Princeton University uploads digital versions of Soviet children’s books

Princeton University.

Alamy/Legion MediaRussophiles and those with an interest in children’s books now have the opportunity to make use of a fascinating new literary resource thanks to Princeton University Library in the U.S., which has uploaded a new digital collection of Soviet children’s books for open use.

The first 47 imprints in the collection were digitized in preparation for a symposium at the university on illustrated literature for children from the Soviet era. Another 112 were added in June in preparation for a second symposium planned for spring 2017.

The physical collection of imprints is part of the Cotsen Children’s Library, a collection of illustrated literature for young readers, featuring materials from around the world from the 15th century to the present day.

“The collection and the endowment used to develop it were gifts of Lloyd Cotsen, a Princeton alumnus and children’s literature enthusiast and collector,” Thomas Keenan, Slavic East European and Eurasian Studies librarian at Princeton University, told RBTH. “It is the product of several decades of collecting, first by Lloyd Cotsen himself and subsequently by the Curator of the Cotsen Children’s Library Andrea Immel.”

The Russian holdings of the Cotsen Library for the first two decades of the Soviet era – the period from the October Revolution to the beginning of WWII (1918-1938) – number approximately 1,000 titles.In this period, when the Soviet Union was only being formed, it was extremely important to bring up a new generation that would accept all the slogans, concepts and new reality of the Soviet state from a very young age. So almost all children’s books in the country were published by the State Publishing House (GIZ) and were notable for their purely communist rhetoric, educating young readers on the benefits of being a communist and the offspring of workers.

“The objective of the symposia has been to examine relationships between the verbal and visual idioms of Soviet illustrated books for young readers,” said Keenan, who selected the books for digitizing along with two Princeton faculty members – Serguei Oushakine and Katherine Hill Reischl.

“With this in mind, a complex of criteria were used in the prioritization of the books from the Cotsen collection to be digitized.”

From pioneers to experiments

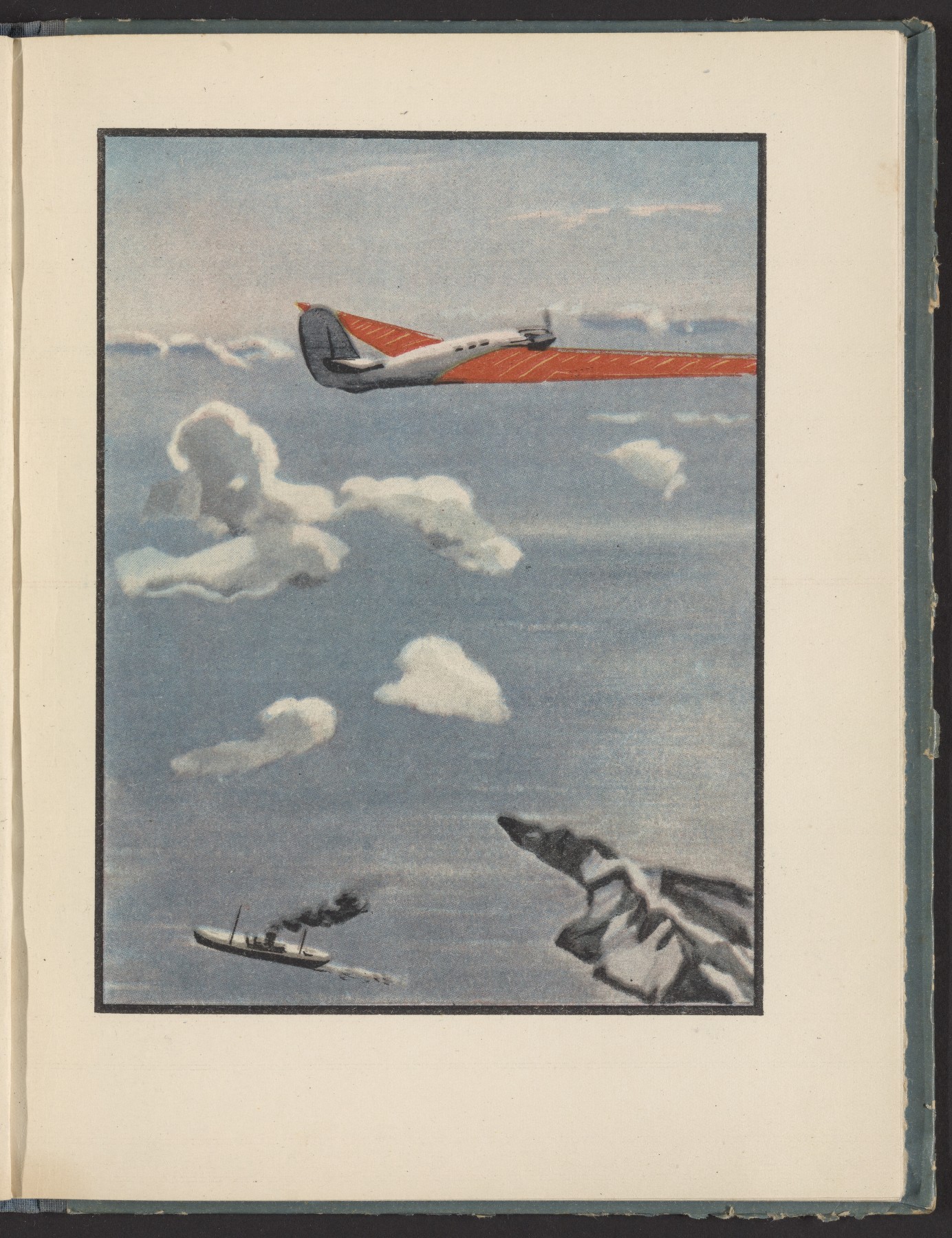

All the books are in Russian. The collection features Across the Pole to America, a rare example of an account of the first flight from Moscow to the United States via the North Pole, made by cult pilots Valery Chkalov, Georgy Baidukov (author of the book) and Alexander Beliakov. The book was published in Moscow and Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) and has illustrations by iconic Soviet artist Alexander Deineka.

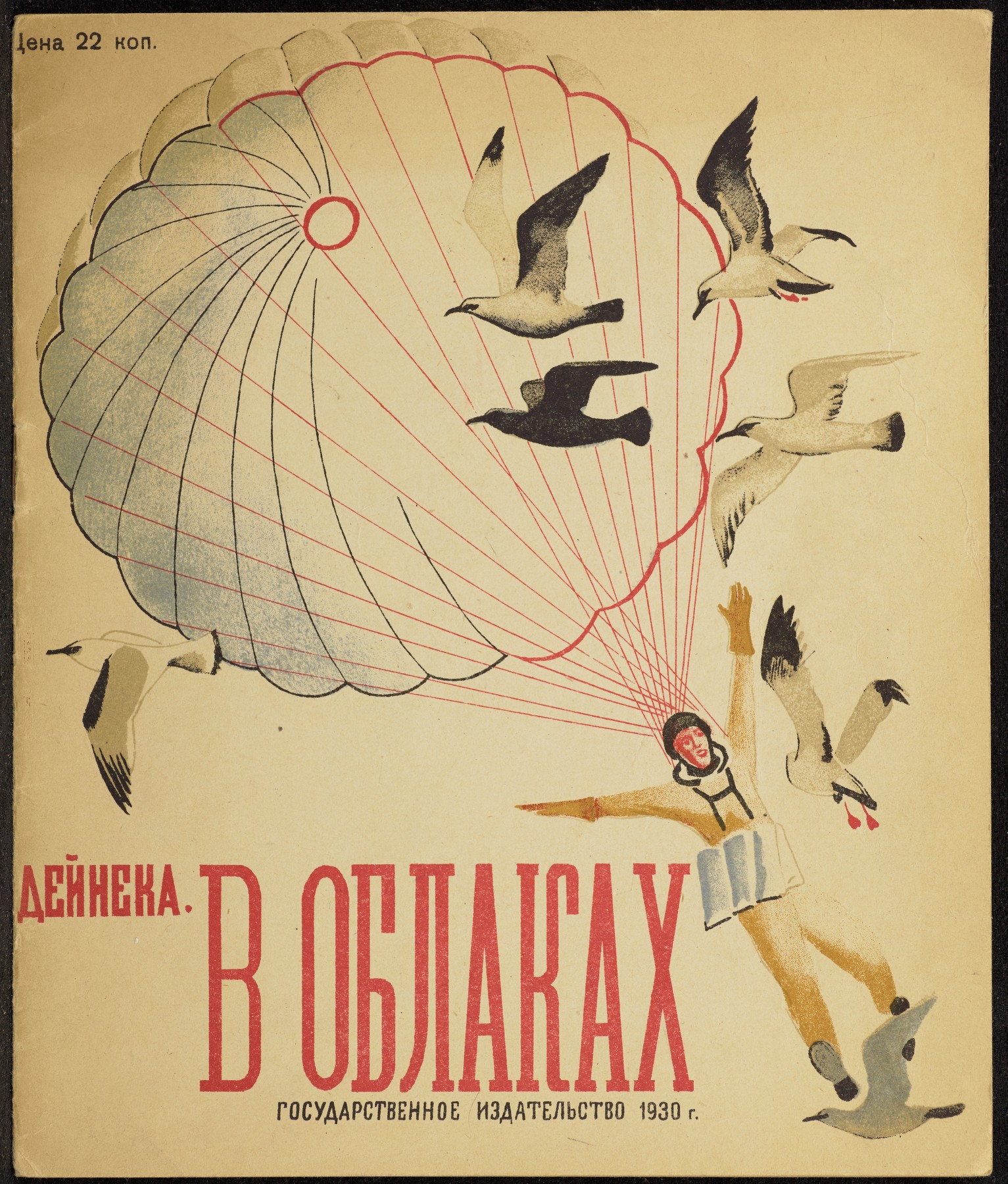

The collection also features Deineka's solo books of illustrations – Parade of the Red Army and In the Clouds.

'Across the Pole to America' (with illustrations by Alexander Deineka). Source: Princeton University Library

'Across the Pole to America' (with illustrations by Alexander Deineka). Source: Princeton University Library

'Parade of the Red Army' (with illustrations by Alexander Deineka). Source: Princeton University Library

'Parade of the Red Army' (with illustrations by Alexander Deineka). Source: Princeton University Library

'In the Clouds' (with illustrations by Alexander Deineka). Source: Princeton University Library

'In the Clouds' (with illustrations by Alexander Deineka). Source: Princeton University Library

Users of the resource can also read books by beloved children’s poet Agniya Barto, such as Pioneers – a poetic story about a pioneer named Fedya and the life and activities of Soviet scouts: camping, marches with communist red flags and holidays with other children of the model Soviet citizen – the worker.

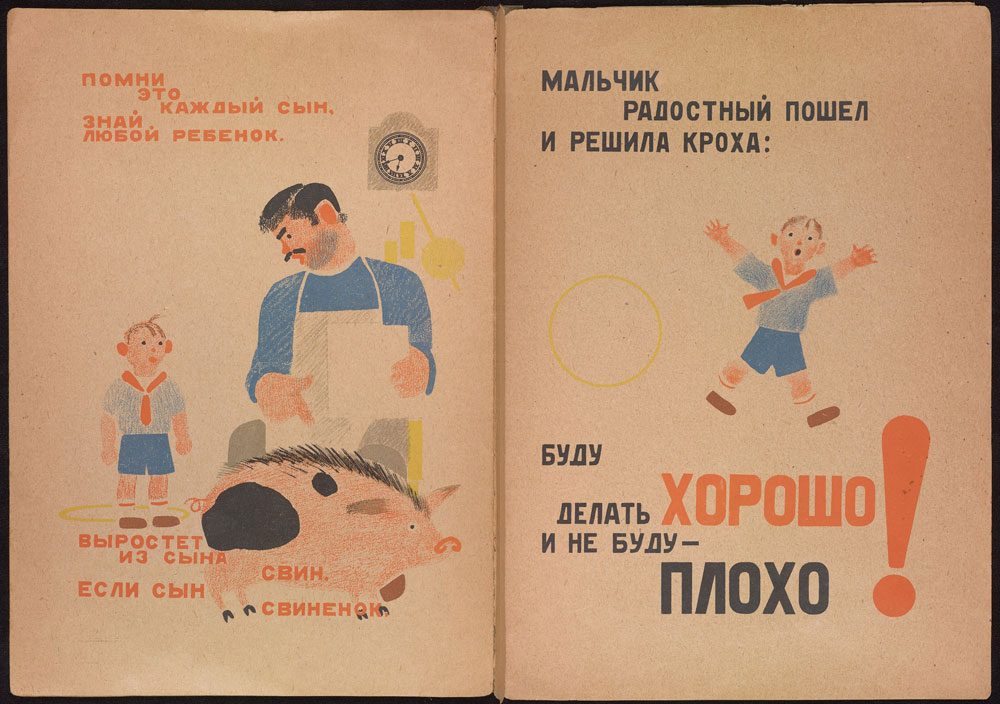

Vladimir Mayakovsky was famous not only for his revolutionary poetry but also as a children’s poet. Almost every Soviet and Russian kid remembers from an early age his poem What is Good and What is Bad?, in which he explains that walking in the rain and thunderstorms is bad, cleaning your teeth is good, fighting with the boys is bad, while studying is good.

A collage from Mayakovsky's poem 'What is Good and What is Bad?'

A collage from Mayakovsky's poem 'What is Good and What is Bad?'

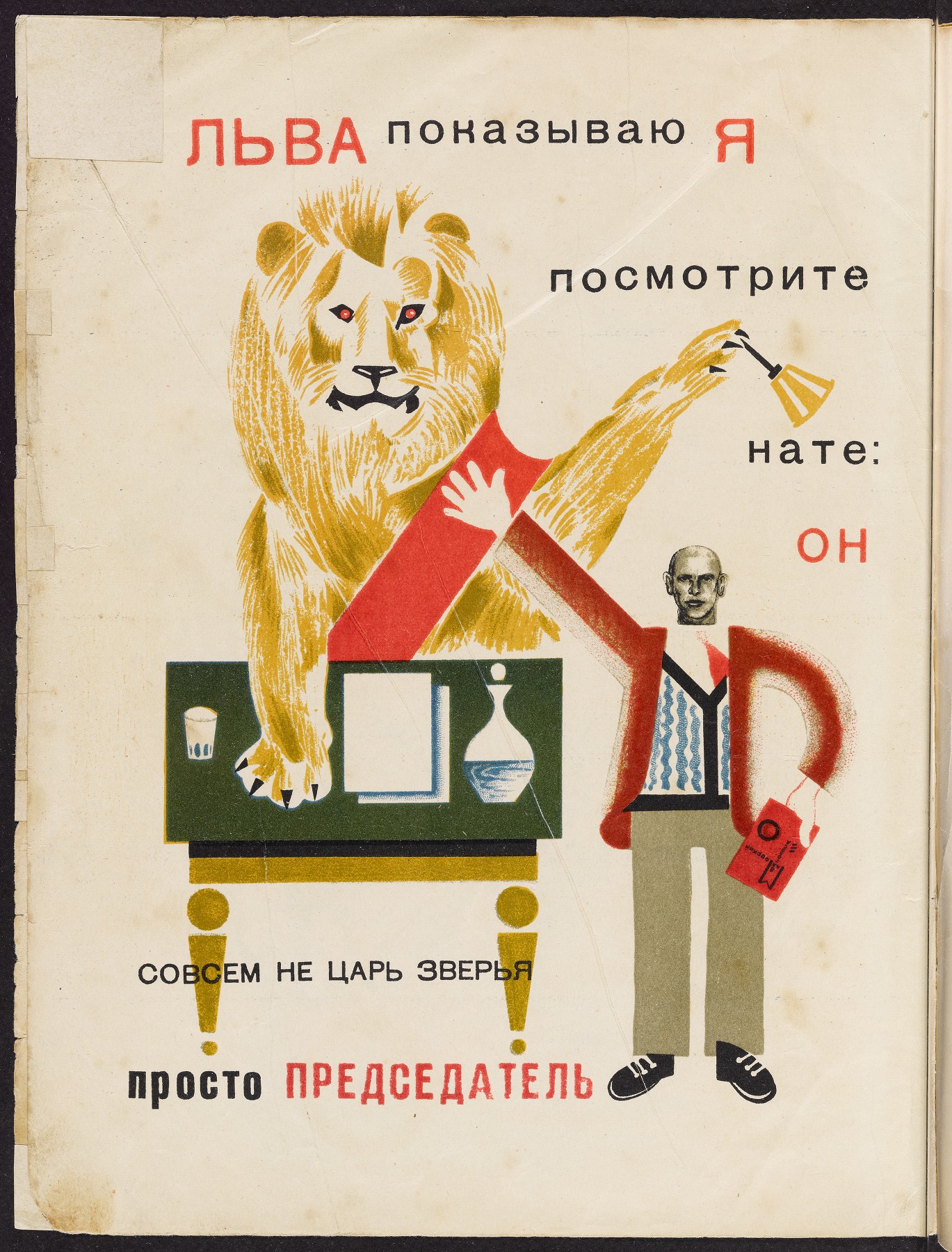

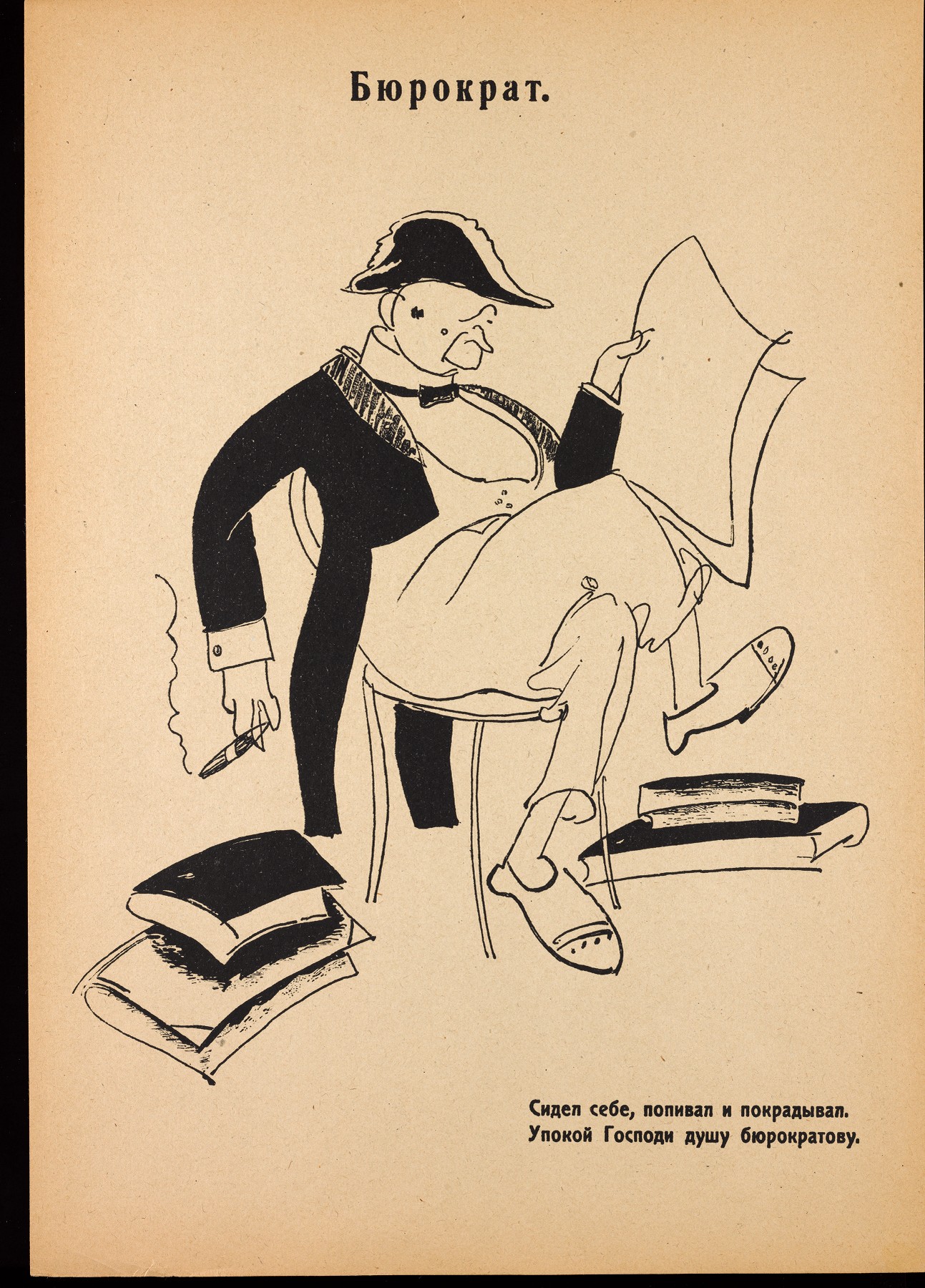

Princeton has also digitalized Mayakovsky's entertaining book about animals, Whatever Page You Look At, There's An Elephant Or A Lionessand a book titled October 1917-1918: Heroes and Victims of the Revolution, in which the “good guys,” – a worker, a Red Army soldier, a sailor, a seamstress – are compared with the “bad guys”: a factory owner, a landowner, a rich farmer, a priest, a merchant and others.

Vladimir Mayakovsky. Whatever Page You Look At, There's An Elephant Or A Lioness. Source: Princeton University Library

Vladimir Mayakovsky. Whatever Page You Look At, There's An Elephant Or A Lioness. Source: Princeton University Library

Red Army soldier, a hero from 'Heroes and Victims of the Revolution'. Source: Princeton University Library

Red Army soldier, a hero from 'Heroes and Victims of the Revolution'. Source: Princeton University Library

Bureaucrat, a victim from 'Heroes and Victims of the Revolution'. Source: Princeton University Library

Bureaucrat, a victim from 'Heroes and Victims of the Revolution'. Source: Princeton University Library

There are also works by Samuil Marshak, an acclaimed Soviet children’s writer and translator, absurdist writer Daniil Kharms and many other talented literary figures.

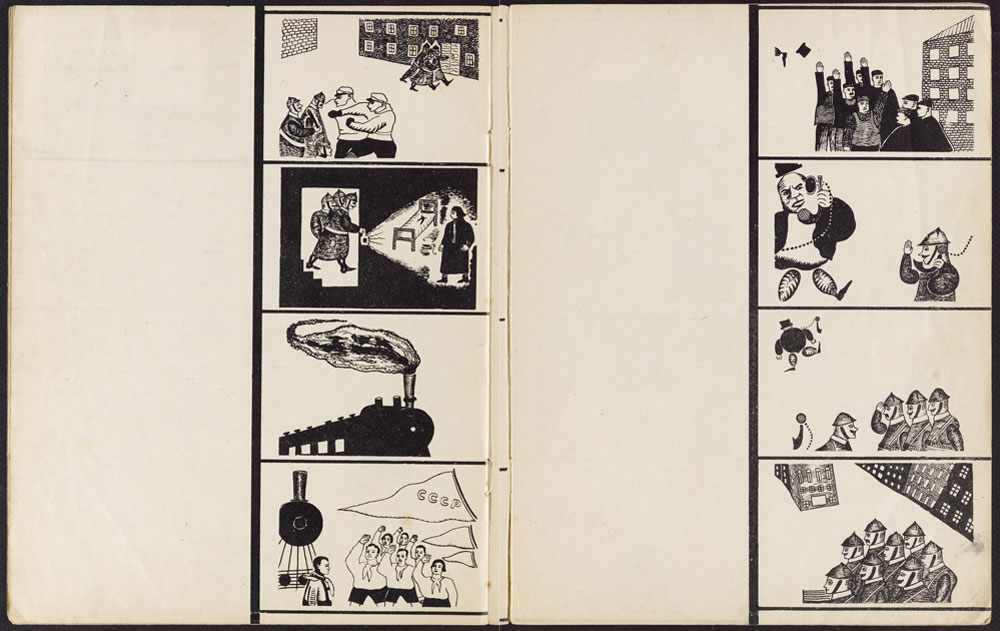

Like Mayakovsky and Kharms, many authors rejected the usual forms of literature and art, so there is an interesting example of an experimental movie-book with slides, titled A Book-Film-Performance About How the Pioneer Hans Saved the Strike Committee.

A collage of pages from the movie-book. Source: Princeton University Library

A collage of pages from the movie-book. Source: Princeton University Library

Princeton would like to continue the digitizing and even to undertake the translation of the Russian texts into English to expand the audience for this material.

Read more: How Dr. Dolittle became Dr. Aybolit

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox