Natan Altman, Portrait of Poetess Anna Akhmatova, 1914, State Russian Museum

Global Look PressAnna Akhmatova strongly disliked the word “poetess,” especially when applied to her. For she was a poet. The depth of individuality and expression of her poems is simply astounding. A sense of frivolity, including numerous trysts, combined with incredible strength of mind and firmness of character enabled her to survive the terrible years of repression, the loss of her husband, the arrest of her son, and the printing ban on her poems.

The portraits of Anna Akhmatova are myriad. Her striking appearance, slender neck, languid eyes, slightly humped trademark nose, and austere fringe were the perfect muse. Nathan Altman, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Zinaida Serebryakova, Yuri Annenkov, and many other artists all created haunting portraits of her, tinged with tragedy. She herself in her poems created the image of a fragile, mournful woman, like in one of the most famous works:

Under a dark veil she wrung her hands…

‘What makes you grieve like this?’

I have made my lover drunk

With a bitter sadness. (1911)

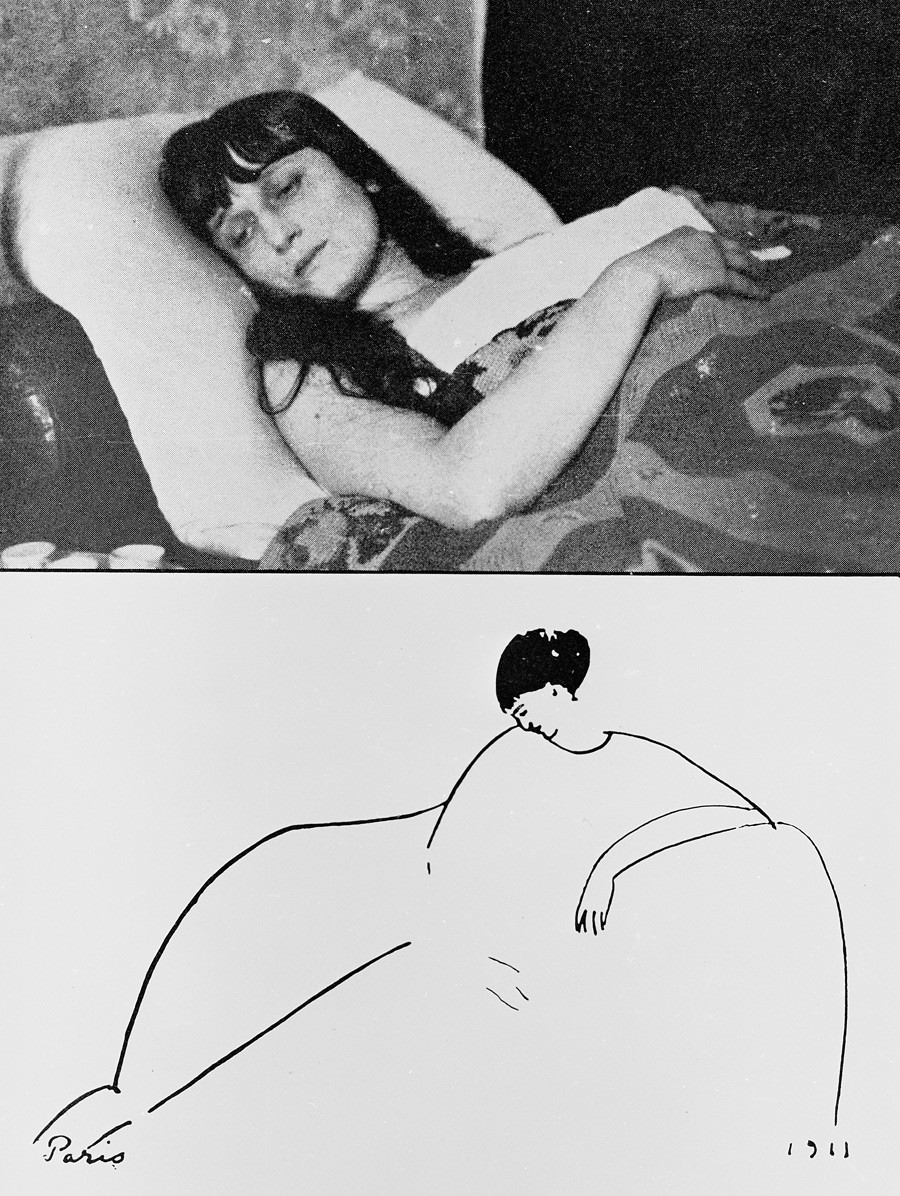

Italian Amedeo Modigliani even captured Akhmatova nude. Rumors swirled about an affair, yet, despite their mutual affection, Anna claimed they were just friends. They met while she and her husband, fellow poet Nikolai Gumilyov, were honeymooning in Paris, and met up for long strolls around the city together.

Above: Anna Akhmatova circa 1920, below: the drawing of her by Amadeo Modigliani, 1911

Getty ImagesAs for artist Boris Anrep, Anna really did have an affair. She dedicated more than one poem to him, while he depicted her in his famous Compassion mosaic in the lobby of London’s National Gallery, where she is surrounded by the horrors of war.

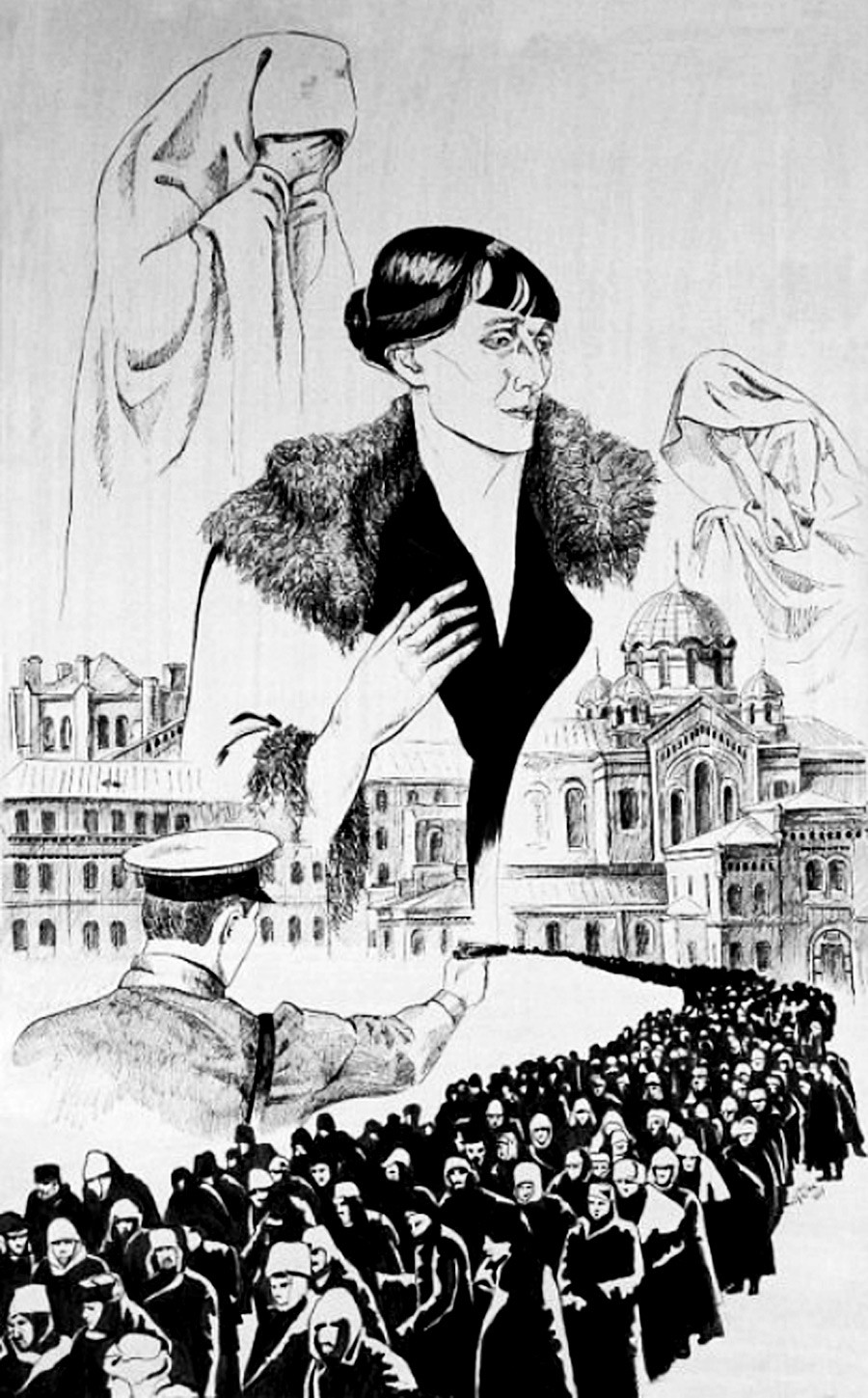

Illustration for Akhmatova's 'Requiem'

Archive photo“Husband in the grave, son jailed,/Please offer a prayer for me,” writes Akhmatova in one of her most famous poems, Requiem (1934-1963). Akhmatova’s lyrics generally reflect the entire 20th century, plagued by revolution, political terror, and war.

Like her, Akhmatova’s first husband, poet Nikolai Gumilyov, was a leading light of the Silver Age. In 1921, he was arrested and executed for alleged anti-Bolshevik activity.

The couple’s son Lev, a prominent historian, was also arrested during the Stalinist purges, denounced for “counter-revolutionary agitation,” and sent to the gulag. Akhmatova’s notes in which she writes about the “time of prison queues” have been preserved. In sweltering heat and punishing cold, hundreds of women stood at the door of the KGB building in Leningrad in the hope of a single word about their arrested husbands and sons. Every day, for months on end, they came and stood, only to be refused information about their whereabouts. The lucky few were allowed to leave a message, but with no guarantee that it would be passed on. Requiem is, in essence, a hymn of mourning to these harrowing lines of distraught women, with lips blue from the cold, ready to throw themselves at the feet of the hangman simply to learn the fate of their loved ones.

Akhmatova also penned one of the most powerful anti-Stalin poems to have survived, albeit less well-known than Mandelstam’s “We live without feeling the country beneath us.”

Imitation of Armenian (1931)

I shall come into your dream

As a black ewe, approach the throne

On withered and infirm

Legs, bleating: ‘Padishah,

Have you dined well? You who hold

The world like a bead, beloved

of Allah, was my little son

To your taste, was he fat enough?’

Anna Akhmatova, photo by Moisei Nappelbaum

Getty ImagesDuring the Leningrad blockade, Akhmatova remained in the city and even sewed sandbags for the trenches. She and fellow poet Olga Bergolts read their poems on the radio to keep up the spirit of Leningraders (“The hour of courage has struck on our watches,/And courage will not abandon us”).

After the war, the Communist Party decreed that Akhmatova was a representative of “empty poetry devoid of ideology, alien to our people.” The communists did not like what they saw as the decadent spirit and excessive aestheticism of her verse. Party leader Zhdanov described her poetry as far removed from the people with its “trifling ordeals and religious-mystical eroticism.”

As a result, her poems were not printed anywhere, and instead were distributed among the intelligentsia in a type of early samizdat: people learned them by heart, wrote them down, gave them to friends, and burned the notes. Keeping “harmful” poems was a dangerous game.

Akhmatova herself miraculously escaped arrest, apparently due to her prominent position.

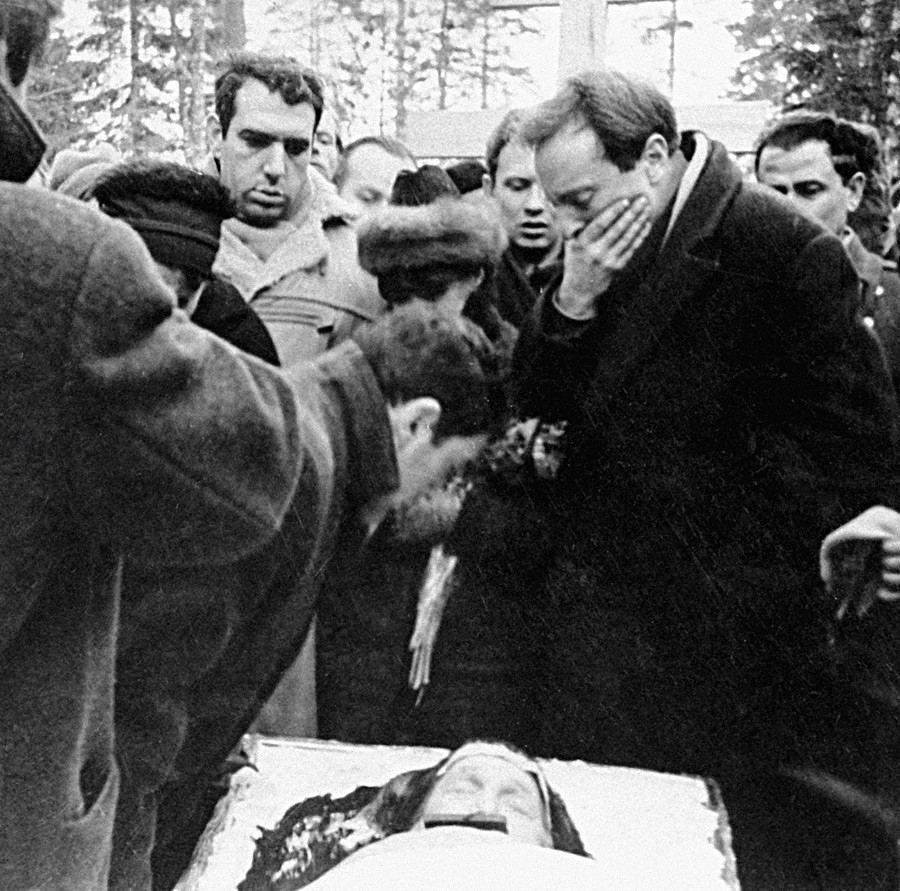

Poets Joseph Brodsky (standing right) and Yevgeny Rein (center) during the funeral ceremony for Anna Akhmatova

SputnikEven in her autumn years, Akhmatova remained a beacon for legions of admirers eager to make her acquaintance and partake of the Silver Age generation, of which she was perhaps the only one to glimpse the post-Stalin 1950s and beyond.

Among her younger friends were four poets who later made waves in the world of literature: Dmitry Bobyshev, Anatoly Nayman, Yevgeny Rein, and perhaps the most famous, Joseph Brodsky. They jokingly referred to themselves as “Akhmatov’s orphans” – for them, she was not just a poetic, but spiritual authority, and her death in 1966 was a personal tragedy for each.

Brodsky, incidentally, was not a fan at first – he merely took advantage of an offer to meet her. But one line of her verse (“This cruel age has deflected me, like a river from its course.”) opened his eyes to the full scale of her persona. As he said himself in an interview: “No one and nothing ever taught me to understand and forgive everything — people, circumstances, nature, indifference of the higher spheres – like she did.”

Anna Akhmatova at her working desk in Leningrad, 1964

asily Fedoseyev/TASSHer phrase about Brodsky’s arrest and exile in northern Russia on charges of “social parasitism” became famous: “What a biography they are creating for our redhead.” She also said that he was one of the most talented poets whom “she herself raised.” Brodsky was highly flattered by this phrase.

Anna Akhmatova (front row center) after receiving an honorary degree, Oxford, June 7, 1965

Getty ImagesA year before her death, at the age of 75, when her poems had not been published in her homeland for 18 long years, Akhmatova was invited to England and presented a PhD gown from Oxford University. In a ceremonial speech, it was said that, “this majestic woman is rightfully called by some ‘the second Sappho.’”

English newspapers, which actively covered the visit of this great poet who had been “rejected in the Stalin era,” wrote how she was deeply moved by such international recognition.

QUIZ: Test your knowledge of Russian poetry

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox