Still standing tall: Russia’s incredible Ryazan kremlin

Ryazan Kremlin, south view. Background: Cathedral bell tower, Dormition Cathedral. Foreground: wall of Transfiguration Monastery with West Gate&Church of St. John, Transfiguration Cathedral (right). Aug. 28, 2005.

William BrumfieldAt the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian chemist and photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for vivid color photography (see box text below). His vision of photography as a form of education and enlightenment was demonstrated with special clarity through his images of architectural monuments in the historic sites throughout the Russian heartland.

In summer 1910, Prokudin-Gorsky made a series of journeys along the Oka River, a major tributary of the Volga. During these trips, he took numerous photographs in Ryazan, 190 km southeast of Moscow. My photographs of the town were taken over an extended period from 1984-2006.

Ryazan Kremlin. Background: Dormition Cathedral. Foreground: wall of Transfiguration Monastery, Transfiguration Cathedral (far right). Summer 1912.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyAt the time of Prokudin-Gorsky’s visit, Ryazan had a population of around 45,000. Today it is a growing city with a population of over half a million. Known for its historic monuments, the Ryazan

A turbulent history

Few of the ancient cities of the Russian heartland have endured a more turbulent history than Ryazan. Already an important town in the 11th century, by the middle of the 12th century Ryazan had become the center of a major principality that held sway over

Ryazan Kremlin, northwest view. From left: Archbishop's Palace, Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, Dormition Cathedral, Epiphany Church, Transfiguration Cathedral, bell tower. Summer 1912.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyIn 1237, Ryazan was devastated by the Mongols, and attempts to re-establish settlements in the immediate area were undercut by Tatar raids over the following decades. By the 14th century, the local church and political leadership decided to re-establish Ryazan at the better-defended settlement of Pereyaslavl, 55 km northwest at the point where the small Trubezh River empties into the Oka.

For centuries, the town was known as Pereyaslavl-Ryazansky. By the beginning of the 15th century, Pereyaslavl-Ryazansky had a large fortress (kremlin) whose earthen ramparts are well preserved. Prokudin-Gorsky and I both photographed the

Ryazan Kremlin, northwest view. From left: Church of Holy Spirit, Archbishop's Palace, Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, Archangel Cathedral, Dormition Cathedral, Epiphany Church, Transfiguration Cathedral, bell tower. May 13, 1984.

William BrumfieldAlthough the threat of Tatar raids eventually waned, the region was afflicted by famine and disease at the end of the 16th century and wracked by violent disorders in the early 17th century during the dynastic interregnum known as the Time of Troubles. In 1778, the town was designated simply Ryazan.

A cathedral’s construction, collapse and resurrection

The city's greatest monument is the Cathedral of the Dormition, whose name derived from the

Ryazan Kremlin. Dormition Cathedral, west facade. Summer 1912.

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyAfter the initial debacle, the project was entrusted by the next metropolitan, Avraamy (who served from 1687 to 1700), to the renowned architect Yakov Bukhvostov. Like his hapless predecessors, Bukhvostov faced serious challenges with the foundations and the roof vaulting for the immense structure. He was also involved in other projects at the time and faced court litigation on one of them. Nonetheless, with the assistance of local master builders, the structure was completed in 1699. Another three years were spent on its interior, including the construction of a large icon screen. In August 1702, the cathedral was consecrated by a third metropolitan, Stefan Yavorsky (1658-1722), who became one of the leading prelates of the Russian Church during Peter the Great’s reign.

But the travails of the building were not over. Thanks to its exposed location and height, the roof and cupolas, as well as the upper windows, were frequently damaged. The structure itself seemed under threat because of leakage and resulting cracks in the walls. In 1800, the Holy Synod in St. Petersburg issued a directive stating that the structure should be demolished and rebuilt.

Ryazan Kremlin. Dormition Cathedral, west facade. May 13, 1984.

William BrumfieldFortunately, Metropolitan Simon of Ryazan (bishop from 1778 to 1804) decided to consult with the local council and, with the support of wealthy merchants, marshaled the resources to undertake fundamental repairs. Russia’s architectural heritage benefited immeasurably from the wisdom and diplomacy of an experienced bishop. Alas, Simon died in January 1804, a few months before the reconsecration of the cathedral in August.

A unique building

The Ryazan Dormition Cathedral represents one of the most distinctive designs in the history of Russian church architecture. Over 40 meters tall with five large drums and cupolas as well as extensive window space, the structure is balanced on a complex system of cellar vaults, which also support a terrace platform for the cathedral. The cathedral's roofline was designed as a horizontal cornice with decorative brick patterns.

Ryazan Kremlin. Dormition Cathedral, north facade. Carved limestone columns. Summer 1912.

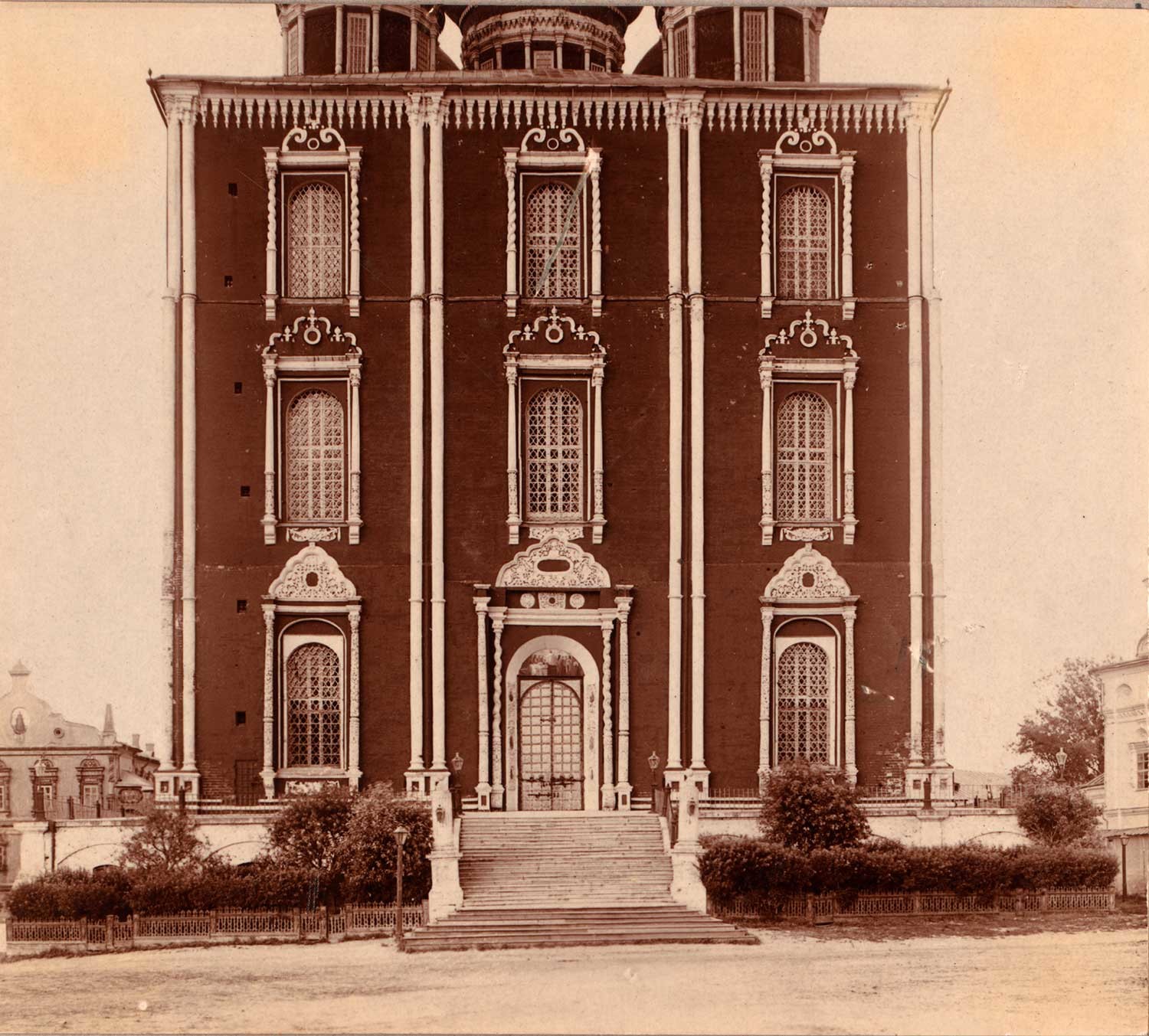

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyThe tall windows were framed with carved limestone columns and pediments. The 5,000 blocks comprising the limestone details were standardized, thus enabling the architect to complete the structure within six years, a relatively short period in view of the complexity of the project. Although preserved only in a contact print, Prokudin-Gorsky’s direct frontal view from the west conveys with striking clarity the segmented facade design.

Ryazan Kremlin. Dormition Cathedral, west facade with main portal. May 13, 1984.

William BrumfieldThe window surrounds and the paired brick columns (painted white) that vertically divide the brick facades provide a palatial ambience to one of the largest churches of the 17th century - larger, in fact, than the Dormition Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin. Prokudin-Gorsky’s detailed photographs and mine convey the vivid contrast between the white ornamental trim and the red brick background.

Ryazan Kremlin. Dormition Cathedral, west facade. Main portal. May 13, 1984.

William BrumfieldClosed in 1929, the Dormition Cathedral was used for archival storage and in the 1960s began to function as a museum. Services resumed in 1993, and in 2008 the cathedral was formally returned to the Ryazan Diocese.

To the west of the cathedral at the edge of the kremlin stands the enormous bell tower, built over a half-century from 1789 to 1840. At least three architects were involved in its construction, including Andrey Voronikhin, one of the major architects of St. Petersburg at the beginning of the 19th century. Prokudin-Gorsky’s contact print - and my photographs - give an idea of the scale of the bell tower in relation to other kremlin structures. The contrast between the Neoclassical bell tower and the decorative mannerism of the Dormition Cathedral provides an exemplary view of the dramatic changes in Russian architecture over the long 18th century.

Ryazan Kremlin. Dormition Cathedral, east view. August 28, 2005.

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century the Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France with a large part of his collection of glass negatives. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. Many Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles will juxtapose Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox