Boris Eifman: I still feel a great urge to create something new

Boris Eifman, artistic director of the St. Petersburg State Academic Ballet Theater.

Sergei Konkov/TASSRBTH: You have been known for many years as a choreographer who creates new original ballets almost every year. Could you tell us how and when art became part of your life?

Boris Eifman: I was born into an ordinary educated middle-class family in a small town in Siberia and my family did not have a habit of taking young children to the theater.

I was a very active kid: I sang and danced and took part in amateur theatricals. I first saw Swan Lake when I was about eight years old.

RBTH: Were you impressed by it at the age of eight?

B.E.: I remember it as if it were yesterday: I’m standing in the upper circle, it’s the end of Act Three and the tutti in Tchaikovsky’s music is so huge, so dramatic, when Siegfried’s betrayal is revealed. I was so affected by it emotionally that I burst into tears. I think the stress I went through then became the basis of my life-long addiction to theater.

RBTH: Was it then that you decided to go into ballet?

B.E.: Many people dance; in the USSR, all those extracurricular activities were a tradition, so it was hard to avoid that path.

What surprises me is another thing: Already studying at the ballet school, I began to create some improvisations, works of my own. At 13, I started a journal where I described my first productions and creative ideas. There’s another notebook that is called “My first productions.” It also dates back to when I was 13.

RBTH: And then you met Yakobson…

B.E.: Yes, at 15, I met Leonid Yakobson, a choreographer with a tragic fate. At the time, he was on the banned list and could not work either in Moscow or Leningrad.

I began asking him how to become a choreographer. He was very surprised that the question came from a boy of 15. And he told me: “One cannot become a choreographer, you have to be born one.”

As a person prone to doubt, later I kept testing myself, wondering whether I I’d been born a choreographer or not. And all my childhood and early youth I was working to become one.

RBTH: You started working while you were still studying: First you received an invitation to produce a ballet for TV, Rococo Variations, and then you were invited by the Vaganova Ballet Academy and the Maly Theater in Leningrad. How did that happen?

B.E.: As you understand, I had no connections. In general, I found it hard in Leningrad because it’s a city that is not very welcoming to outsiders. It took me many years, more than a decade, before I was accepted. I think I received those offers because I was working very hard.

I did choreography everywhere I could: on TV, on the stage… As a result, Igor Belsky, who was not among my teachers but who at the time was the chief choreographer at the Maly Opera and Ballet Theater, invited me to make a production of Gayane. It was out of the ordinary because we hardly knew each other and he had Genrikh Mayorov and Valentin Yelizaryev among his pupils, and yet he chose me.

RBTH: Would you say that back then young choreographers enjoyed more attention and trust than now?

B.E.: I think there’s not much truth in complaints that these days it’s hard for young choreographers to advance. I think things were much harder for us: Nobody worked with us especially.

As a student, I’d get up at 8 in the morning and go to the ballet studio to work on my choreography because the studio was occupied from 10 in the morning till late in the evening.

I very much wanted to observe Yakobson in rehearsals. Yet, he – who often invited me over for dinner and vodka – didn’t allow me to watch his rehearsals. I can understand him: He felt constrained in other people’s presence. Yet I managed to sneak in and – through the window or a crack in the door – watch him at work.

RBTH: You now must have many such onlookers yourself…

B.E.: In the 40 years that I have been working in the theater not a single young choreographer has asked to attend our rehearsals. I fail to understand what drives young choreographers these days, what motivates them to choose this profession. It demands full commitment, an immersion into this world, sacrifice, constant learning and self-improvement. Readiness at any moment to respond to the calling and make the most of a chance you have been given. And chances are plenty.

Why am I so touchy on this subject? I want my Palace of Dance, which at last is taking shape, to be a place where young choreographers can develop. Secondly, I also want to see young choreographers working in my theater. So far, I can see only one candidate, Oleg Gabyshev, but he has a busy workload as a soloist and I have no-one to replace him.

RBTH: Many choreographers of your generation - Jiří Kylián, Mats Ek, William Forsythe – have said goodbye to ballet. Have you ever been tempted to do the same?

B.E.: I work seven hours in a ballet studio every day. Moreover, I’ve started on a new journey, which is probably quite crazy: I’m redoing my old ballets. Just recently we showed a premiere of Tchaikovsky. Once it was my most successful ballet, which was very well received in Paris and New York. It hadn’t been on stage for a number of years and I decided to revive it.

RBTH: But in effect you created a completely new production.

B.E.: When I looked at the original version, I realized that it was a 20th-century ballet. I am not interested in a museum exhibit, I need a production that would be up to today’s level of my theater, to my own level… I realized that I had to make a new production of Tchaikovsky.

And I created a ballet 95 percent of which is made up of new choreography, new dramatic accents, sets, light. In essence, it is a new ballet under an old name. Yes, Kylián and Forsythe are taking stock of their work, whereas I, on the contrary, feel a great urge to create something new. Furthermore, I’m discovering new opportunities for myself.

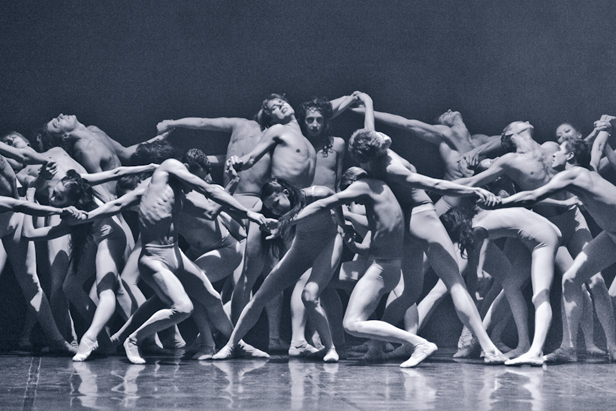

RBTH: One of your latest premieres is the ballet ‘Rodin.’ Why did you choose a French sculptor rather than Vera Mukhina or, say, Michelangelo?

B.E.: I could show you piles of notebooks, all in my handwriting. They contain everything that I know about Rodin, everything that has been written about him in different languages, and everything that I think about him. And the purpose of all that is to be able to come up with the movements. In order to create movements, I must be filled with information and ideas. I now probably know more about Camille Claudel’s love life than her relatives do.

Creating a ballet is an immersion. And it involves not just your consciousness but your subconsciousness, too. All this information is required to stir the choreographer’s consciousness and – which may be more important – his subconsciousness as well.

I think intuitive insights are very important in creating a ballet. That’s why before producing Rodin I spent six months in “desk preparation,” accumulating the relevant knowledge, preparing for this work. I had listened to all the French music of the 19th and early 20th century, an ocean of music: Ravel, Debussy, Massenet, Saint-Saëns, Satie. I know, these days, choreographers don’t work like this but for me, this is the most interesting part.

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox