Gorodki: Ancient Russian game enjoys renaissance

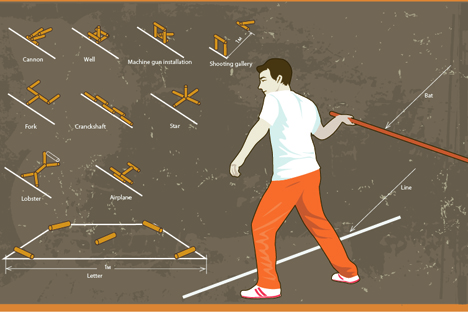

The game consists of throwing a bat from a predetermined distance at the gorodki, which are arranged in one of 15 configurations. Source: ITAR-TASS

The gorodki player gets ready to throw. The wooden bat in his hand looks just like a normal stick. The playing area in front of him is lined with pins set out in bizarre shapes.

He throws the bat… a clatter, and some of the pins end up behind the line of the square drawn out on the ground.

To understand gorodki, you first need to know the terminology: The word gorod means "city," while gorodok means "small town" or "village."

The aim of the game is to knock the five cylindrical pins, or "villages," out of the "city" (that’s what the square-shaped playing area is called) in as few throws as possible.

The "villages" are 20 centimeters long and about 4.5–5 centimeters in diameter. Players stand 13 meters – a "con" – from the "city" and throw the stick.

If they successfully knock one or more of the pins out of the "city," then they continue to throw from a distance of 6.5 meters ("half a con").

A village is considered "banished" when all the shapes have been knocked out of the square-shaped playing area.

The shapes are arranged into configurations with names such as "cannon," "fork," "star," "crawfish" and "airplane."

The player who uses the least amount of throws to knock out all 15 shapes over the course of three rounds wins. Gorodki can be played one-on-one or in teams.

Click to enlarge the infographics

In gorodki, the playing area is a 2 by 2 meter square divided into zones where the players aim their shots.

The bats used by the players to break up the figures are usually made from oak, hawthorn or dogwood, and they cannot be longer than one meter.

Players receive no points, have the villages re-set and are charged a turn if the bat touches the line or the ground in front of the line; if they step on or over the boundary line; and if they do not throw the bat within the designated 30-second time limit.

The famous Russian military leader, Alexander Suvorov, once compared gorodki with the tactics of warfare: “Setting up your throw sharpens your aim; striking the pins makes you swift in attack; knocking the pins down develops your force.”

Gorodki was invented by Russian peasant farmers, who would etch out a playing area in the ground and then knock wooden figures down with bats made from the very same wood.

Concrete and asphalt playing areas didn’t appear until much later, in the 20th century, by which time the bats already had iron sections on them.

In 1928, gorodki was included in the All Union Olympics. And the official rules, which still govern the sport today, were finalized in 1933. The number of configurations was fixed at 15.

The 1960s and 1970s were the golden years of gorodki in the Soviet Union. Every stadium, vacation retreat, health spa, courtyard, summer camp, plant and factory had its own gorodki playing area.

But interest in the sport began to wane, until the 1990s, when it experienced a revival of sorts. The International Federation of Gorodki Sport was established, with Belarus, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Moldova, Russia, Sweden and Ukraine as its members.

Many famous people have tried their hand at gorodki over the years, including writers Leo Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov, Soviet leaders Lenin and Stalin, scientist Ivan Pavlov and singer Feodor Chaliapin.

President Vladimir Putin, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin and Russian Minister of Sport Vitaly Mutko have all been caught playing gorodki themselves.

At a meeting with the members of the Council for Interethnic Relations in February 2013, Vladimir Putin even announced that Russia “should work toward getting our national sports included in the Olympic program.”

Unfortunately, not every Russian city has a place to play gorodki or coaches to guide young talent. And the fact is that many people simply do not know that such a game even exists.

Anna Tomashevich coaches the Nizhny Novgorod women’s gorodki team. She laments the continuing low popularity of the sport in Russia: “We don’t have the money to make the sport popular, to let the people know that gorodki is still alive and well.”

Practically every gorodki player today came to the sport thanks to friends or relatives. Priozersk player, Daniil Mayerovsky, first tried his hand at chucking the bat when he went to one of his friend’s training sessions.

He started turning up regularly and became hooked: “I fell in love with the game straight away. I’ve made lots of new friends here. And it’s a sport, after all, a form of physical exercise that improves your health and makes you stronger.”

It was chance that brought Tomashevich to gorodki as well.

She was coaxed into getting involved by her brother: “It was a male-dominated sport back then – I was the only girl at the stadium. That’s when I started playing. You might say it was love at first sight. Gorodki is considered a man’s game, and I guess that’s what drew me to it – I wanted to play on the same level as the guys, to prove to them that girls can play gorodki too.”

It’s not just professional coaches that are trying to get the word out about gorodki; ordinary people are getting involved as well.

Marina Tolstykh has been organizing children’s tournaments in Novosibirsk: “I just want to get kids playing the game and having fun. Gorodki is so much better for them than computer games and the Internet, and kids today don’t seem to be interested in anything else. Gorodki teaches kids about friendship and respect for your opponent.”

Gorodki is never likely to pose a threat to soccer or tennis in terms of global popularity, but its support base is growing at a steady pace.

Gorodki playing areas will be appearing all over Moscow this summer, with the first one opening at Bauman Gardens on May 18th.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox