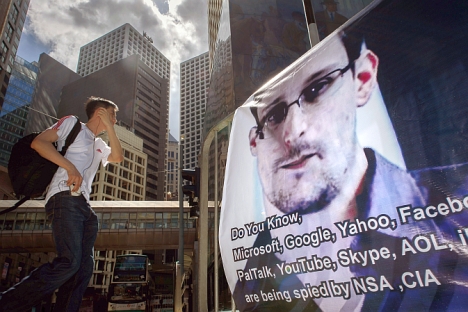

The Snowden affair has provided a fitting end to the 2012-2013 global political season – a combination of pathos and cynicism, farce and drama, with hopeless ambiguity as its main symbol. Source: AFP / East News

A different kind of confrontation is brewing in the world. In the past, Edward Snowden would have brought his revelations to Moscow and offered his services to the Soviet intelligence service. There were many like him who grew disenchanted with the West and were drawn to the promise of communism. Of course, there were also Soviet intelligence officers who chose freedom in the West.

However, today the main enemy of a major intelligence agency – a closed institution by definition – is not other intelligence agencies but open society.

US army private Bradley Manning and National Security Agency contractor Snowden offered up information they considered important not to an enemy state but to the general public, turning the old order upside down. Sharing secret information with an ideological or strategic enemy is considered treason in any country, whatever the motivation. But to many, exposing government agencies’ interference in the private lives of citizens and violations of constitutionally protected freedoms is an act of patriotism.

Snowden’s supporters in the United States include leftwing and ultra-liberal politicians as well as ultra-conservatives and libertarians such as Sen. Rand Paul, who believe the government should stay out of people’s lives.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s reaction added an interesting twist to the story. He said that Russia would not extradite Snowden to the United States, which was to be expected, but his words did not betray any sympathy for the fugitive American. As a former intelligence officer himself, Putin could hardly be expected to feel sympathy for someone who violates his oath and reveals state secrets.

A new kind of confrontation is taking shape in a world where nothing is secret any more.

On one side are the intelligence agencies of the world, which believe it is their duty to know as much as possible about people and to keep them in the dark about their own activities – in the name of universal security.

Standing on the other side are those who believe that people have the right to use any means available to lift the veil of secrecy from intelligence agencies and to keep them out of their personal lives.

This had been a relatively minor confrontation, but the modern global information community has acted as a huge magnifying glass and a powerful catalyst.

Whistleblowers, however, are of little interest to rival intelligence agencies. The facts that whistleblowers reveal to the world are usually well known by the agencies. Moreover, an agent’s value lies in being part of the system for a long time, even as a small cog. Those who go public and sever their ties with an institution are not worth a dime.

Manning, who passed sensitive US government materials to WikiLeaks three years ago, and Snowden, who went public with information about the Internet scouring program code-named Prism, might just be underachievers in search of notoriety. But really, it doesn’t matter why they did it. The upshot is that society is trying to protect itself from the growing technical capabilities of intelligence agencies. Snowden has simply confirmed what everyone already suspected – that intelligence agencies are using social media and other communication systems for their own purposes. But such weapons can cut both ways, and there will always be people willing to use these new technological capabilities against the agencies. There will likely be more such whistleblowers, and not only in America.

All in all, the Snowden affair has provided a fitting end to the 2012-2013 global political season – a combination of pathos and cynicism, farce and drama, with hopeless ambiguity as its main symbol. Opinions of Snowden vary greatly and will likely continue to divide people.

The trend toward disunity in the world is much stronger than the trend toward unity. The overwhelming feeling is one of exasperation. Nothing is going as expected and different social groups and countries cannot agree on anything. No one is satisfied with the outcome, although for different reasons, and no one knows what to do to make things right.

Fyodor Lukyanov is Editor-in-Chief of the Russia in Global Affairs journal.

First published in RIA Novosti.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox