One day in December 1916, Grigori Rasputin, a confidante of the last Russian emperor, ate a cake with potassium cyanide and washed it down with tainted Madeira. The mystic had no idea that he was being poisoned, but for some reason the poison did not work. Four subsequent gun shots also failed to kill him. Rasputin met his end only at the bottom of the Neva River, where the assassins dumped his body that was wrapped in heavy chains. This bizarre and grisly crime drama unfolded in the splendid Yusupov Palace.

The Yusupov Palace is a bright, yellow three-story 18th century building on the Moika River embankment in downtown St. Petersburg. Construction on the Neo-classical palace began in the 1770s, and it was intended for use by Andrei Shuvalov, a privy councilor to the court of Catherine the Great.

Designed by the famous French architect Jean-Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe, who is also known for building Gostiny Dvor, the Academy of Arts and the Small Hermitage, the palace was bought in 1830 by one of the richest men in Russia, the manager of the imperial court, Prince Boris Nikolayevich Yusupov. The palace became the 57th property to be owned by this family; for example, they had another magnificent palace in Crimea.

The Yusupov family descended from the ruler of the Nogai Horde, and in terms of nobility it was practically equal to the Romanovs. In terms of wealth, however, the Yusupovs even exceeded them. The first Yusupovs arrived in Moscow during the time of Ivan the Terrible, and subsequent tsars rewarded their descendants with rich lands and princely titles. The Yusupov fortune was further enhanced by the advantageous marriage of the first Yusupov to a rich widow, Katerina Sumarokova, who was the daughter of an official close to the imperial court.

In addition to the palace, there was a family chapel dedicated to the Protection of the Mother of God, horse stables and a garden, as well as a private theater in a baroque wing added to the palace in the 1830s. This gorgeous theater is not unlike a smaller version of the famous nearby Mariinsky Theater. The Yusupovs held splendid parties in their palace, with St. Petersburg's finest ballet dancers and the most renowned orchestras performing on the stage of their home theater.

Design of furniture, ceiling, lamps, decorative wall painting with flowers for the Yusupov Palace on the Moika, 1860s. Found in the Collection of State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg

Getty ImagesBehind the laconic facade lies the luxury and splendor of its interiors. Different palace halls were designed in completely different styles: for example, the Moorish Drawing Room is decorated in the Oriental style in memory of the family's ancestors. The palace halls are also packed with treasures collected by various rich members of the Yusupov family.

Princess Zinaida Yusupova in the Family Living Room

Getty ImagesThe last Yusupov, Prince Felix, found it unbearable to be surrounded by this barbaric splendor, so he preferred to live in an apartment set up especially for him on the palace's ground and semi-basement floors. The owner called his living quarters a bachelor's apartment.

'Portrait of Prince Felix Felixovich Yusupov, Count Sumarokov-Elston' by Valentin Serov

Russian MuseumFelix was an unusual person. Since childhood he had loved to dress up in women's clothes, wear jewelry and makeup – this was largely his mother's influence since she had been desperate for a daughter. All the noble families of the Russian Empire liked to gossip about the peculiar young man. It was rumored that he was homosexual, but there is no evidence to support this theory. Furthermore, Felix, like many Yusupovs, was very close to the imperial family.

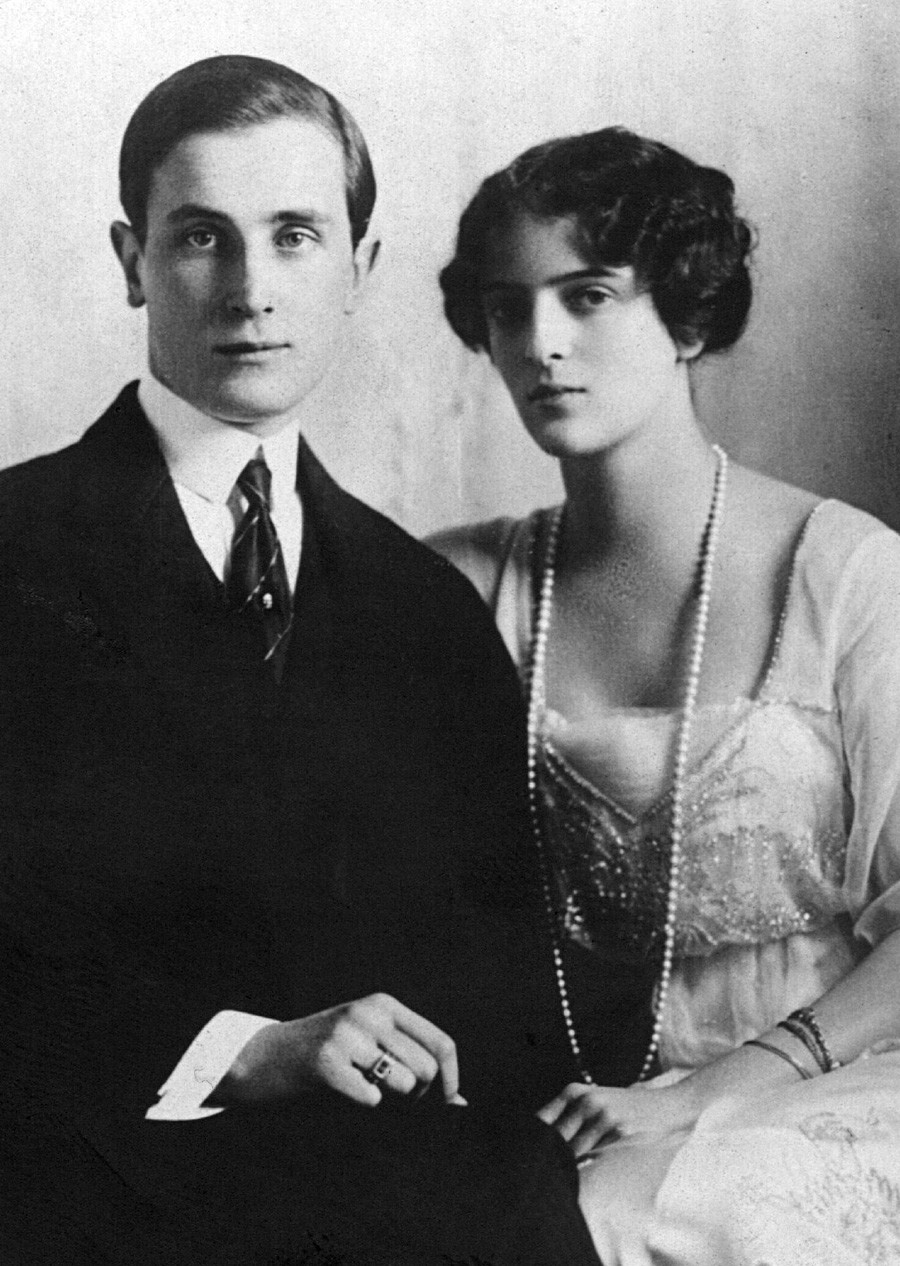

On December 17, 1916, Felix and his friend Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, who was a relative of the tsar, lured Rasputin to the Yusupov Palace. Rasputin was a peasant from Siberia, but also a close friend of the last Russian emperor, Nicholas II, and especially of the empress (there were even rumors of a love affair).

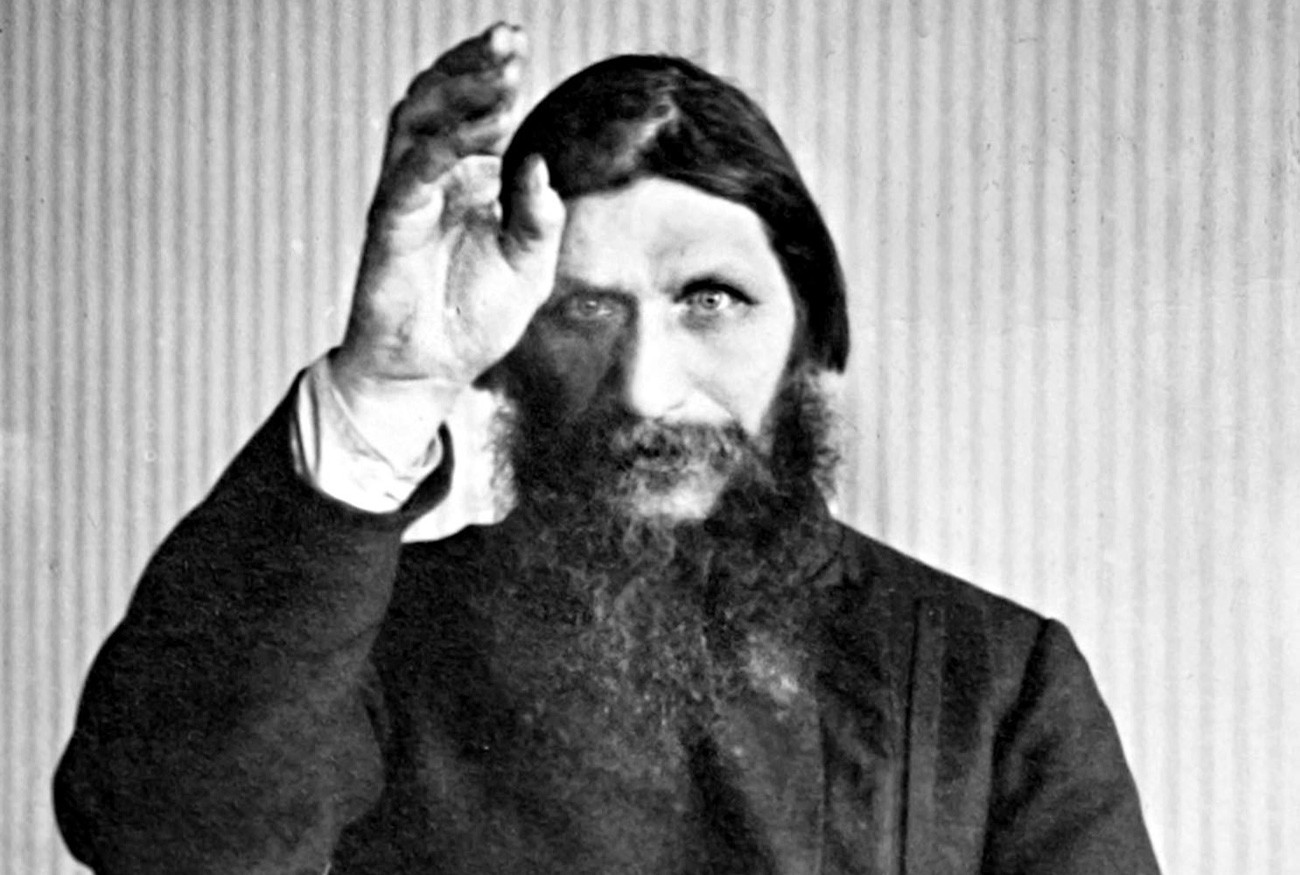

Grigory Rasputin

Legion MediaAt the same time, Rasputin had the reputation of being “a holy elder” and a healer - he had been able to stop the bleedings that afflicted the tsar's son, Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia. The tsar's inner circle, however, believed that Rasputin exerted too much influence on Nicholas, and on the empire's policies in general. They desperately wanted to rid the Motherland of "that rogue".

Felix Prince Yusupov and his wife Princess Irina of Russia, 1915

Public domainOn that fateful day in Yusupov's "bachelor apartment", the host and the Grand Duke treated Rasputin to tainted Madera and cakes laced with potassium cyanide. However, the poison did not work. There have been different theories as to why this happened. According to one, the sugar in the cakes and the wine neutralized the effect of the poison, thus protecting Rasputin from sudden death.

Wax figures of Felix Yusupov and Grigory Rasputin in the basement, a part of historical semidocumentary exposition "The Assassination of Grigory Rasputin."

Sergey Kompanichenko/SputnikAfter the failed poisoning, Yusupov shot Rasputin in the heart with a Browning pistol. However, the shot did not kill the Siberian peasant, and in agony Rasputin tried to strangle his would-be killer. The conspirators had to shoot him several more times, after which his body was tied up in chains and thrown into the Neva River. A later investigation established that the mortally wounded Rasputin remained alive for seven more minutes after he was dropped into the river.

Wax recreation of Rasputin's last night

Danita Delimont/Global Look PressThe palace basement were Rasputin was murdered now houses an exposition recreating the grim atmosphere of the last night of his life, with wax figures of its main protagonists. Tour guides say that at night museum guards hear steps in the basement that fill their hearts with terror. Some are convinced that the steps belong to none other than Rasputin, who allegedly possessed magical powers.

The Yusupovs saw the palace confiscated in November 191 when the Bolshevik Revolution forced the princes to flee St. Petersburg for Crimea, leaving many of their treasures behind. Some were hidden by the Yusupovs, and hidden so well that they've never been found. For example, one missing jewel was La Peregrina, a unique pearl worth over a million dollars.

Blue bedroom

Danita Delimont/Global Look PressAfter the Revolution, the Yusupov Palace managed to avoid the devastation that befell many other similar buildings. In 1925, it was turned into a Palace of Culture for Leningrad teachers. During the Second World War, it housed a hospital, and in the post-war years the building was given the status of 'historical monument of national significance'.

Currently, the Yusupov Palace houses a museum devoted to the aristocratic lifestyle of the Yusupov family, and it also serves as a venue for international conferences and diplomatic meetings.

Main staircase in Yusupov palace

Legion MediaAlyona Permyakova, a historian and a tour guide at the palace, says that tourists are particularly struck by the furnishings. The place has the genuine atmosphere of an aristocratic home. “Many of the exhibits not only belonged to the Yusupov princes, but are also placed exactly as they were before the Revolution and their owners' emigration. It is this impression of a 'lived-in space' that most visitors are struck by,” Permyakova says.

Tapestry Room

Legion MediaIn addition to the colorful Moorish Drawing Room, visitors are particularly impressed by the carved Oak Dining Room, the White Column Hall with its excellent acoustics, and the Home Theater, which they can see not only with a tour but also as spectators because the theater holds regular evening performances.

The house theatre of the Yusupov Palace

Legion MediaThe Yusupov Palace is open daily, both to groups and individual visitors with an audio guide. For more information, please go to yusupov-palace.ru

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox