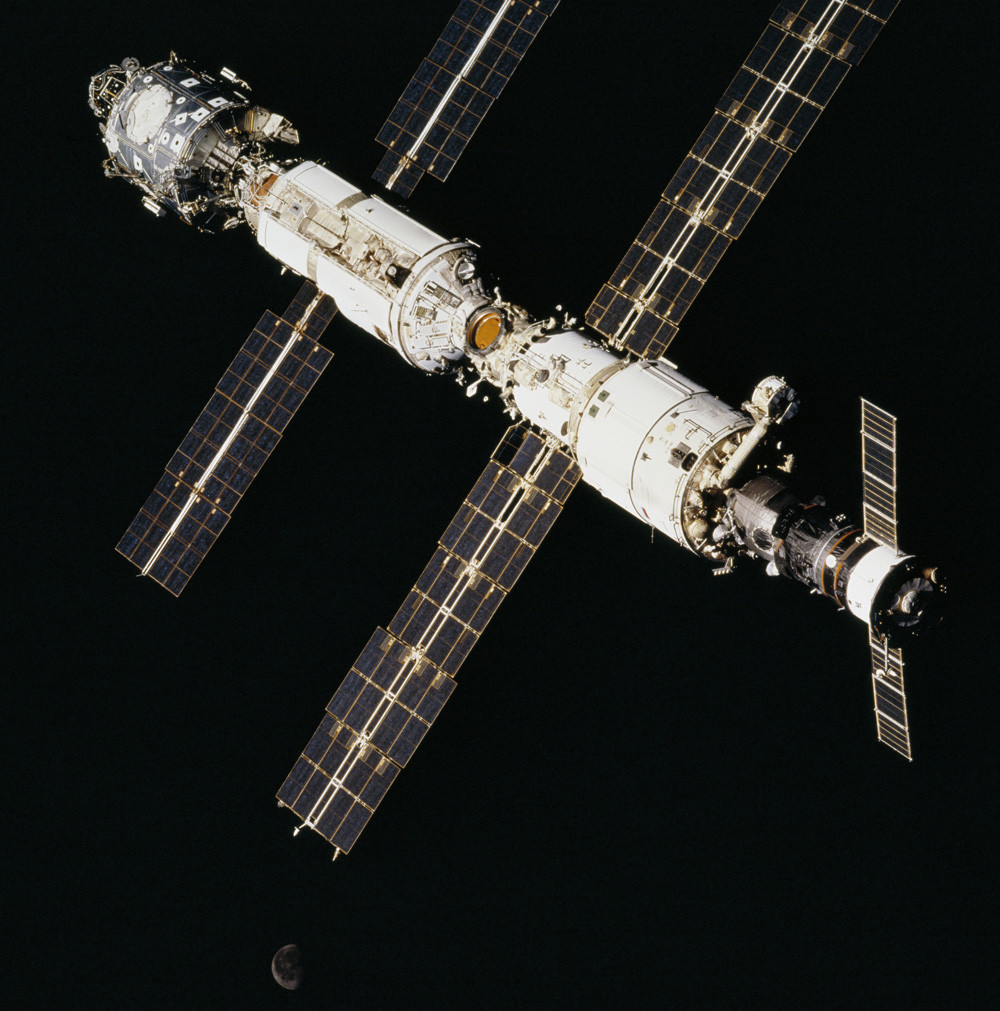

For the past 20 years, the ISS has been the only place allowing humans to stay in space for a lengthy period. It is located 400 km from the Earth and it has been a while since humankind ventured beyond that point. However, with its service life expiring in 2024, the ISS is growing obsolete and, on both sides of the Atlantic, voices are being heard that “humanity needs to move forward - to the Moon and Mars”.

In recent years, the ISS has been increasingly referred to as a financial burden. It claims some 30-40 percent of the participating countries’ space budgets. But the thing is that there is still no functioning alternative to the orbital station, while the number of problems experienced on the ISS continues to grow.

Over the past year, the technical condition of the ISS has deteriorated significantly. In August, a crack appeared in its hull, resulting in a drop in pressure at the station. At first, experts believed that the air leak was in the US segment of the station, but at the end of September, Roscosmos reported that the crack was in the Russian Zvezda module. This is a key module of the entire station: through its docking nodes, the ISS is refueled and replenished with drinking water. In addition, this module is responsible for adjusting the orbit (the ISS is the size of a football field and it needs constant help to stay in orbit).

At the time, the crack was covered with “improvised means” - American plasticine. However, this did not resolve the problem for good. In mid-October, the ISS crew found another possible crack in the Zvezda transfer tunnel: it was spotted with the help of a tea bag, whose movement in zero gravity was recorded by cameras. It is not yet clear whether there are any more cracks in the hull, but on December 19, the ISS was warned that they were running out of reserve air supply to compensate for the leak. Which means a threat to the safety of the crew.

So far, all this is consistent with a recent forecast by the Russian RSC Energia (a leading design corporation): “There are already a number of elements that have been seriously affected by damage and are going out of service. Many of them are not replaceable. After 2025, we predict an avalanche-like failure of numerous elements,” said deputy general director Vladimir Solovyev.

In particular, the Zvezda module itself cannot be replaced - its production has not survived perestroika, which means that it would have to be started from scratch, based on other technologies, and testing it would take a lot of time.

All this suggests one way out: to do with the ISS what is usually done to massive space objects whose service life is over, i.e. to sink it in the Pacific Ocean, away from navigation routes. A space object partially burns up in the atmosphere and its debris drops into the water. This is, for example, how its predecessor, the Russian station Mir, was deorbited in 2001.

For the U.S., the question of injecting more money into the maintenance of an outdated station is particularly acute, as it bears about 70 percent of its costs (compared with Russia’s 12 percent). Every time, extending the service life of the station by another year freezes billions of dollars that could go towards creating a new station and developing other projects. NASA has already announced that it will stop funding the ISS from 2025 to “free up” this amount. Russia, on the other hand, is unequivocally in favor of extending the operation of the station until 2028 or 2030. Although no-one has yet come to the decision as to the future fate of the ISS, it looks like the participating countries are interested in extending the station’s life (but probably on slightly different conditions).

“The main reason for this interest is that none of the program participants have any replacement for the ISS,” says Vitaly Yegorov, an independent expert and space writer.

In June 2019, NASA presented the LEO program, opening the ISS to commercial business. After all, if the agency stops paying billions to maintain the station, someone else has to do it. The program promotes private astronaut missions to the ISS, funded by private companies, and the construction of private space stations.

For Roscosmos, a similar option has never been considered seriously. Firstly, there is no private space sector in Russia, all space programs are run only by the state. Secondly, as industrial expert Leonid Khazanov points out, over the years, the ISS has mostly been used for research into extraterrestrial space and for science. This is its main purpose and experiments and scientific programs on board the station are conducted every day. “These experiments are possible only if there is government funding,” he says.

Hence, it follows that it is only the American modules of the station that may be put up for sale, while the Russian one will remain state-owned. Furthermore, even if a buyer is found, there is one significant problem: the Zarya docking compartment, which was made in Russia, was in fact paid for by NASA in the 1990s, as part of an informal American program to support Russian cosmonautics and therefore belongs to NASA. “Russia will have to build a new docking compartment in order to have access to its own modules. And without a docking compartment, no private owner will want the ISS,” Yegorov says.

Another option is to transform the ISS into a hub for delivering cargoes to the Moon. An orbital lunar station is only a matter of time, its various options (including joint development) are being considered by many countries and the ISS could serve as a “staging post”, which would be cheaper than flying rockets directly to the Moon.

In this case, there are many more players who may want to operate the ISS in this capacity: lunar programs (or, at least, ambitions) are entertained by both space agencies and private entities, like SpaceX, Boeing and Russia’s S7. For example, Roscosmos was planning, among other things, to send parts of the Russian segment of the ISS to the Moon by 2030, in order to build a lunar orbital base from them. That said, this plan has been met with much scepticism and so far does not have a very realistic timeframe. It would appear that for the time being Russia is more interested in preserving the ISS in its current form.

Another option, which has been discussed much more often, is to separate the Russian segment of the station and continue using this multi-module bit of the ISS independently. Once the agreement on the joint operation of the ISS expires in 2024, the participating countries will have their hands untied and could “go it alone”. However, for Russia this outcome, albeit tempting, is much more complicated than all the previous ones. It implies a multiplication of technical, as well as financial problems.

For example, the key Russian module, Zvezda, which requires orientation and orbit adjustment, does not have its own control moment gyroscopes (special rotors used for altitude control). Russian Progress cargo spacecraft, which are docked to the aft port of the module, sometimes turn their engines on to raise its orbit. However, if the engines are used all the time, fuel will quickly run out. Yegorov points out that the combination of American control moment gyroscopes and Russian attitude control engines is one of the key elements of the “marriage contract”, which makes a “divorce” of the two segments into two separate stations impossible.

Furthermore, the station’s wear and tear and cracks will not go anywhere, so they too will need to be addressed. At the same time, the Russian space sector, which is already heavily subsidized from the budget, is losing more and more money. After the successful launch of Elon Musk’s Crew Dragon, the line of those wishing to buy a seat on a Soyuz rocket is getting dangerously short, while commercial cargo launches, too, have taken a hit since 2012, when SpaceX launched its heavy rocket Falcon 9. In the meantime, the Russian Ministry of Finance has suggested that Roscosmos’s funding for the next three years should be cut by another 60 billion rubles.

The option that has so far been getting the most prominence is the idea of building Russia’s own national station to replace the ISS - the Russian Orbital Service Station (ROSS). It has the backing of Roscosmos head Dmitry Rogozin himself: “The ISS will probably last until 2030. We are now starting to create a new orbital station, we already have two modules in reserve. <...> We plan to add a few more modules to it: in effect, after 2030, the Russian Federation will be a country that will create a new station.”

According to him, the new station, unlike the ISS, will be able to refuel ships and satellites, thus increasing their service life. It is also planned to house a workshop for assembling spacecraft that will fly to the Moon, Mars and asteroids and a headquarters for controlling the entire orbital group. One of the modules will be commercial, it will be able to accommodate four tourists and will have two large windows and Wi-Fi. It is being said that all the modules for the ROSS may be launched into orbit with Angara-A5 launch vehicles. In December 2020, Russia carried out its second successful test of the rocket in six years, while the rocket itself had taken a quarter of a century to develop.

Perhaps the key advantage of the ROSS is its unlimited service life, thanks to the use of replaceable modules. However, Russian experts note that the ROSS, albeit good as an idea, may remain just that, an idea. “Russian plans change very often, so I would not say for sure that after the ISS Russia will build its own station,” says engineer Alexander Shayenko, who developed the Angara-A5 and KSLV launch vehicles.

Indeed, there are plenty of examples of unfinished projects in the Russian space program. Take, for instance, the Nauka module, which was supposed to become a scientific module in the Russian segment of the ISS. It was planned to be launched into orbit 11 years ago, but it never happened.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox