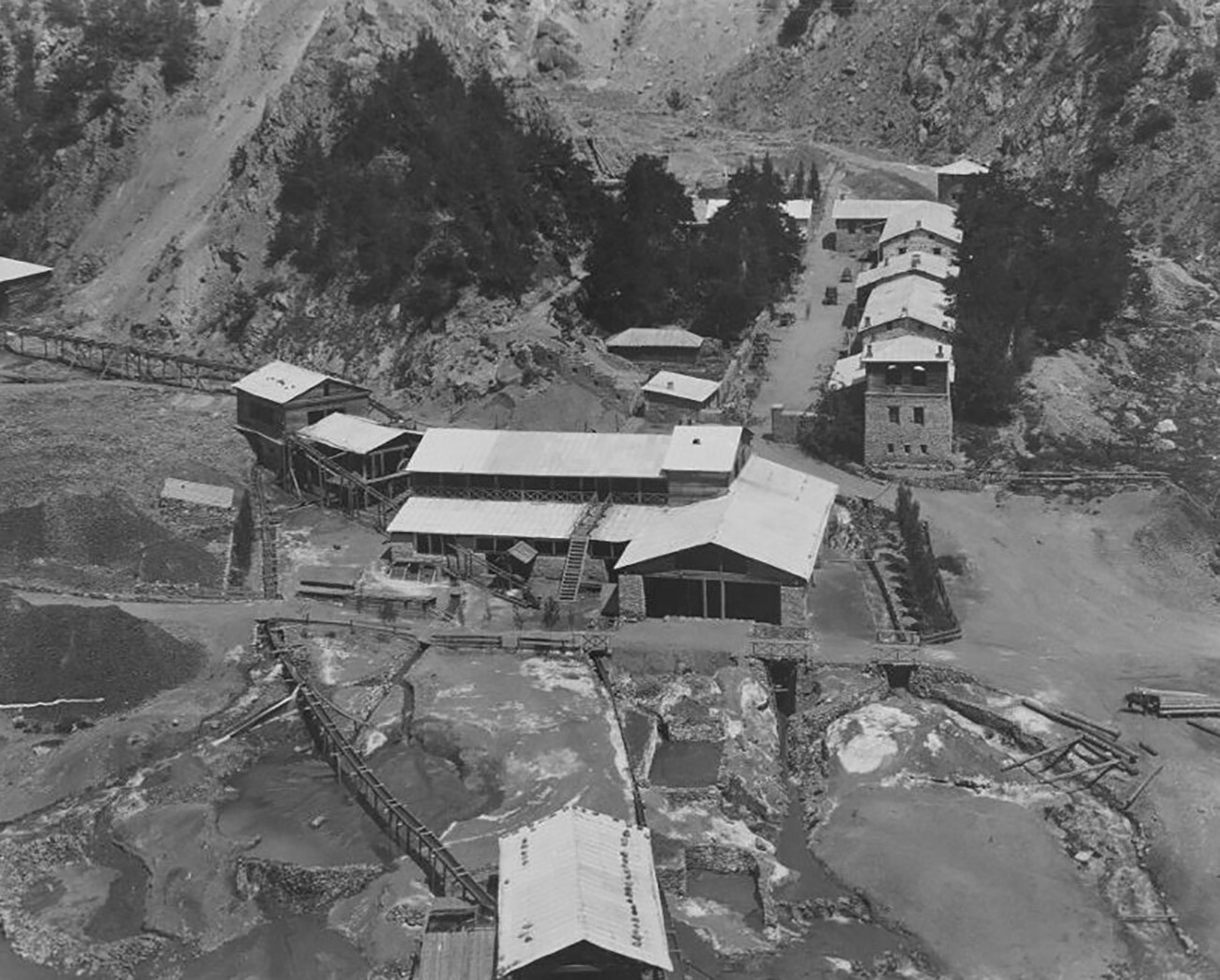

Sadon in 1890s.

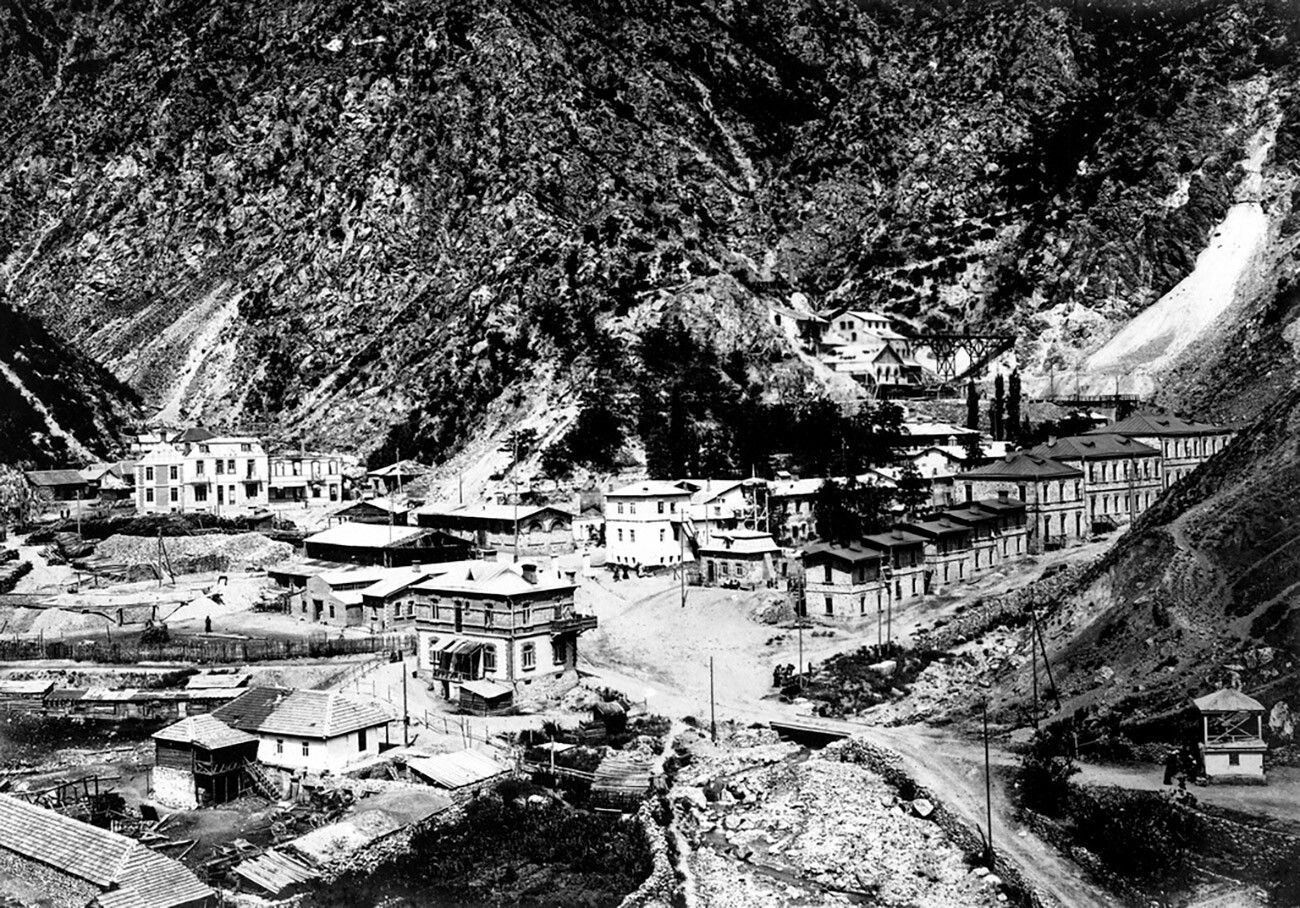

Ivan LipovoyEuropean architecture with small, quaint buildings and neat little streets - it’s an atypical sight for a creepy mountain gorge in the middle of the Caucasus mountains, to say the least. Small and tough village houses are a more common occurrence. The village of Sedon, North Ossetia, was built by Belgians in the 19th century, but, today, it is void of all life.

The Sadon lead mine gallery entrance, in 1910.

Public domainBack in the 1760s, major deposits of lead, zinc and silver were discovered in the Alagir gorge. Non-ferrous metals were needed for building up the military industry, as well as for medicine. The Sadon mine was the first in the Russian Empire and remained the largest until the 1980s.

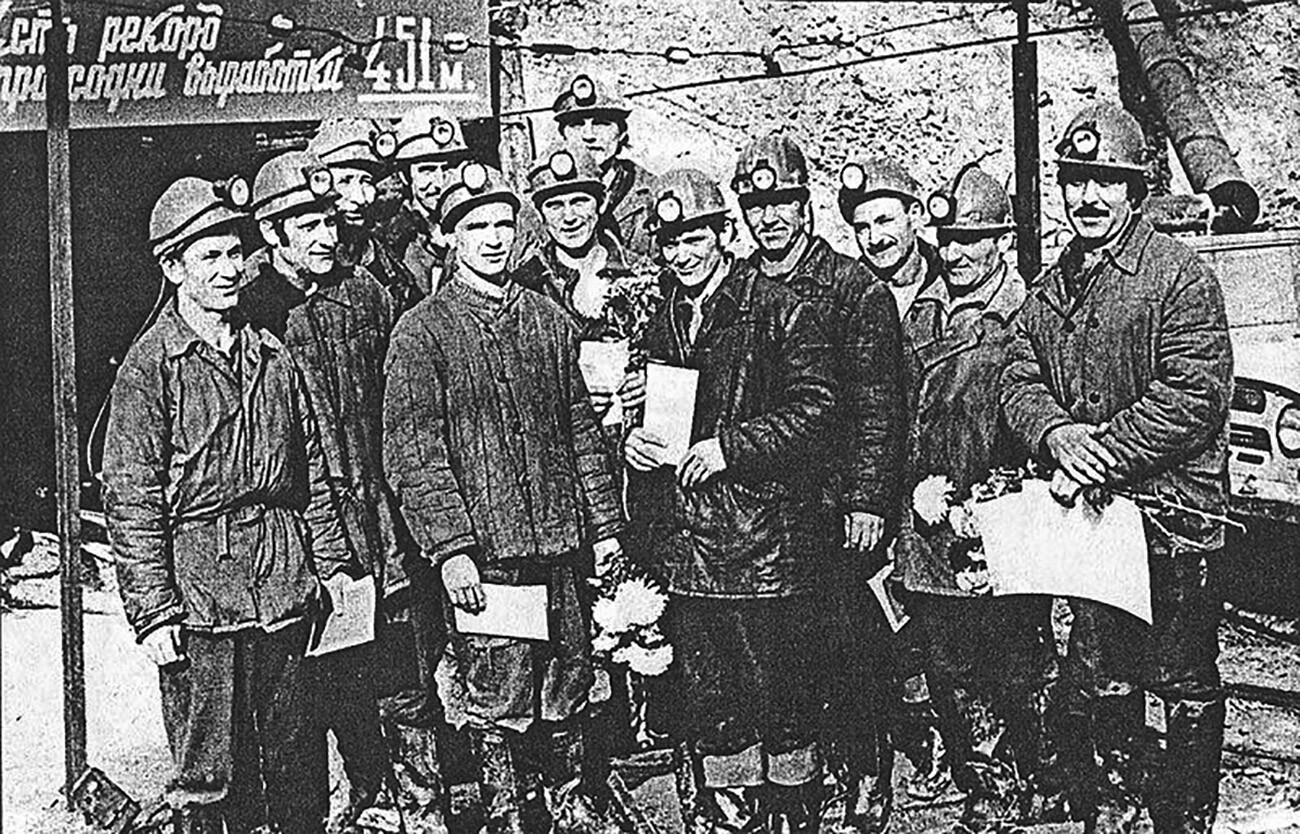

Workers of the Sadon mine, 1979.

North Ossetia republic newspaperGlobal development of the mine began in earnest only in the mid-19th century, when the Military Ossetian Road and access points to the site were laid. The Sadon mine is situated in the mountains and, in order to set up the enterprise itself in such inhospitable conditions, the Russian Empire commissioned the best foreign specialists.

“Many of the mines were built by Greeks, as they’re excellent masons,” says local guide Ruslan Bimbasov. “The plots were subsequently rented out to a Belgian mining and chemical society.”

In 1886, the Belgians began constructing accommodation and infrastructure for miners and their families: a school, a hospital and roads appeared. Besides developing the mine, the Belgian Alagir Society was developing a lead slag processing plant in the neighboring Mizur settlement.

After the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the enterprise was nationalized. The Belgians left, while the Sadon lead-zinc plant began developing at a colossal rate. Securing a job there was considered a huge deal. In the early 20th century, Sadon numbered 300 people - in 1939, the population grew to more than 4,000.

According to Ruslan, different sources claim that, during the Great Patriotic War, every second or third bullet fired was forged from lead mined at Sadon. It’s difficult to ascertain this today, of course. However, mining there was colossal in scale. In the early 20th century, the amount mined stood at 25,000 tons a year, but, by 1970, it was peaking at 745,000.

After the war, Soviet geologists began developing new lead and zinc mines across the country. The Sadon mine used antiquated technologies, which resulted in numerous losses. Furthermore, the land was just about drained of its useful minerals. By the mid-1980s, mining was practically stopped, while, after the breakup of the USSR, the factory barely made ends meet. However, more trouble soon came.

In 2002, the Sadon lead and zinc plant and the village itself were destroyed by a mudflow, caused by the Sadonka mountain river. It looks pretty unassuming at first glance, however, during the event, the water level increased by seven meters. After the catastrophe, the first floors of many homes were buried under mud and made unlivable. There was no opportunity to rebuild. The 500 people living there were relocated to the Alagir and Mizur settlements several kilometers from Sadon.

Although Sadon officially still has a population of 87, in truth, no one lives there anymore, Ruslan points out. Former residents continue to visit, in order to check on their old homes. The Sadon plant was officially closed in 2009, due to natural resource depletion. As for the village, it ceased to exist in 2013, with the administration relocating to Mizur.

There’s not a single trace of all that extravagant architecture anymore. Everything is gradually falling apart. Hungry stray cats roam what remains of the village’s streets - they’re often fed by people from neighboring settlements and tourists who come to see the ruins.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox