“Do you want Jurassic park? Because this is how you get Jurassic park.”

“Stop. Freeze that worm back up. This is 2020 we don’t need another catastrophe.”

“I have a bad feeling…”

The news that Russian scientists had “thawed” ancient nematodes (roundworms) from the Siberian permafrost first broke in 2018. Back then, articles describing the event appeared published in Russian and foreign scientific journals. Recently, however, someone remembered about the worms, the story went viral, and 2020 had another meme on its hands: “Hah, it’s just preparation for the sequel. 2021” — and the like.

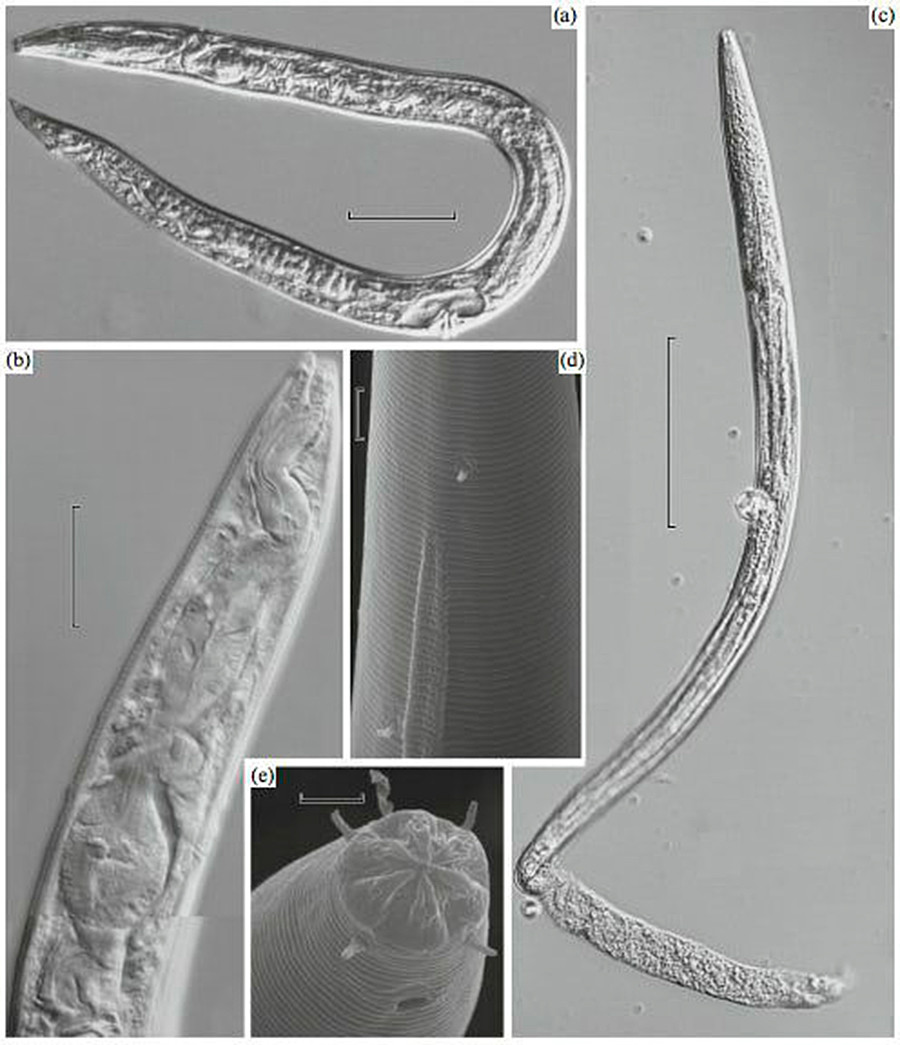

All the while, the nematodes were under scientific supervision. After all, the discovery is nothing short of a revolution in the field of cryobiosis and biology. Nematodes and other microscopic invertebrates, such as rotifers and tardigrades, are famously hardy, able to spend a long time in a desiccated or frozen state, and then return to life.

“But even their existing record for survival in suspended animation was only about 30-40 years,” says Anastasia Shatilovich, senior researcher at the Institute of Physical, Chemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science under the Russian Academy of Sciences. It was she, together with a cross-institutional group of scientists, who studied the ancient nematodes.

Initially, Shatilovich and colleagues did not look for nematodes in the permafrost. They studied communities of protists (unicellular eukaryotic organisms) that had survived thousands of years of cryopreservation in permafrost sediments in Yakutia. There is nothing intrinsically new or surprising about single-celled living objects that have existed in suspended animation for thousands and even millions of years. In 2000, researchers found and revived bacterial spores that had spent 250 million years in salt crystals.

Earlier, scientists from the Pushchino Scientific Center managed to grow a plant from viable cells found in seeds that had lain more than 30,000 years in the permafrost, but no one ever dreamed that multicellular worms could be resurrected.

“We hadn’t obtained multicellular animals that had survived cryobiosis on a geological time scale before. It was just a happy coincidence that we got two live nematodes in two soil samples at once,” Shatilovich says.

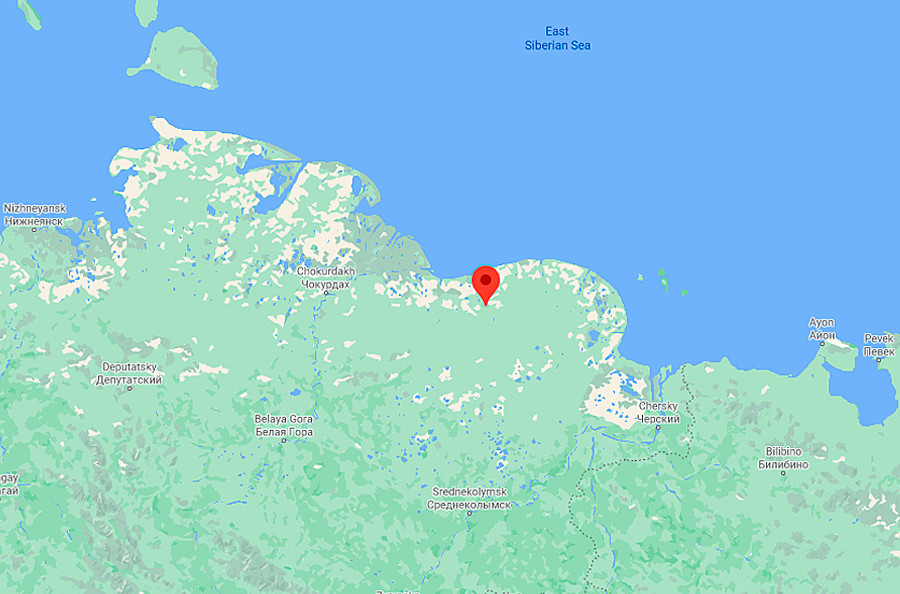

Alazeya River, Yakutia

Google MapsThe nematodes were not even noticed immediately. When the frozen soil samples were sent to the Pushchino laboratory, the scientists placed them in a Petri dish with a nutriculture medium and observed them every few days, expecting to find ancient protists. “We spotted the worms only when they started moving. That was about 10-14 days after unfreezing. They probably came to life even earlier,” she says.

Doubts that these were, in fact, more modern worms that slipped into the samples were dispelled, and here’s why. First, both samples in which they were found were selected by independent researchers from deposits of different genesis in different regions: near the Siberian rivers Kolyma and Alazeya. Second, one of the samples was taken from the drill hole using a high sterilization method.

One species of nematode, Panagrolaimus, was found in samples 32,000 years old. The second species, Plectus, turned up in an even older sample — 42,000 years. Both nematodes were identified as female.

Kolyma river

Google MapsAfter penning an article about it, the Russian team was contacted by scientists from Dresden offering to collaborate. As a result, the worm DNA was sent to Teymuras Kurzchalia and colleagues at Germany’s Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, where they are working on a complete decoding of the genome of the two nematodes.

The case of the nematodes, she says, was a stroke of luck, because if they had been revived from only one sample, scientists would have doubted the sterility of the selection — there is always the possibility of contamination. It all seemed too incredible.

“A single-celled organism can survive due to its adaptive properties, for example, the ability to form various stages of dormancy — spores or cysts. But a multicellular organism has a more complex structure. Although nematodes are also known to have a dormant stage (Dauer larva), during prolonged hibernation damage to DNA and cell membranes can occur and accumulate in the cells. Toxins can be produced that should either destroy the organism or be repaired during suspended animation or after defrosting. ... Somehow these worms managed to survive,” says Shatilovich, describing it as “a most curious enigma.”

Specialists of the Institute of Psychochemical and Biological Problems and Soil Science of the Moscow Region

https://issp.pbcras.ru/The full genome is set to provide answers to a whole list of fascinating questions. How do the damage repair processes work? What adaptive mechanisms did ancient worms have? What unique genes do they possess? Have the species evolved over 40,000 years? And others.

It took almost two years to decode — one per worm. As it turned out, one of the worms is a triploid, meaning that it has three sets of chromosomes and reproduces by parthenogenesis (monosexual reproduction). The German team plans to complete the decoding of the genome by the end of the year.

The descendants of these same nematodes are now in the collection of the Soil Cryology Laboratory, where Shatilovich works. Some of them are frozen, some dried, some alive and reproducing.

She admits to being often asked whether dangerous microorganisms could ever be thawed together with the nematodes. Might something terrible be released into the ecosystem?

“As a result of the ongoing thawing of the permafrost, organisms preserved in it find their way into the modern ecosystem every year, it’s a natural process.”

“We simply follow nature and do nothing that doesn’t happen in the natural environment,” says Shatilovich.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox