'Work, build and don’t whine': Who were the Soviet superwomen?

Aleksandr Deineka‘Work, Build and don’t Whine’, 1930.

The City Museum, St. Petersburg

V. Spassky, ‘Mothers, Don’t Kiss your Children on the Lips and Don’t Let Anyone Else Kiss Them’, 1921–1927. Source: The City Museum, St. Petersburg

When you think of women in the Soviet Union, who do you see? Was she a communist, a worker, a wife, a mother? Or maybe she’s a soldier or a cosmonaut? Soviet women were all of this and more. GRAD Gallery in London is arranging a special program dedicated to the legacy of these “superwomen” with an exhibition, talks, film screenings and other events.

Until September 17 the gallery will feature ceramics, film, photography, photomontage, postcards, posters and sculpture from Soviet propaganda as part of an exhibition called “Superwoman: ‘Work, build and don’t whine.’” This was a slogan used to compel women to feel invested in the new communist order.

Women’s role in Soviet history is crucial

Women were heavily involved in the first revolution of 1917 in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg). On Women’s Day, February 23 (March 8 using the updated calendar), women joined a group of factory workers to protest food rationing by the tsarist government. In March 1917 Russia became the first major world power to grant women the right to vote and legalized abortion. Furthermore, the Soviet Union’s first constitution, published in 1923, officially recognized the equal rights of women, including equal pay.

After the foundation of the Soviet Union, revolutionary Lev Trotsky began to create the image of the “man of the future” and that of a “superwoman.” Just like men women had to be equally selfless, educated, healthy, muscular and enthusiastic in spreading the socialist Revolution. At the same time Soviet women were also pushed to continue bringing up their families and running their households.

N. Krupskaia and K. Zetkin attending the Presidium of the III All-Russian conference on pre-school education’, 1926 Gravure print on coated paper. Source: The City Museum, St. Petersburg

After World War I and the Civil War in Russia, the ratio of women to men grew substantially. By 1926 there were only 71 million males for nearly 76 million females.

Therefore much of the burden of helping Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in his economic goals of rapid industrialization fell on women. The number of women in the workforce jumped more than fourfold from nearly three million in 1928, when Stalin announced his first industrial Five Year Plan, to over 13 million in 1940.

These events, coupled with the enormous losses during World War II, meant that women of working age heavily outnumbered their male counterparts by a staggering 20 million after the war. As many as 57 percent of those active in the labor force between 40 and 50 years of age in 1959 were women. It became the norm for women to work outside the home.

Artist Unknown, ‘Let’s liberate women from the kitchen slavery for the work in socialist industry. Let’s organise amateur canteens’, c. 1927. Source: The City Museum, St. Petersburg

“Soviet women faced two major challenges: they were under pressure to both work long hours and at the same time they had to help Russia to expand its population by producing as many children as possible,” the exhibition curator Dr. Natalia Murray told RBTH.

Since Russia had always been a patriarchal society, women had to juggle work with all their usual responsibilities at home without relying on their husband's help.

“The situation has not improved much today,” Murray says. “However, one positive aspect of women in Russia gaining equal rights with men as early as 1920s is that for almost 100 years women were encouraged to get a good education… [so] they are now much more integrated into the Russian economy than women in many Western European countries.”

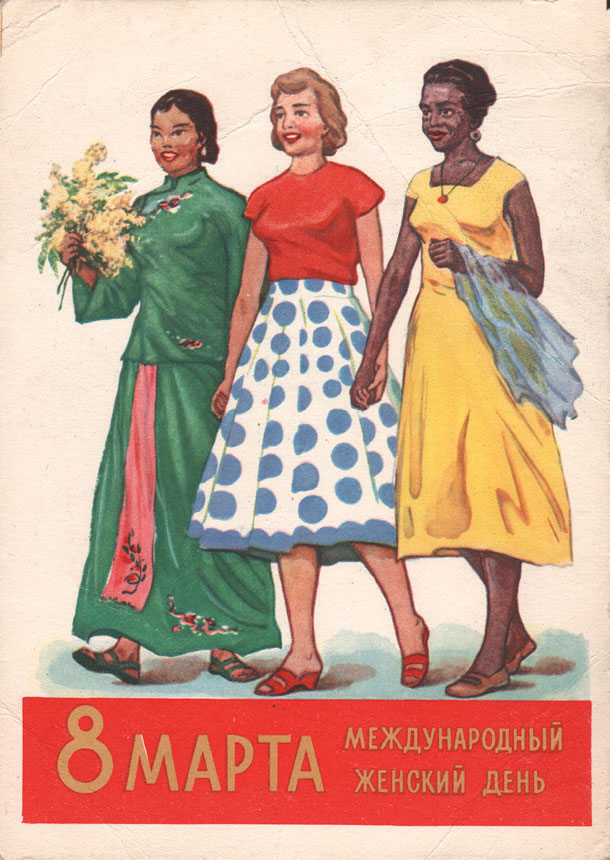

V. Stekolshikov, ‘8th of March – International Women’s Day’, 1959, Source: The City Museum, St. Petersburg

The image of women in propaganda

The exhibition takes the stories of the “superwomen” in official propaganda and juxtaposes them with the everyday reality of millions of Soviet women and poses the question, what does it mean to be truly liberated?

One of the main highlights is a bronze miniature version of Vera Mukhina’s iconic sculpture of the “Worker and Kolkhoz Woman,” which is on loan from Moscow’s Tretyakov State Gallery. One of the Soviet Union’s most significant female artists, Mukhina originally created her monumental sculpture for the 1937 Paris World Fair.

Other highlights include a poster by Aleksander Deineka, one of the leading proponents of avant-garde art for the proletariat, as well never-before-exhibited archival footage, documenting the “Sovietization” of women in the outlying Soviet republics.

Aleksandr Deineka ‘Work, Build and don’t Whine’, 1930. Source: The City Museum, St. Petersburg

Aleksandr Deineka ‘Work, Build and don’t Whine’, 1930. Source: The City Museum, St. Petersburg

Work, build and don't whine!

To the new life the path we’ll assign

An athlete you needn’t be

But being physically fit – is a must.

Filming Soviet women

The filmography part of the exhibition was curated by Thea Film, a company set up to develop film projects focusing on human issues across diverse cultures.

Dolya Gavanski, the head of Thea Films, says that there are several highlights. Gavanski says that the archival footage of women participating in the February Revolution, the work of the Zhenotdel (Women Section) in the 1920s and images documenting the liberation of women from Central Asia provide a sense of the sheer scope and scale of work that women undertook across the Soviet Union.

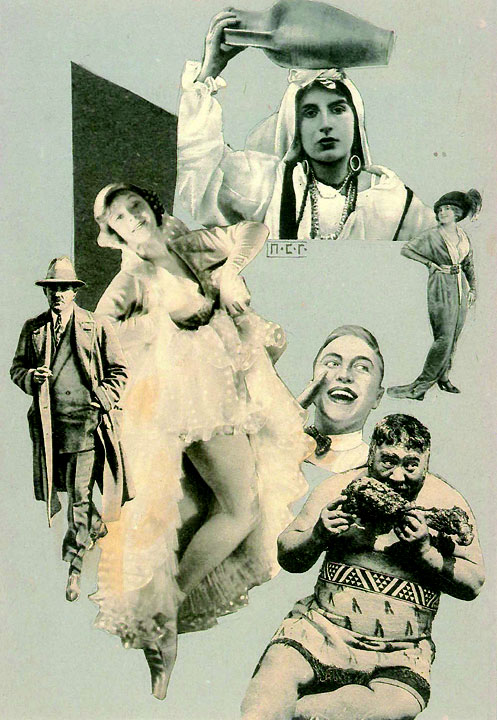

Piotr Galadschev Woman with a Jug, 1924, Source: Alex Lachmann Collection

“I don’t think it is possible to talk about one type of a Soviet woman,” Gavanski told RBTH. “Even the ideals changed across time and with it the official image of the perfect woman.”

“The disparity between reality and propaganda sometimes verged on the absurd and even the images in themselves often carry certain discrepancies,” Gavanski said. “These various layers are very interesting to explore.”

Pictured: A Christian Dior model in Moscow, 1959. Source: by Howard Sochurek/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Read more: Power and architecture: London’s Calvert 22 unveils its new season

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox