Little by little, as the curves of the Sayan Mountains in southern Siberia pass by, the forest cover gives way to naked hills. After a 14-hour road trip from Krasnoyarsk, my bus finally arrives at Kyzyl, the capital of Tuva.

This republic, sitting at the gates of Mongolia, is one of the most remote corners of Russia. In addition to not being connected to the national railway network, there has been no direct air connection with Moscow until 2015.

In all honesty, Tuva enjoys a dismal reputation. It closes, by far, the overall ranking of Russian regions for its socio-economic situation, with the worst rates of crime, poverty, life quality and expectancy and one of the worst in terms of unemployment and alcoholism. The birth rates, interestingly, are the highest in Russia, though.

Motivated by years of desire to discover this mysterious land, renowned for its breathtaking landscapes and distinct culture, it is therefore with some trepidation that I set out to explore its heartland, home to some 120,000 souls.

Here, the faces have Asian features, while mine arouses curiosity. In fact, if, in 1959, the ethnic Russians represented 40% of the population of Tuva, in 2010, they were only 16%, due to their migration to other regions and the high birth rate of Tuvan people.

Many ethnic Russians testify about the difficulty of living in this region, which seems destined to remain on the margins of the world. Many natives here have little or no command of Russian, especially among the youngest, and learning Russian is often done in Tuvan, like а foreign language.

Tuva has a troubled history. Formerly dominated by Mongolian nomads, placed under Chinese imperial aegis from 1758 to 1912, and later integrated into the Russian Empire, it also experienced independence, under the name of Tannu Tuva (1921-1944), before becoming part of the USSR and then, the Russian Federation.

This turbulent past is explained by the location of this territory. Kyzyl appears to be the geographical center of the Asian continent, a characteristic celebrated by an elegant obelisk on the banks of the mighty Yenisei River, whose source is not far away.

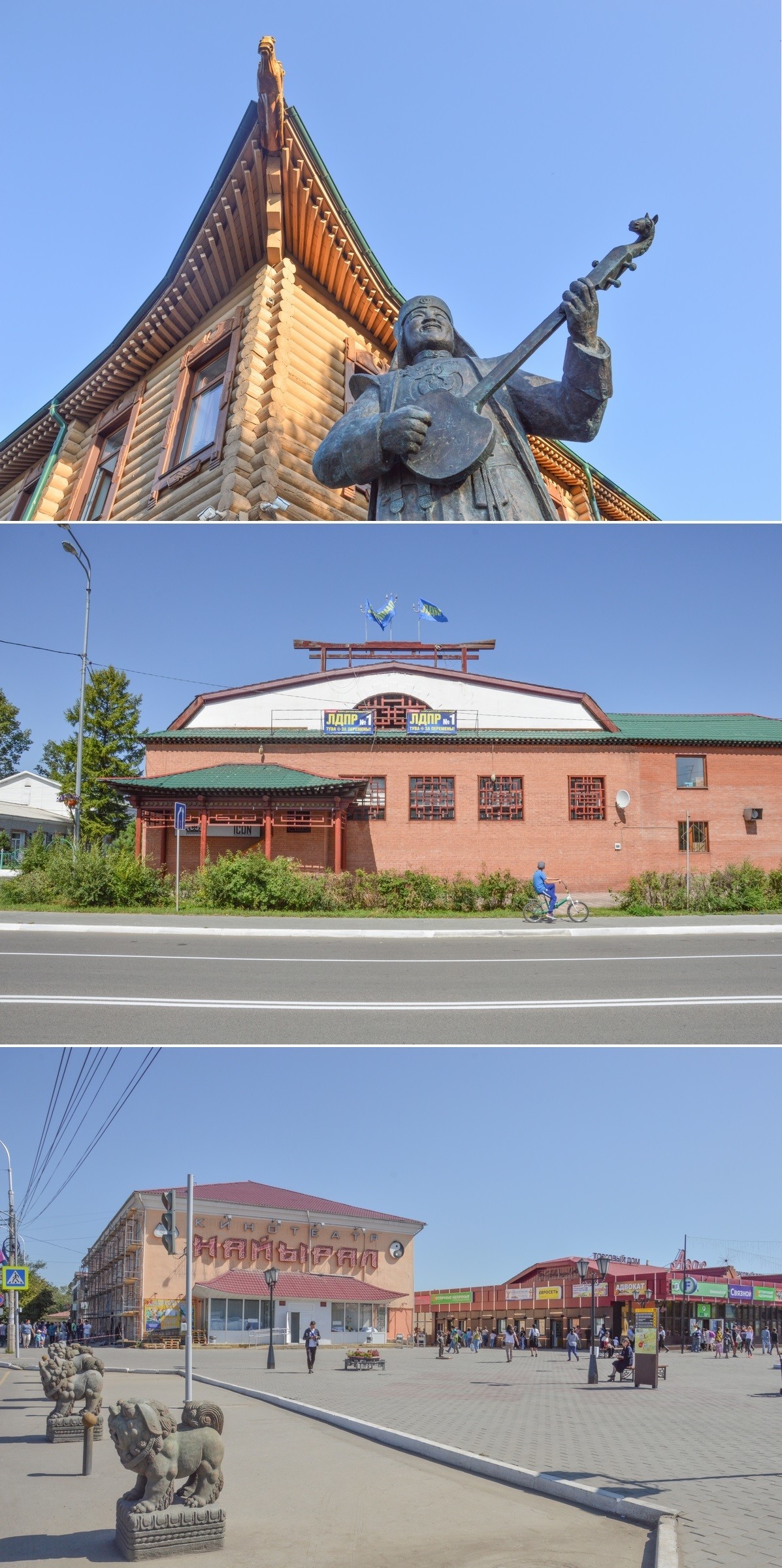

Throughout the streets, Asian symbolism is omnipresent. The shou, a graphic representation of longevity, adorns fences, benches and balconies in the shade of curved roofs, while the Buddhist influence, the dominant religion here, is palpable.

The locals are proud of their culture, and the National Museum of Tuva is the proof. Ancestral relics and more contemporary works of art, still inspired by the spirit of the nomads, the freedom of the steppe and the wisdom of the deities, are on display here.

There are also jealously guarded priceless treasures: Scythian artifacts discovered in the ‘Valley of the Tsars’, a major archaeological site in Tuva. These gold jewels dating from nearly 3,000 years ago are of such refinement that their creation techniques are still not understood.

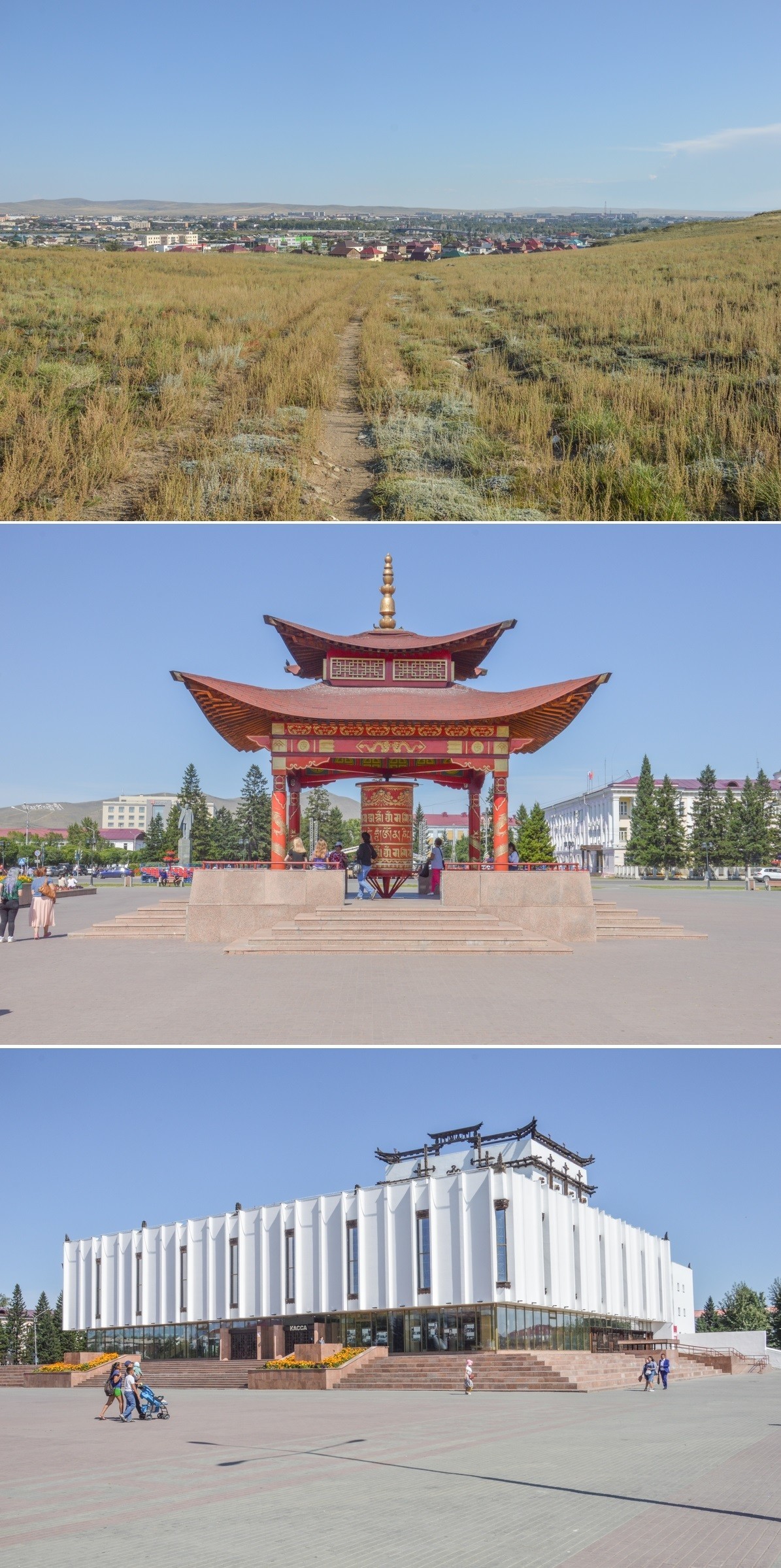

Tuva is also home to stunning landscapes, marked by a pronounced relief and steppe immensity. Only 10 minutes away from the center of Kyzyl, hikers can admire an ocean of hills and mountains that seem to melt under the merciless sun.

After suffering from a suffocating heat in the middle of summer, the climb up the sacred mount Dogee offers me an unforgettable spectacle: Kyzyl below, expanding like an oasis, while on the side of another mountain appears the largest Buddhist mantra in the world.

As elsewhere in Siberia, Buddhism here is strongly influenced by Shamanism. On the top of Dogee, a mast is hung with hundreds of prayer flags, while the paths wind between the ovaas, small stone pyramids, honoring the earth spirits.

A nine-meter high statue of Buddha sitting on top of the 12-meter high postamen watching over the Tuvan capital has been erected on one of the Dogee peaks in September, 2021. It is lulled by the buzz of strange and noisy flying insects.

Not a single tree, no shadow; the surroundings of Kyzyl are raw and bare. A simplistic look, but which is not at all devoid of poetry, the eye wandering between the horizon and the rounded lines of this expanse that the nomads have crossed a thousand times.

Thirsty, but filled with serenity, I finally return to the city, where my departure looms. I pass by the central square for the last time. A statue of Lenin, a Soviet relic, stands on the side, while a majestic Buddhist prayer wheel and a monumental theater, seeming to come straight from Tibet, are in the very center of it.

As I am about to get on the bus, I notice a bird of prey perched on the roof facing me. Is it one of those that accompanied me throughout my discovery of Kyzyl, hovering near my hotel balcony or above the peaks during my walk in the mountains?

It is, thus, under the benevolent eye of this sacred guardian that I leave Tuva, of which I had been advised to be wary, but by which I turned out to be delighted with. Finally, bathed by bewitching night lights like Roerich's paintings, its mountains bid me farewell.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox