In the mid-19th century, when the Chinese and later the Russians appeared in present-day Primorsky Territory, these lands were inhabited by among others, the Nanai, Udege and Oroch peoples. An outcome of this interaction is the Tazy people, a group that resulted from mixed marriages between the Chinese and native peoples of the area. Today just 276 people identify with this group.

Back then native peoples were called “inorodtsy” (meaning non-Russian), whereas now they are usually identified as the indigenous peoples of the Far East. However, in Russian they are also sometimes referred to as the small peoples of the Amur Region (malye narody), although this refers to the number of representatives of the group and not their physical size or importance.

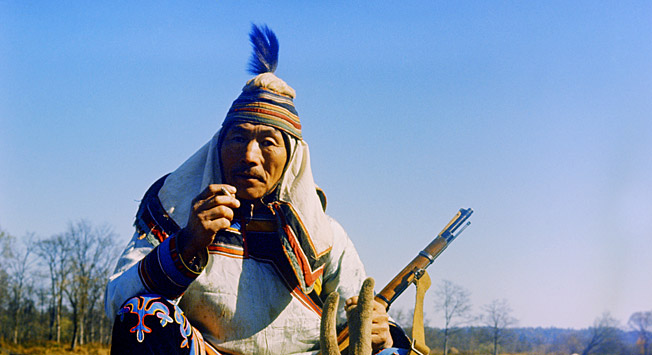

Photo credit: TASS/Yuri Muravin

Scholars place these peoples as belonging to the Tunguso-Manchurian language group. Some became urbanized long ago, while others still live in the taiga. The primary occupations of indigenous residents of the taiga here are hunting and fishing, as they have been for many centuries.

When the Russians encountered them, they were impressed by their mastery of archery for hunting, harpoons for fishing and their craftsmanship of wooden boats, which they used to traverse the rivers. A small boat was called “omorochka,” while one able to carry more than one person was called “bata.” Their clothes were sown using animal and even fish skin.

Photo credit: TASS/Yuri Muravin

In the 19th century the area’s indigenous people began trading with the Chinese and Russians: they sold the latter fur in exchange for weapons and powder. However, along with this contact came opium, alcohol and smallpox, which came to plague the taiga.

The life of the native peoples of Primorye was the subject of the writings of Vladimir Arseniev, a scholar, writer and explorer who authored the book “Dersu Uzala,” named after his Nanai friend and guide. A Soviet-Japanese production based on this book was shot in 1975 by Akira Kurosawa and won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

Arseniev characterized the native inhabitants of Primorye as “primitive communists.” He argued that their lifestyle and their relations to each other and to the world were fairer and more natural than European mores. Native peoples believed that everything was a living thing. Dersu used to call all things “people,” including animals, the Sun and fire. Indigenous peoples in the Primorye region also had a well-developed sense of ecological awareness.

Today there are few natives left in the Primorye region numbering just 1,500-2,000 people. They live mostly in the northern parts of the territory in the Terneysky, Krasnoarmeisky and Pozharsky districts. The taiga there remains largely untouched and undeveloped and still has large populations of elk, Siberian deer, bears and tigers.

Although there are very few native speakers of the Udege language left, many Udege still lead a traditional way of life. The most well known indigenous settlements are Krasny Yar, with about 600 residents, and Azgu, with a population of about 200. While these villages are difficult to reach, Krasny Yar hosts an annual festival of Udege culture that manages to attract visitors from Japan, Korea and other countries.

Photo credit: TASS/Yuri Muravin

You can get to know more about the everyday life of the contemporary Udege through the film “The Forest People” (Lesnye lyudi). Released in 2012, this film by Vasily Solkin and Gennady Shalikov was shot through a partnership between a Vladivostok television station and the Zov Taigi environmental group:

The Udege Legend National Park, set up in the Krasnoarmeisky District of Primorye Region offers insights into life in the taiga with the aim of developing ecological and ethnographic tourism in the area. The entrance to the national park is located in the village of Roshchino, which can be reached by bus or car from Vladivostok or Khabarovsk.

In the north part of Primorye still another national park is being developed. It is called Bikin Park and is located in the Pozharsky District. Its establishment has caused some concern among the indigenous peoples of Primorye.

Photo credit: TASS/Yuri Muravin

The purported goal of the park is to save the “Russian Amazon,” as the media often calls the Bikin River, from deforestation. However, the Udege from Krasny Yar fear that their traditional way of life will be restricted. In Russia indigenous peoples enjoy special rights regarding hunting and fishing, as these have long been a means of subsistence for them and part of their way of life.

The authorities maintain that the interests of the native inhabitants of the region will be taken into consideration and that they will still have the ability to gather firewood, nuts and berries, hunt sables and fish. The Primorye administration has promised that Bikin will be the first national park in Russia to be directly administered by a native community.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox