Just over 10 years ago, Russian scientists drilled a borehole to the relict Lake Vostok in Antarctica, which had been completely isolated from the outside world for millions of years. Vostok is an enormous subglacial lake comparable in size to the state of Qatar. Until the 1990s, no one was 100 percent sure it existed.

It has been described as the last big geographical discovery that will ever be made on Earth and also as the key to "unlocking" the mystery of whether there is life on Jupiter's moon, Europa. A subglacial ocean lies under the thick ice shell of this celestial body that could provide a habitat for organisms similar to those that might exist in Lake Vostok – organisms resistant to very extreme conditions.

And scientists really did manage to find something…

The area began to be explored for the first time in 1957, when a Soviet expedition went there. The scientists traveled using a special sled-train, capable of negotiating the snow-covered plains of the glacier.

Scientists then set up the first research station, Vostok – after which the lake was later named – in the center of the continent. The station essentially existed in complete isolation from the outside world – the nearest coast was 1,260 km away and the nearest research station 1,410 km away. And the Pole of Cold, where the lowest temperature on Earth of minus 89.2 degrees Celsius has been recorded, is also located there.

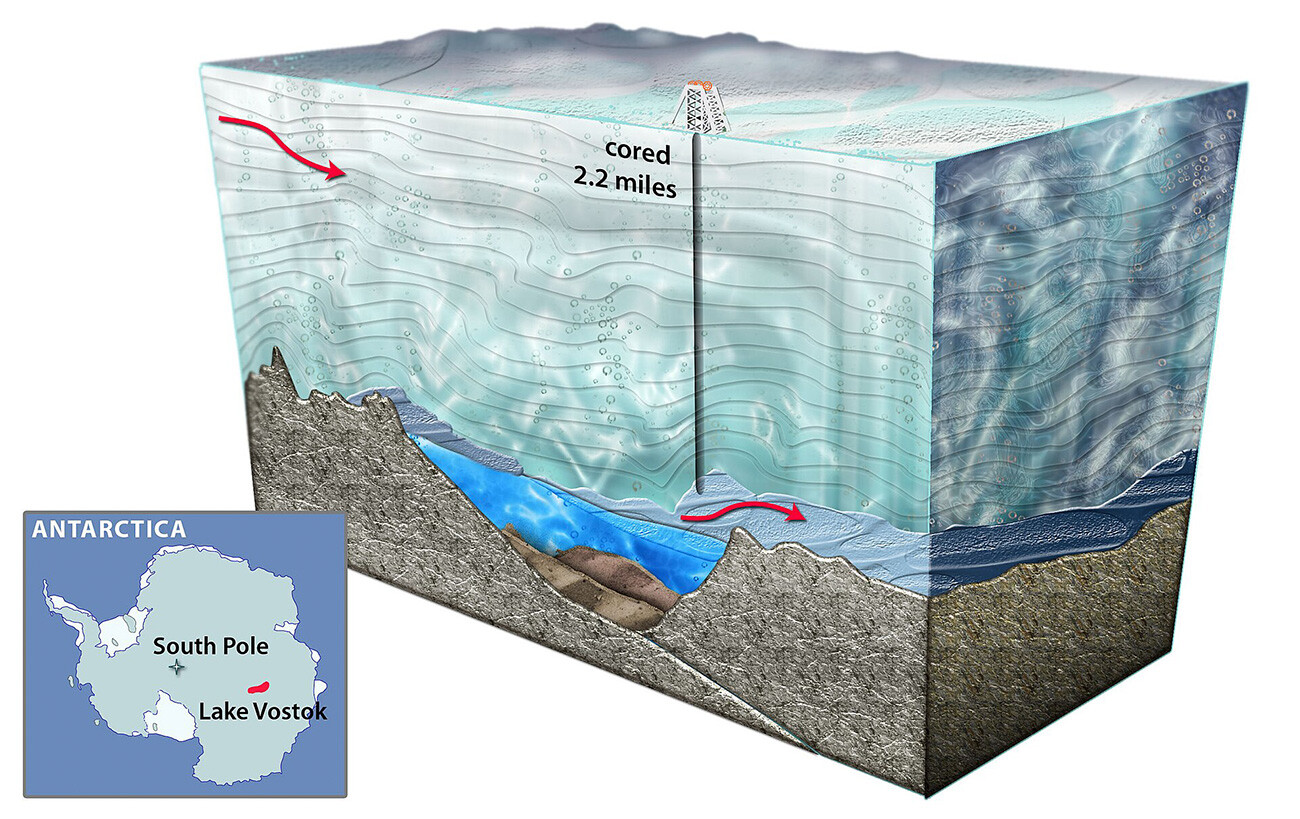

After setting up the station, in the 1960s, polar explorers began to drill into the glacier. Admittedly, their goals were not as ambitious as searching for the most ancient lakes on Earth. The scientists wanted to get a so-called ice core – a column of ice of the sort usually obtained from the depths of glaciers. Bubbles of trapped air and more solid particles often accumulate inside them and this makes it possible to take a closer look at the atmosphere and soil composition of the Earth from millions of years ago. For this reason, the Vostok Station is currently regarded as one of the main sources of information about the ancient climate of the planet.

Initially, it was planned to use thermal drill heads, but it only proved possible to reach a depth of 50 meters with them. A plan using nuclear drills was also considered. The scientists wanted to use a nuclear reactor to melt all the ice to the required depth, but the project was abandoned, due to its high risk. The drilling eventually began in earnest in the late 1960s, when specialists from the Leningrad Mining Institute arrived in the Antarctic. They drilled the first, 560-meter-deep hole in the ice.

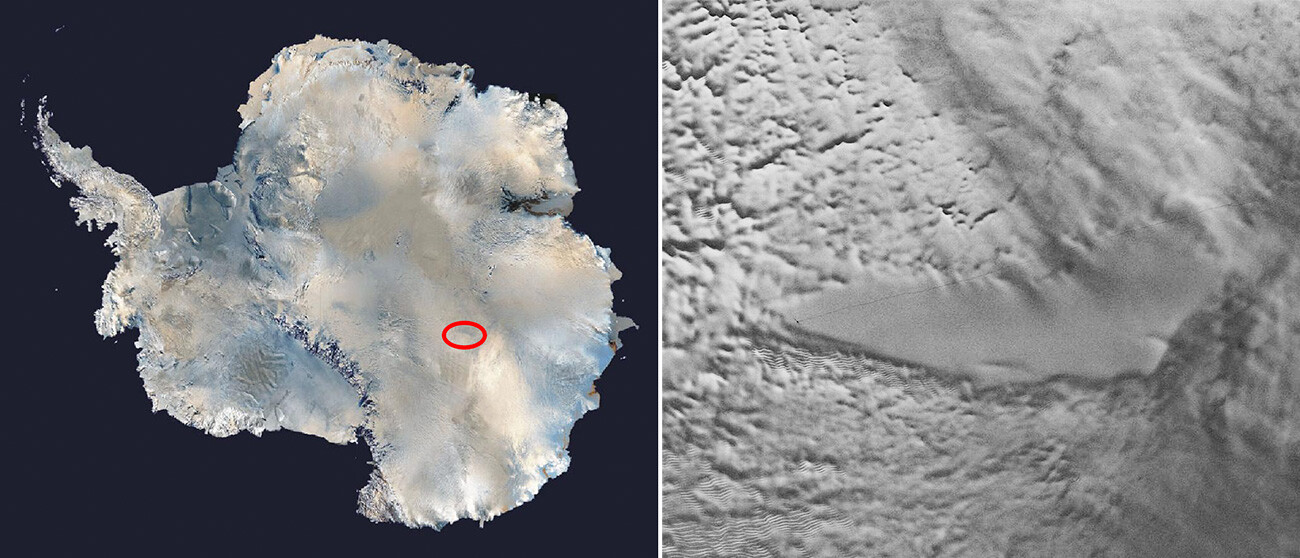

The existence of a subglacial lake there was first seriously considered in the 1970s. British colleagues were scanning the glacier in the exact location of the Soviet station and registered a so-called "flat" return signal from under the ice. They put forward the hypothesis that it could indicate a boundary between water and ice, which meant that something really did lie somewhere deep inside the glacier.

But, a real breakthrough in the study of Antarctica's underground lakes was achieved in 1996 by Russian researchers Andrey Kapitsa and Igor Zotikov from the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Geography. Alongside British scientists, they compiled all the data from radar and satellite observations of the area and reached the definitive conclusion that, at a depth of around four kilometers, a gigantic glacial lake had lain concealed from mankind for millions of years. It had an area of 15,690 sq. km and an average depth of 432 m (1,417 ft).

By the time of this discovery, a borehole 3,100 meters deep had already been drilled under the Vostok station. The lake was now just 130 meters away.

The scientists were forced to cease drilling, however, and to mothball the borehole. The problem was that a particular chemical mixture was being used to melt the ice. Consisting of kerosene and freon, it did not freeze at the extreme Antarctic temperatures and enabled the pressure of the ice crust to be held in check in the course of deep drilling. Freon had, by then, already been recognized as a substance harmful to the atmosphere and was subsequently banned. Aside from that, researchers feared that toxic chemicals entering the water were in danger of not merely spoiling the results of their research into the underground lake, but also destroying any life that could have existed there in the course of 14 million years of isolation.

So, the scientists now faced the task of devising a drilling method that was less dangerous for the ecosystem. Another eight years were devoted to these scientific investigations.

Work to obtain water samples was only resumed in 2006, but, even with the new methods, the participants in the Antarctic expedition were still unable to drill all the way down to the coveted lake: They were dogged by either technical breakdowns or erratic financing. Because of this, the scientists only managed to reach the actual lake on February 5, 2012. But, then, the borehole was immediately shut down, due to lack of funds.

A second operation to probe the lake was carried out in 2015 – and, this time, the attempt finally produced results. Forty-nine DNA sequences of various organisms were discovered in the samples, the majority of which, admittedly, were from the surface of the planet, while just two attracted real interest from biologists.

One of the samples resembled an aquatic bacterium that should, in theory, mainly inhabit marshy soil and definitely not glacial waters under high pressure and at extremely low temperatures.

The other sample was completely unfamiliar to scientists and its genome had an 86 percent similarity to known species. "If we had unveiled the DNA of the organism whose discovery we confirmed in 2016 without announcing where it was from… we would have been asked whether it was from Planet Earth at all," says Sergei Bulat, who was in charge of work to study the water samples from Lake Vostok.

The research subsequently fizzled out, however. Further funding for exploring deeper levels of Lake Vostok subsequently stopped being allocated on the grounds of a change of policy: Priority was now to be given to the North Pole. However, Sergei Bulat continues to study the samples obtained earlier.

In 2018, he discovered another dweller of Lake Vostok – the bacterium (bacillus) Marinilactibacillus sp. These bacilli feed on organic matter, which is practically absent in the waters of Lake Vostok, so there could well be nutrient-rich locations at greater depths.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox