Remember tucking yourself in to bed and then reading an illustrated story about sugar processing? Yeah, me neither. However, this was par for the course for children in the Soviet Union’s early days, when talented illustrators devised ingeniously engaging and eye-catching ways of coaxing kids into the workers’ struggle.

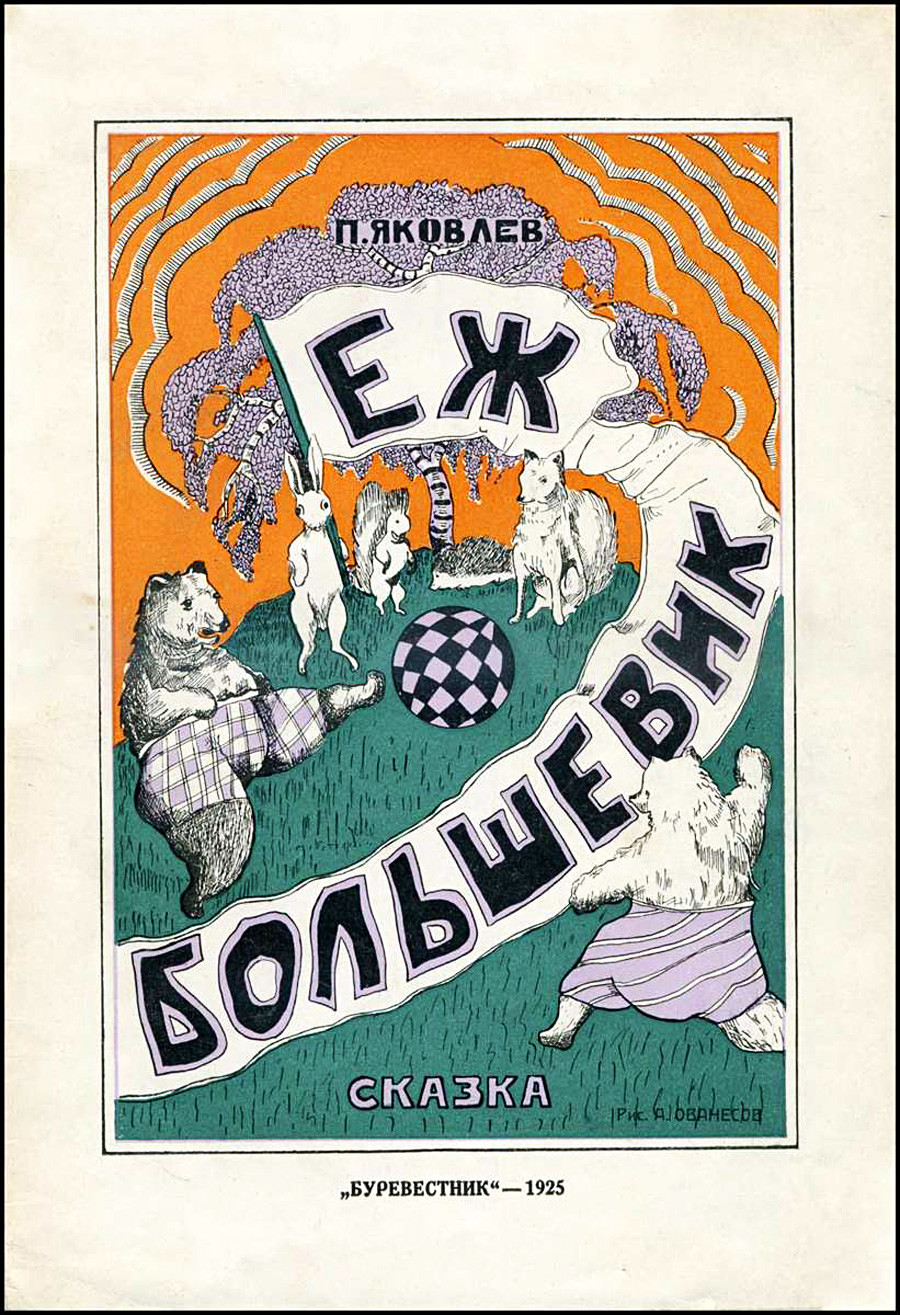

This illustrated poem charts the inner forest struggle between a “worker hedgehog” and a “brutish Tsar boar.” The tyrannical boar, who prevents the hedgehog’s inter-species comrades from playing football, meets his comeuppance when the animals (led by the noble hedgehog) march through the forest chanting “Eternal freedom to the feral people,” and then depose their oppressor. Sounds familiar…

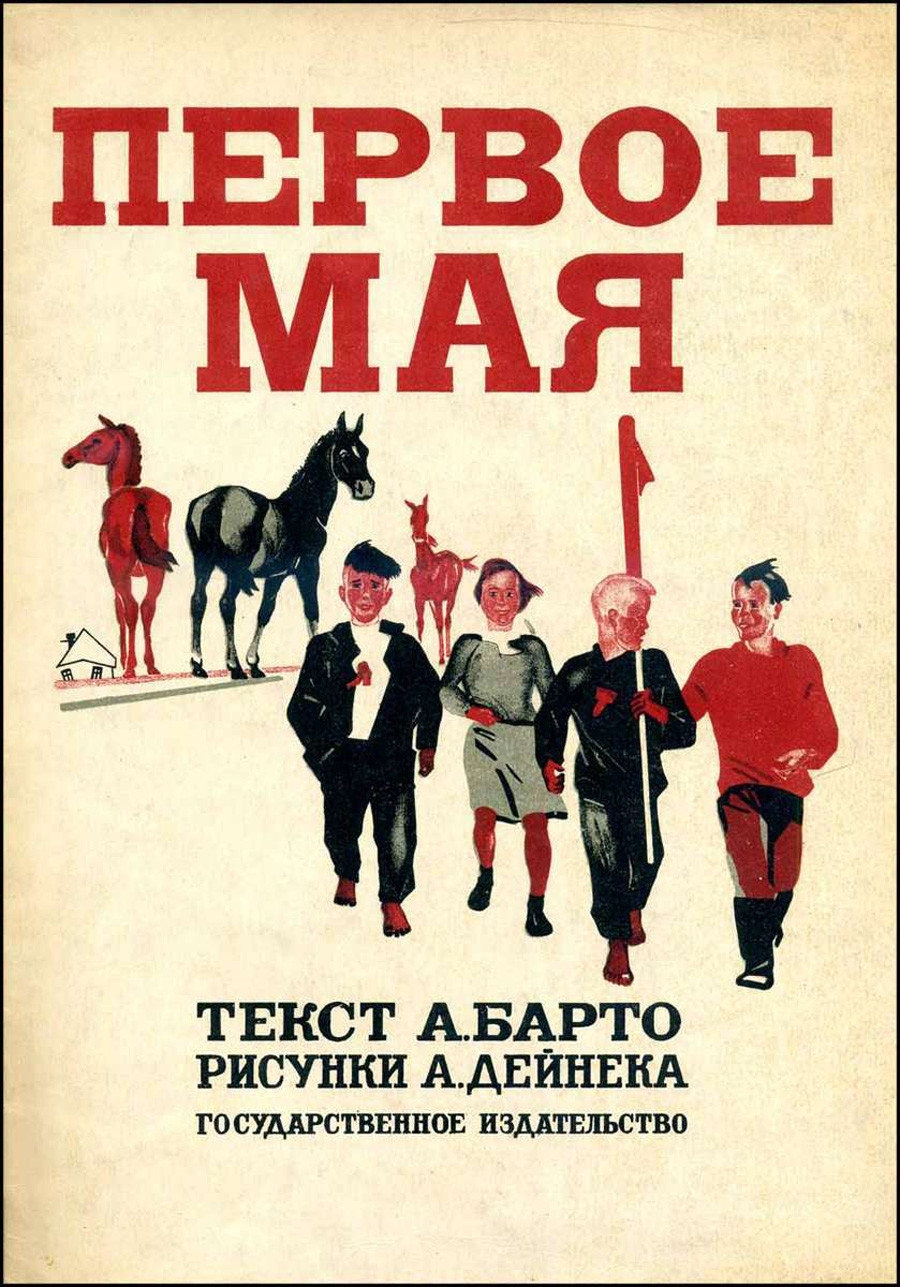

After waking up on a hot spring morning and eagerly plowing their collective farm, brothers Fedka and Aleshka get the chance to do what most kids can only dream of – head to the May Day labor parade on Red Square. Be it trains or airplanes, the boys repeatedly express their marvel at Soviet technological advancements, then hit the orphanage for a chat with the children from the All-Union Pioneer Organization and about Lenin’s life. Ah, childhood.

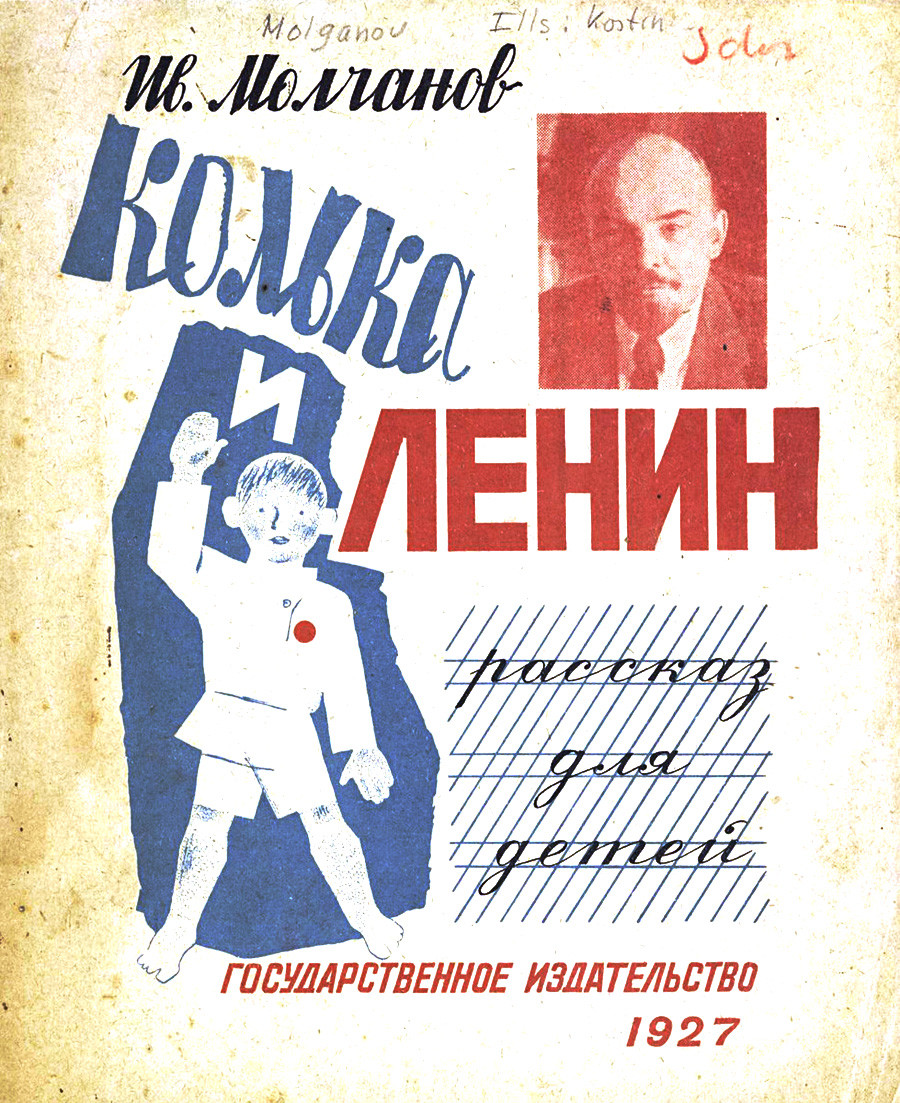

“What are cities?” ponders Kolka as he glares out his window at the trains gone by. He knows that cities have houses the size of factories and trams that can withstand any weather, but who is to thank for all this? “Lenin – the nice old man who led us to victory,” his book tells him. Who else could it be?

That night – as if by magic, Kolka meets the wise old man, who shows him the world (or more specifically, the impressive Soviet railway system). Then in a dark turn of events, Kolka realizes that it was all a dream when he wakes up and reads in the newspaper: “LENIN IS DEAD.” All that imaginary rail travel for nothing!

Not all heroes wear capes. Indeed, some can even be found in the local sanitary commission.

That’s how local legend Yasha is talked about in this book: his hygiene-related endeavors in the council and his tractor-driving skills have all the other boys wanting to be like him. But most importantly, he longs to muck in with the peasants (which Jews were apparently not allowed to do under the Tsarist regime), and to prove that Jews can in fact plow. Yasha’s efforts are not in vain, for his apples and cucumbers soon become the envy of all the farms in the vicinity. Happy days.

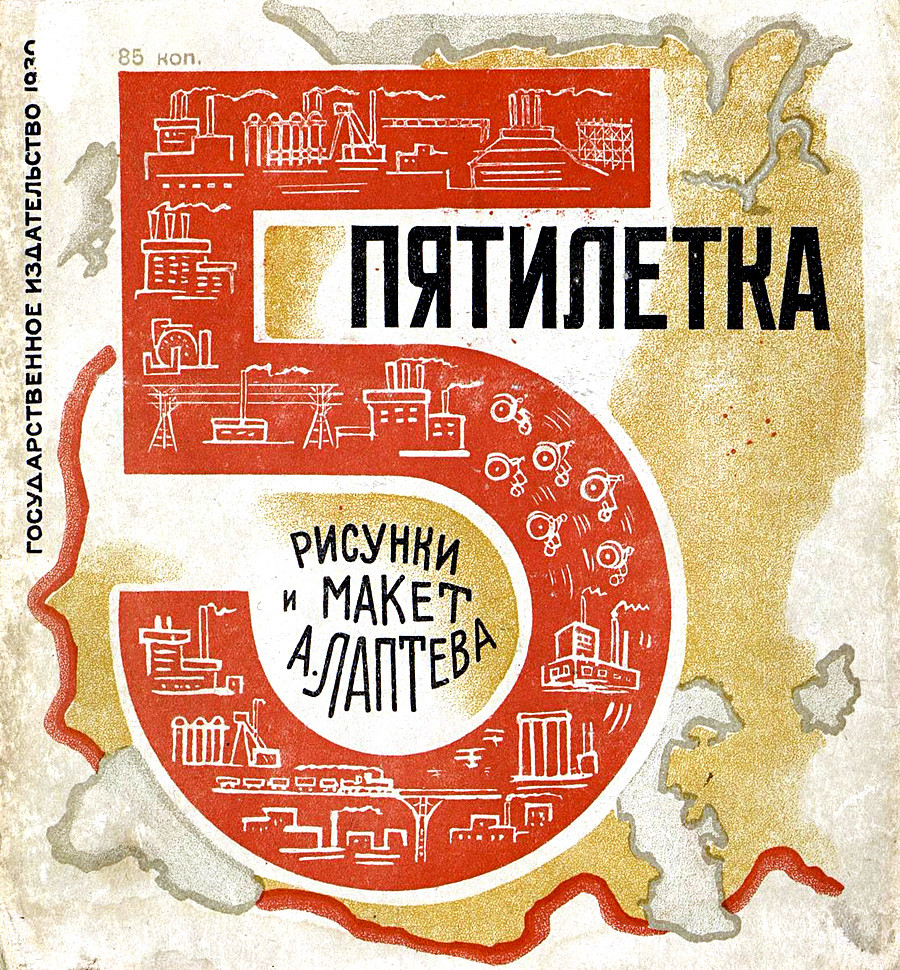

Stalin's first five-year plan doesn't immediately strike you as the kind of thing children lose sleep over, but the Soviet government made a real go of making the project as aesthetically interesting as possible. Using bright colors and engaging graphs, the book hammers home the glorification of new industries, making it all look as simple and exciting as arts and crafts hour.

For the Bolsheviks, it was important that children know about where their food came from. Why? Because the answer was, of course, the Soviet Union’s outstanding farming machinery. No fantasy fairytales here, literally just a step-by-step account of how beets are plowed, extracted from the ground, turned into juice and then into sugar. Enthralling stuff.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this illustration is less a lesson in the tenets of Bolshevism, and more a sermon on how great a guy Lenin is. I mean look at him – he buys one kid a boat, he’s doing food runs for a kindergarten, and he’s even redistributing the bourgeoisie’s caviar and cocoa to kids who deserve it. He’s basically Santa Claus, but with a better moustache.

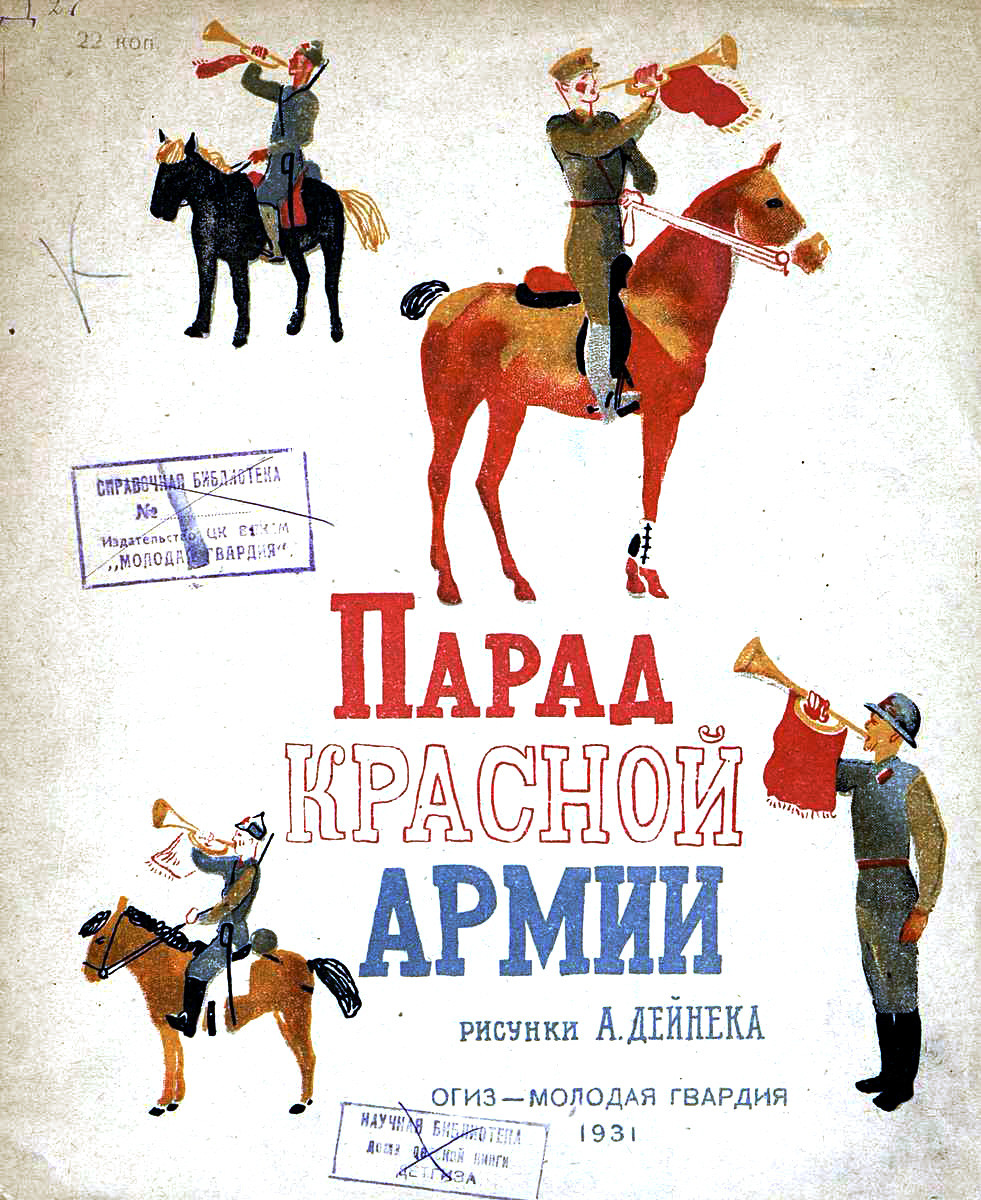

One of the more abstract Soviet children’s illustrations, The Red Army Parade, uses light red and yellow colors to make it look like the Revolution is in a constant state of Indian summer. The parade’s individuals are eternally blessed doves and beaming suns, while the crowd is portrayed as a warm, inclusive and unthreatening place. Certainly one of history’s most artful ways of encouraging kids to join the army.

Perhaps the two most common themes of early Soviet children’s literature are realism and reader involvement. Neither is more apparent than in The Subbotnik, which runs with the seemingly banal theme of locomotive work, but makes the reader an active participant in the construction of communism. By the end of the poem, the protagonist (depicted as a faceless child) is receiving direct orders from the boss, who needs an extra hand unloading potatoes: “Don’t look to the sides! Back up straight! Chest up! Merrier!”

For your hard work, you’re rewarded with making it home on time to a big plate of potatoes. Good job, comrade.

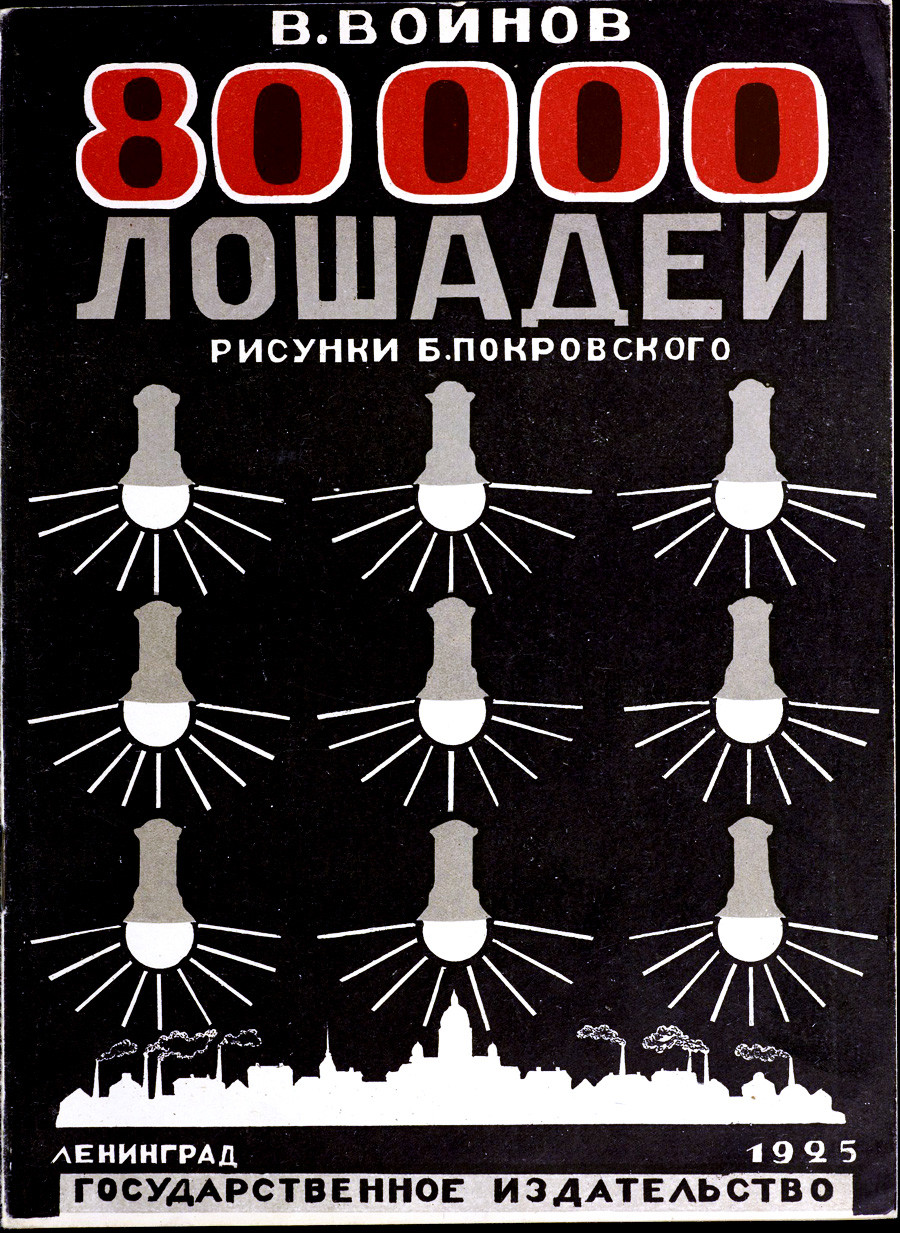

There was the Emerald City, and then Sleeping Beauty’s castle – but none can compete for children’s hearts quite like the Volkhov Hydroelectric Plant. Russia’s first water-powered energy planet, located on the Neva, was immortalized by this rhyming poem which, with the help of some historical revisionism, capitalizes on the plant’s grandeur to show how “Leningrad rose from the water.” The “80,000 horses” refers not to anything animal-related (you know, the kind of thing kids like), but rather to the turbine’s horsepower.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox