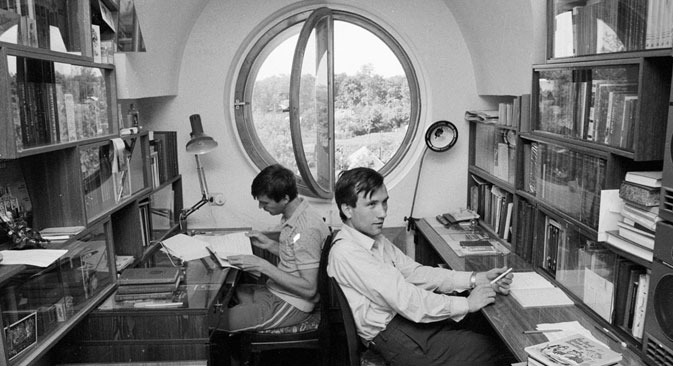

Shared space: communal living was a social phenomenon of the Soviet era. It denied privacy and sought to create relationships suited to the ideology of the state. Source: RIA Novosti

The architecture of Soviet times is not just a monument to the epoch, but also an illustration of the social ideals of the Kremlin’s former leaders. Even the names of the buildings are testimony to that, formed as they are from the names of the leaders: Stalinki, Khrushchyovki and Brezhnevki.The history of Soviet communal living is contained within their walls.

The Stalinki are Stalinist apartment blocks that housed the elite. They were built from the end of the Thirties to the mid-Fifties, predominantly in the neo-classical style, and their principal characteristic was a sense of space and enormous size. They featured high ceilings of up to 3.2 metres (10ft 6in), wide window sills and thick walls. But behind the grand facade lurked room partitions made from poor-grade materials that have deteriorated over time, as well as wooden overhangs between storeys. In most cases these apartments had three or four rooms.

Homes for the elite

There were two types of Stalinki: those for the upper levels of Soviet society and those for the workers. The first were known as nomenklatura. Soviet and economic leaders, high-ranking military officers, those who worked in the security agencies as well as powerful representatives of the technical and creative intelligentsia lived in these apartments. They were well planned, with many featuring study rooms, nurseries and libraries as well as servants’ quarters, spacious kitchens and separate bathrooms. Rooms ranged from 15 to 30 square metres.

'Stalinki' were well planned, with many featuring study rooms, nurseries and libraries as well as servants’ quarters, spacious kitchens and separate bathrooms. Source: RIA Novosti

The directors’(direktorskiye) apartments featured classical architecture and simple decor. The buildings were large, with a high first-floor balcony and decorated with elaborate plasterwork and mouldings. They were either built in the centre of a city or lined city squares, and have become tourist attractions in a number of urban centres.

Apartment blocks intended for communal housing were built more simply. Several families would live in a single apartment, or kommunalka, and share lavatory, bathroom and kitchen facilities. These apartments were smaller and often featured interconnecting rooms. In some cases there were no bathrooms in the corridor-type apartments constructed after the war.

There was nothing extravagant about the architecture, and the facades were almost plain or had standard moulded decor. This sort of Stalinki was constructed in workers’ villages, near factories or in residential quarters. These apartment blocks represented the divisions in society. Behind the propaganda about equality was the reality of a society divided into two distinct categories.

Decor not on the agenda

After 1956, fewer and fewer of these blocks were built. Nikita Khrushchev, who succeeded Joseph Stalin, shifted the emphasis on to mass production and the last Stalinki were built without internal decor. Then came the Khrushchyovka era. In everyday life the Stalinka and Khrushchyovka have become bywords for a luxury lifestyle for the elite and a cheap, uncomfortable one for others.

The Khrushchyovki were three- to five-storey apartment blocks with small apartments. The first designs featured brick and slate roofs but were later given plain bitumen roofs with a very small loft space to save money. Later apartment blocks were made in sections in a factory and assembled on site without taking the surrounding architecture and landscape into consideration.

The expected life of the blocks was just 25 years but a great many are still in use. The Moscow authorities have promised to demolish all the Khrushchyovki and to replace them with contemporary structures of greater quality. When housing prices are high, the Khrushchyovki are more or less affordable, but the cost is similar to that of apartment blocks in many European cities.

"Low rates of individual design/construction and high costs didn't allow solving the housing needs of grown cities," - says Alexander Strelnikov, urbanist, a member of Scientific city-planning institute. "Therefore Nikita Khrushchev set architects a social task – to develop housing projects of moderate quality and the main thing being to pass from facades to quarters."

"It then shifted the movement of communal flat inhabitants into separate apartments. Good work, but the decrease in quality from grandiose to the ascetic generated scornful nicknames - «storied apartment blocks" and even "rich house". What costs the standard of settlement of 9 sq.m per person and the height of a ceiling of 2,5 m! I saw a similar one-room apartment with a living space of 9 sq.m. It required lifting a table in order to sit down on a sofa bed," adds Stralnikov.

Lookalike cities

Despite their many drawbacks, these apartments represented the most desirable accommodation in Soviet times. People moved there from the kommunalka and the small kitchens, low ceilings, and poor sound-proofing were accepted because one family lived in each apartment.

The first district built entirely of these structures was Cheremushki in Moscow, and the exercise was repeated across the country. These apartments were so alike that, even today, if you are in one of these districts it is difficult to tell which city you are in. These apartment blocks continued to be built in Russia until 1985.

Brezhnev aims higher

Finally came the Brezhnevki, named after the next leader, Leonid Brezhnev, which were high-rise blocks of nine to 17 storeys. The quality of construction was a little better but they were essentially a magnified version of an uncomfortable living space and turned cities into faceless uniform expanses.

Although these building conventions were swept aside with the Soviet Union, it would seem that today’s architects, while given more freedom, are not ready to abandon the characterless apartment block just yet.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox