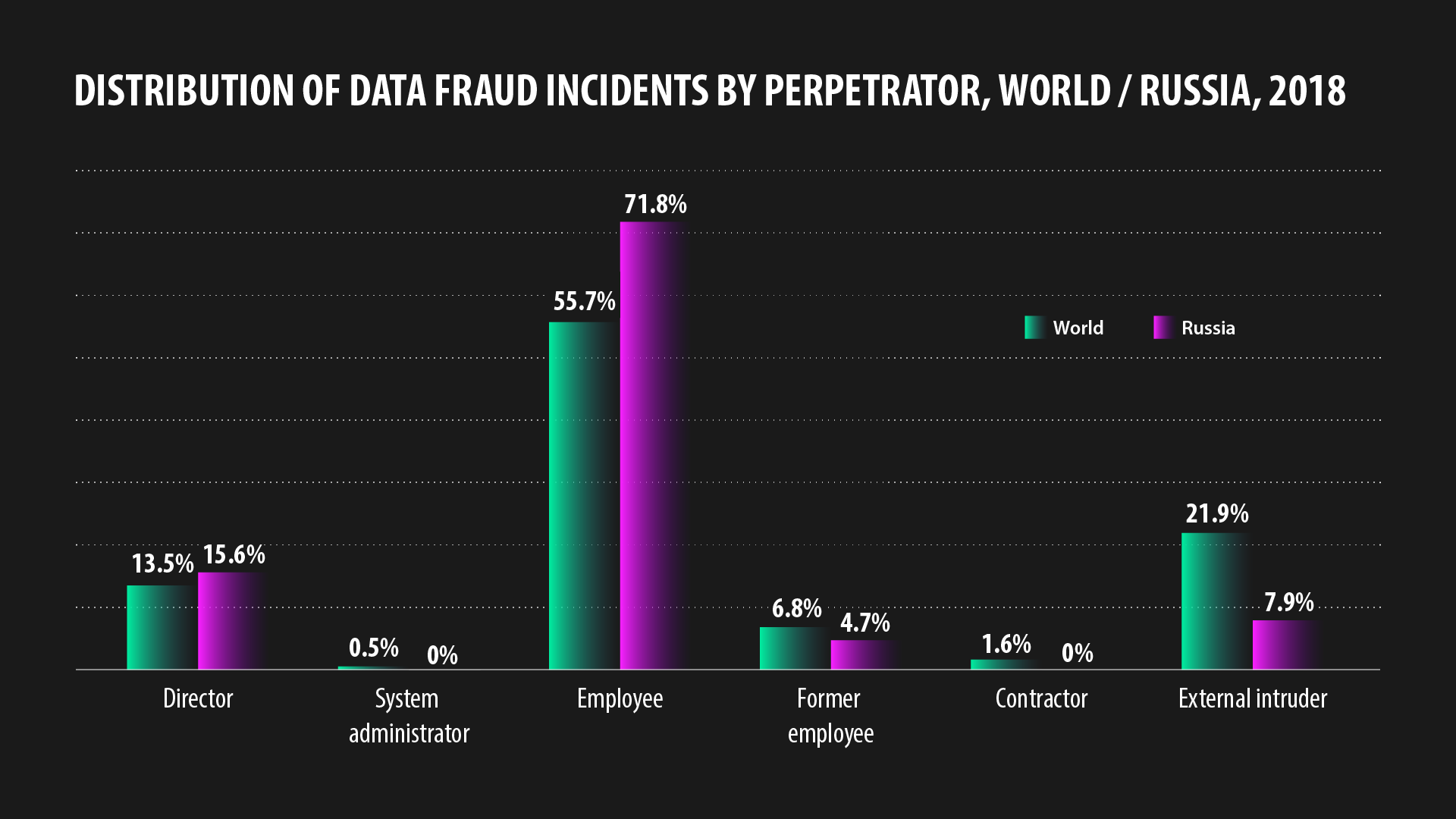

In the vast majority of cases (71.8%), the finger of blame points at ordinary company and government employees. Outside Russia, this figure is significantly lower (“only” 55.7%). Data breaches are committed by company directors too (15.6%). Slightly less danger is posed by external intruders (7.9%), even less by former employees (4.7%).

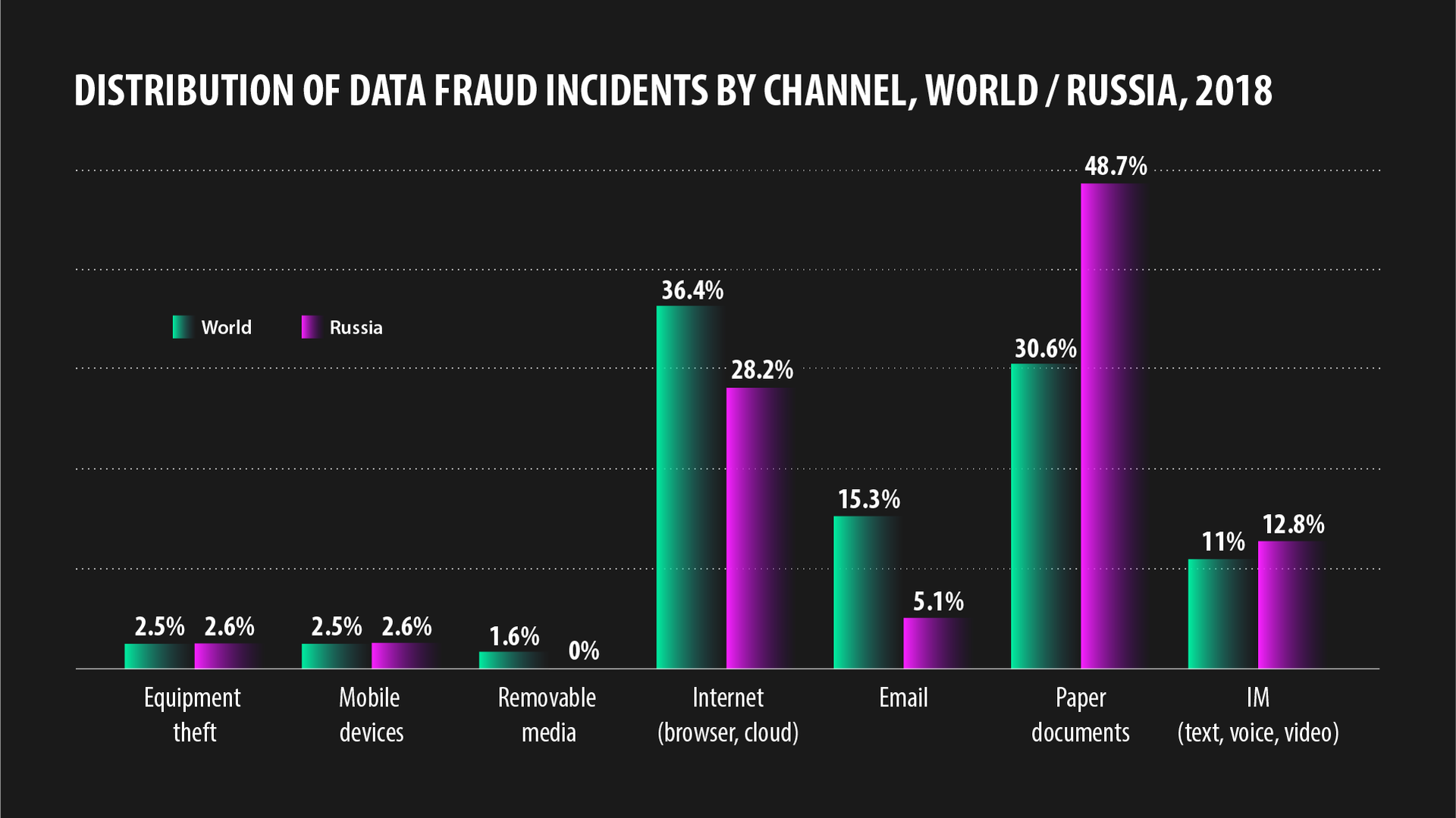

In Russia, despite the digital advance, the storage medium of choice for many remains good old-fashioned paper (what if the computer gives up the ghost?) Therefore, almost 50% of incidents are down to negligence with paper documents. The rest occur through browsers, email, cloud services, flash drives, smartphones, and instant messengers.

For example, in August 2018, a woman in Moscow discovered a huge “dump” of personal data overflowing with passports, police/migration documents, criminal case files, and a whole lot more.

The press service of the Moscow division of the Ministry of Internal Affairs later announced an investigation and promised that those responsible for the breach would be held accountable.

One of the largest leaks in 2018 involved Russian Internet company Yandex.

In the Yandex engine, it was briefly possible to search by Google Docs content, including internal bank and government documents. Yandex plugged the hole in less than 24 hours, and explained the blunder by saying that the search results displayed only files whose owners themselves had granted access to them via a hyperlink, without entering login credentials.

No, sometimes employees do it to earn a bit of extra cash.

Sergey Golubev, a manager at Russian mobile operator Vimpelcom, was well aware that Russian law prohibited the disclosure of telephone conversations. However, an unknown client suggested that he do a spot of spying on a certain subscriber. The task was to report all personal information revealed in the target’s calls and SMS for a cash reward. Golubev agreed, but the story ended badly for him when he was fired from his job and fined 100,000 rubles ($1,600), as reported by the joint press service of the courts of St Petersburg via Telegram.

How much Golubev was paid is unknown. Meanwhile, 31-year-old Lyubov Aganina from Volgograd, an employee at a local social welfare center, used other people’s data to steal 4.1 million rubles ($65,000) during the period from October 2016 to May 2017.

The scheme worked as follows: She issued social benefits to people whose data was provided by an acquaintance of hers and who were not entitled to benefits. The money was then sent to their bank accounts. The fraudsters then cashed and kept the money.

Her accomplice was sentenced to three-and-a-half years in jail. Aganina was handed down four years, but under Russian law, her punishment will take effect only when her son turns 14 (he is currently seven), giving her a near seven-year reprieve.

You bet. In the fall of 2018, cybercriminals uploaded a database of Sberbank employees to the dedicated forum phreaker.pro. It was a 47 MB text file containing more than 421,000 records with names, surnames, and login details.

In early June this year, client databases of three Russian banks (OTP, Alfa Bank, Home Credit Bank) were made public. Among the information were the names, phone numbers, passport numbers, and place of work of 900,000 individuals. The leaks were discovered by DeviceLock, a Russian anti-leak software developer.

InfoWatch points to several reasons. For one thing, the introduction of information security tools in Russia is generally slower than the pace of digitalization. Add to that the fact that Russian society on the whole has yet to develop a responsible attitude towards other people’s data, says the report.

Managers of mobile operators, bank clerks, police officers, and company employees view such data as their own, and believe they can do what they want with it. And even if they can’t, who cares.

The authors of the study believe that large companies and authorities are generally quite good at protecting their data against external attack. So the focus right now is on teaching employees how to handle their own data.

For example, the Russian banks UniCredit, VTB, and Otkritie have banned employees from photographing monitors on their smartphones. Otkritie has also forbidden taking shots of official documents, presentations, and client data, as well as recording official talks on a dictaphone.

Whether banks that have already suffered a leak have acted likewise is unknown.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox