Why is Siberia warming faster than anywhere else on the planet?

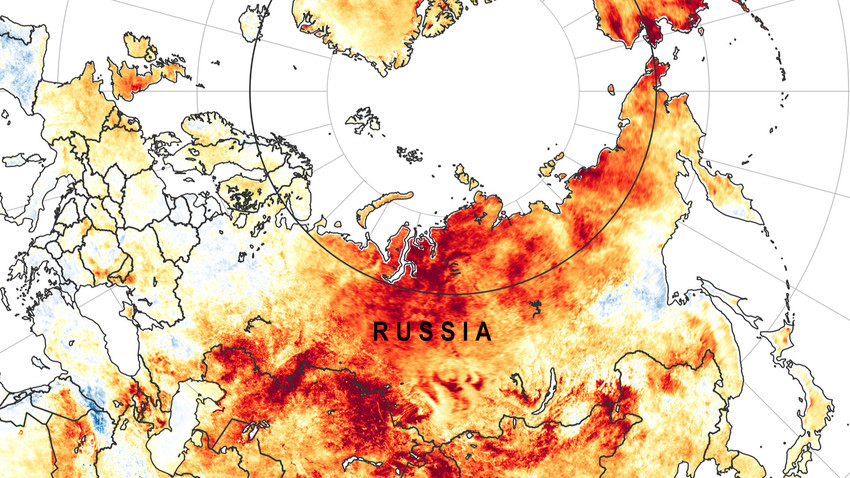

“Cherry winter” is what Russian meteorologists unofficially dubbed the last “cold” season. When the temperature in winter rises above the climatological norm, it is marked on the map in light red. The 2019 chart looked like someone had spilt wine over it.

Temperature records in Russia are now familiar news. The most recent came on June 20, when French meteorologist Etienne Kapikyan recorded a balmy +38ºС in Siberia’s Verkhoyansk, the coldest town on Earth. That happens to be the highest temperature ever recorded inside the Arctic Circle.

🌡️🔥 T°max de 38.0°C à #Verkhoyansk, #Sibérie orientale (67.55°N), ce 20 juin.

— Etienne Kapikian (@EKMeteo) June 20, 2020

Si cette valeur est correcte, ce serait non seulement un record absolu à la station (37.3°C, 25/07/1988) mais aussi la température la plus élevée jamais observée au nord du cercle polaire #arctique ! pic.twitter.com/EUE8JVdkGR

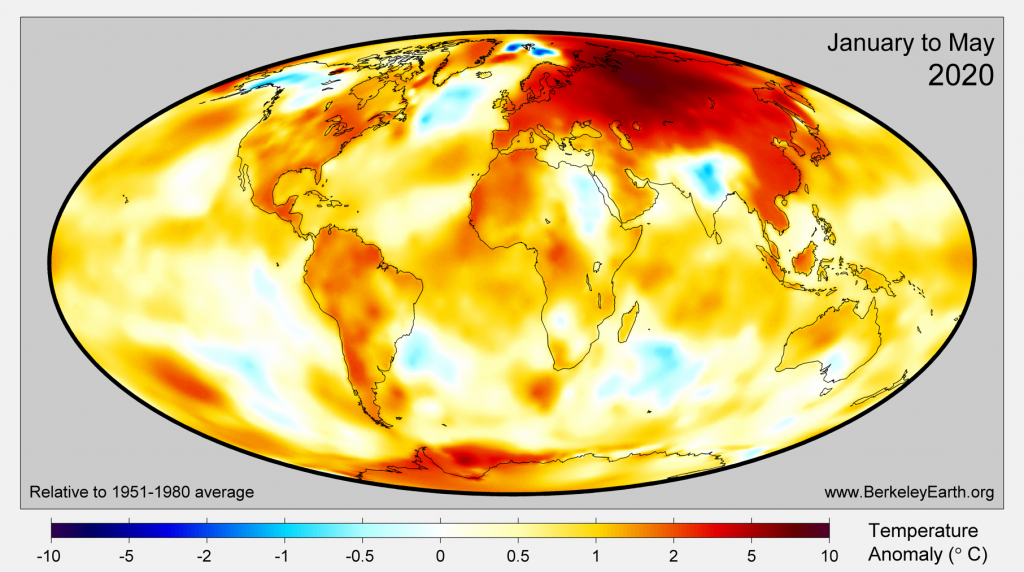

Abnormally high temperatures have swept Western Siberia since January 2020, with May being the hottest on record for the region. Elsewhere in Russia, fur coat sellers and ski resort owners have also been counting their losses.

Scientists report that Russia, two-thirds of which is covered by permafrost, is warming faster than anywhere else on the planet.

Why is Siberia so warm?

There are several reasons, and what we are observing now is their cumulative effect.

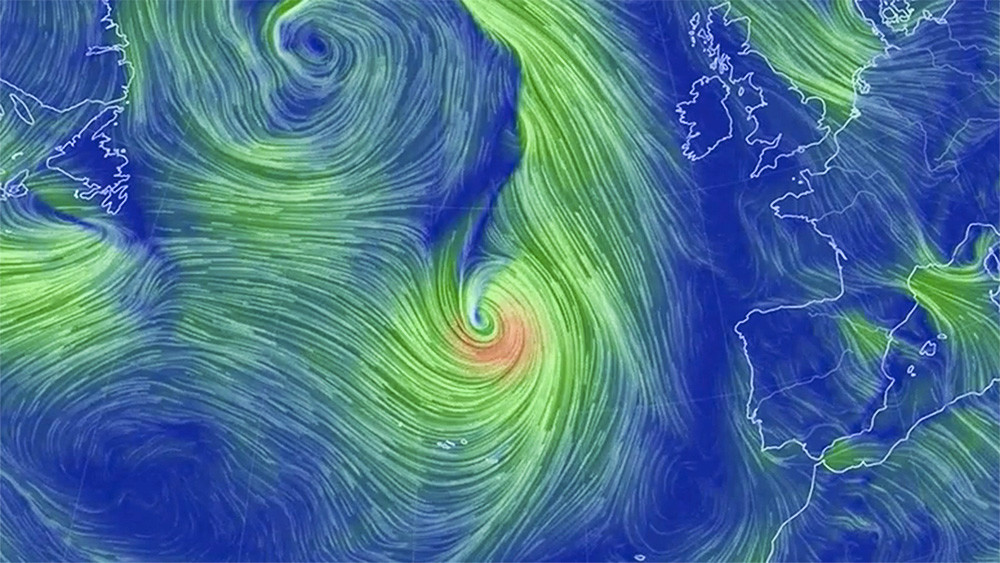

As noted by Alexander Kislov, doctor of geographical sciences, the weather in Russia (like in Europe) depends on the behavior of two giant vortices — one (anticyclone) is located in the Azores in the Atlantic, and the other (cyclone) in the region of Iceland. It turns out that the intensity of these vortices tends to vary synchronously. And when both are raging, “they cause a huge stream of warm moist air” to move over the continent. He says that last winter the vortices were especially strong.

Pavel Konstantinov, senior lecturer at the Department of Meteorology and Climatology of Moscow State University, told Russia Beyond that the warm winter in Russia is a consequence of the pressure distribution across the northern hemisphere this year. So in his view it is erroneous to consider the current anomaly to be a direct result of global warming. It’s not that simple. “It doesn’t mean all subsequent winters will be like this. It’s not the new norm,” Konstantinov believes.

What cannot be disputed is that the abnormally warm winter led to a dry spring and low moisture levels in the surface layers of the soil in many areas. This in turn could lead to more major forest fires in Siberia. In late summer last year, they covered about 2.5 million hectares, and this year, according to the Washington Post, more than 600,000 hectares of forest have already burned down.

The climate changes are particularly apparent in the Arctic region. “The Arctic is warming as a whole, while in Siberia the changes are not uniform,” adds Konstantinov. “But Arctic and Siberian warming are not directly related. It’s getting warmer in the Arctic because of the higher latitude.”

Novosibirsk, Russia on May 13.

Kirill Kukhmar/TASSOverall, Russia is warming about 2.5 times faster than the global average, Andrey Kiselev, lead researcher at the Voeikov Main Geophysical Observatory, is sure. “It’s due to geographical features: we live in a single belt where the land area significantly exceeds the water surface. The ocean, as a huge heat accumulator, can neutralize the impact of the changing conditions, but land has a completely different heat capacity.”

And this has consequences.

What next?

“Throughout my long career as a specialist, I’ve never seen such huge and fast-growing caterpillars,” says Vladimir Soldatov, director of the Forest Protection Center in Krasnoyarsk Territory. In particular, he is talking about the Siberian silkworm, which feeds on tree bark, buds and needles, and in warm conditions can grow to considerable dimensions.

Siberian silkmoth (Dendrolimus sibericus)

United States Department of AgricultureHuge moths may surprise and even delight entomologists, but that’s not the issue: caterpillars destroy forestland and make it more vulnerable to fire. This year, the silkworm was spotted 150 km north of its usual habitat zone, and is believed to have already caused the death of more than 120,000 trees.

Another significant problem is anthropogenic disasters, like the one that happened in Norilsk in June this year. According to one version of events, climatic changes caused the bottom of a storage tank to corrode, resulting in a spill of more than 20 tons of oil. In the words of Georgy Safonov, director of the Center for Environmental and Natural Resource Economics at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, over 5,000 oil spills occur every year in permafrost areas due to accidents involving oil pipelines. What’s more, absolutely all the infrastructure in Russia’s northern regions is decaying fast due to moisture and condensation in the walls; new buildings fall into disrepair after just 7-9 years.

Lastly, the so-called “zombie fires” in the Arctic are starting to increasingly worry scientists. These are fires that survive underground during winter, even under a layer of snow, and can reemerge the following spring. “This year saw an unusually large number of winter peat fires,” notes Grigory Kuksin, head of Greenpeace Russia’s firefighting team.

In actual fact, the phenomenon is far from new, and is observed every year in some region of Russia, says Konstantinov: “In the 1970s, the peatbogs around Moscow smoldered in secret, which made the winter snow black. We all saw it.” Or take, for example, 2010, when all of Moscow was shrouded in smog due to burning peat. But fires of this kind are creeping northwards, into regions where they are atypical. “Such fires are uncharacteristic for the Arctic, yet they are starting to appear there too,” the expert notes.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox