‘Sorrowful Room’.

Museum of World Funeral CultureThe fact that our time in this world is not eternal is not something we want to be reminded of too often. And the idea of making items of mourning into museum exhibits seems completely shocking. All the more surprising that you can find Russia’s only Museum of World Funeral Culture, located on the outskirts of Novosibirsk, in any guidebook to this Siberian city.

Here's the entrance to the museum.

Museum of World Funeral CultureThe Museum of Death is located next to a crematorium about an hour's drive from the center. The first thing you notice is that both buildings are bright orange and can be seen from afar. This cheerful color was chosen by the founder of both institutions, Novosibirsk entrepreneur Sergey Yakushin.

His interest in the ritual sphere emerged out of personal circumstances - in the 1990s, he was diagnosed with cancer and, to overcome his fears, he began collecting various items related to the culture of mourning and burial in different nations. He organized an international funeral exhibition in 1992, opened the city’s first crematorium in 2003 and the Museum of Death in 2012.

...and the crematorium.

Kirill Kukhmar/TASS“I didn’t believe at first that the museum would be of interest to anyone,” says Tatyana Yakushina, today’s museum director and wife of Sergey’s son. “When we opened, I sat here alone and if three people came to see us in a day, it was a big success.”

Today, it is one of the most popular museums in the city. “Of course, the topic of death is a taboo, no one wants to think about scary things, but, in fact, it is the only guaranteed event in everyone’s life. Everything else may not happen,” says Tatiana. “People can come to us with their fears, questions, stories and talk.”

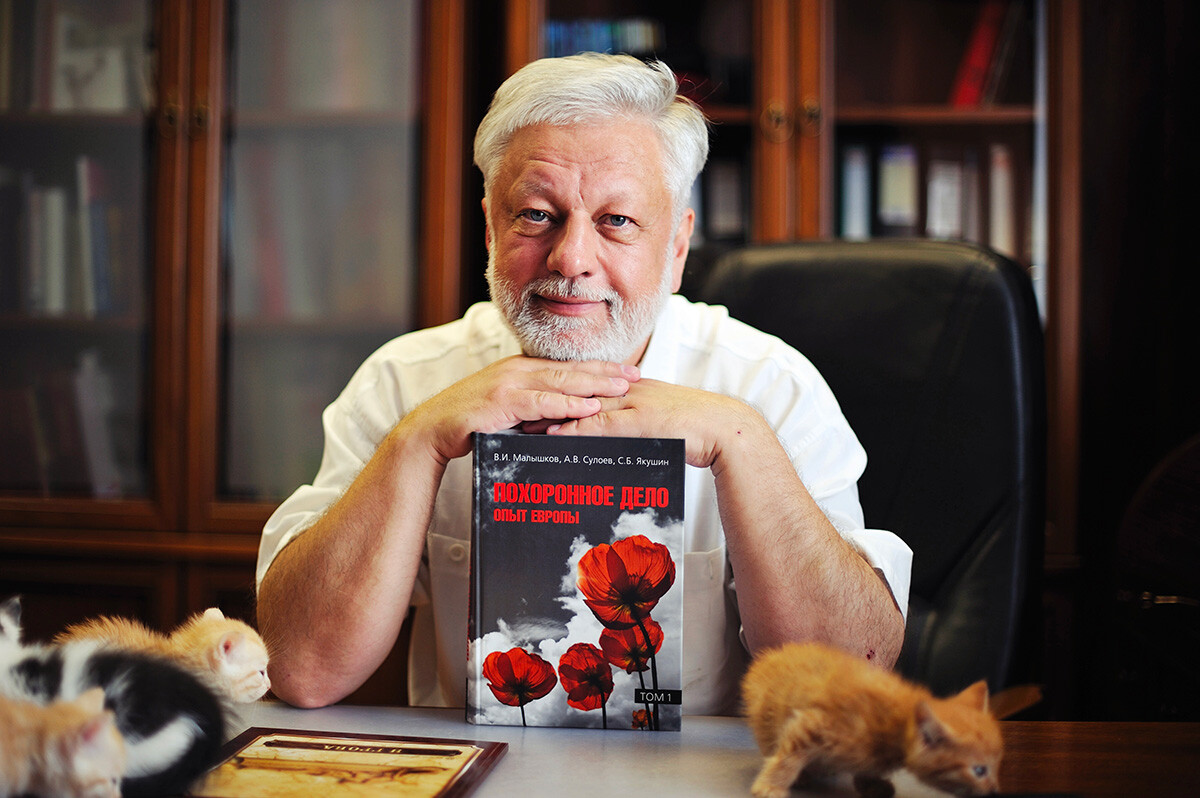

The founder of the museum Sergey Yakushin.

Museum of World Funeral CultureBack in 2013, Sergey Yakushin drew up a plan for his funeral at his own crematorium. “Everything was specified beforehand, from the route of the procession and the type of coffin made in his workshop to certain songs which played at the funeral. And one of his wishes was that the cortege would walk through the main streets of Novosibirsk, his hometown and favorite city,” Tatiana says.

Yakushin died in 2022, but he left a large legacy - about 30 thousand exhibits related to burial traditions. They are located in three separate pavilions, which can take literally hours for visitors to examine.

“We introduce people to the history of burial culture, so they can see the experiences of the past,” says art director and tour guide Inna Isaeva as we walk to the ‘Sorrowful Room’ exhibit, where a mannequin in the form of a grieving woman from the late 19th century sits. “We don't scare anyone with death, our museum is about life.”

The first and largest room is devoted to the culture of remembrance in Victorian England, when secular society had a protocol governing behavior after a funeral and the timing of mourning. “Back then, funerals were believed to be the last celebration in a person’s life and rich people did not skimp on organizing the event,” she says. Shown here are antique engravings, numerous mourning gowns, costume jewelry and lockets with locks of hair of the deceased, as well as different kinds of funeral urns.

The second room tells about funerals in different cultures and religions: Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Catholicism, Orthodoxy. And, of course, the Soviet funeral. A replica of an embalmed Lenin, just like in the Mausoleum, Soviet coffins, upholstered with velvet, symbolizing the “fire” of the revolution, because the Soviet man had to not only live, but also die in a new way, explains Inna.

The replica of embalmed Vladimir Lenin.

Museum of World Funeral CultureThe third hall has an exhibition devoted to the 10th anniversary of the museum, from the first exhibits to thematic displays about the Chernobyl accident.

As you go through everything, little by little you get used to the skeletons (thankfully, they are not real), sarcophaguses, mourning robes and even creepy photographs.

This exhibition shows the funeral traditions of Old Rus.

Museum of World Funeral CultureIn addition to Yakushin's collection, there are exhibits (mostly documents) donated by other people and other museums. For example, there is a replica of a reusable coffin with a reclining bottom from the Funeral Museum in Vienna [Bestattungsmuseum].

“People often ask us, ‘Aren't you scared?’ We’re not scared,” laughs tour guide Evgeniya Yudina. “It’s scary if you’re standing at a bus stop late at night somewhere in the megalopolis. But our museum is about culture, about science.”

Yevgeniya is a philologist and used to teach at school. “My family was among the first Novosibirsk residents to resort to cremation back in 2003,” she says. “And it so happened that I was a customer of this crematorium more than once. Later, I met Tatiana, we became friends and she offered me a job at the museum.”

She has been guiding tours here for two years now and she believes it’s her destiny.

Hair decorations.

Museum of World Funeral CultureInna, on the other hand, came to the Museum of Death from the drama theater. She had never been to the museum before, she had only seen the museum's founder at his funeral, but she was fascinated by the artistic taste of his collection.

“I treat this subject from a researcher's point of view,” she says. “I don’t have nightmares, there is a great distance between this subject and myself, I understand that it will happen to everyone, sooner or later, and this distance helps me first of all to keep myself safe and secondly to see a lot of new things, but not to dive headlong into it.”

As the staff explained, we need to understand that death is a part of our life and we need to treat it with respect. But we should not flirt with it.

“I won’t say that I don’t think about death at all, sometimes I do,” Inna says. “But, I try to focus on my life, what is in my power and purpose. Working here, you see the fragility of life. We will all be gone, the only question is what we will leave behind and how we will be remembered.”

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox