There are very few humorists among Russian writers - the majority see their mission as reflecting deeply upon the destiny of Russia and the meaning of life. But Zoshchenko, like his great predecessors Nikolai Gogol and Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, issued a challenge to society and subtly ridiculed the new class of people that appeared after the 1917 Revolution.

"From the point of view of party members, I am a man without principles. So be it. For my part, I will say the following about myself: I am not a Communist, I am not a Socialist Revolutionary and I am not a monarchist - I am just a Russian," Mikhail Zoshchenko wrote in his 1922 autobiography.

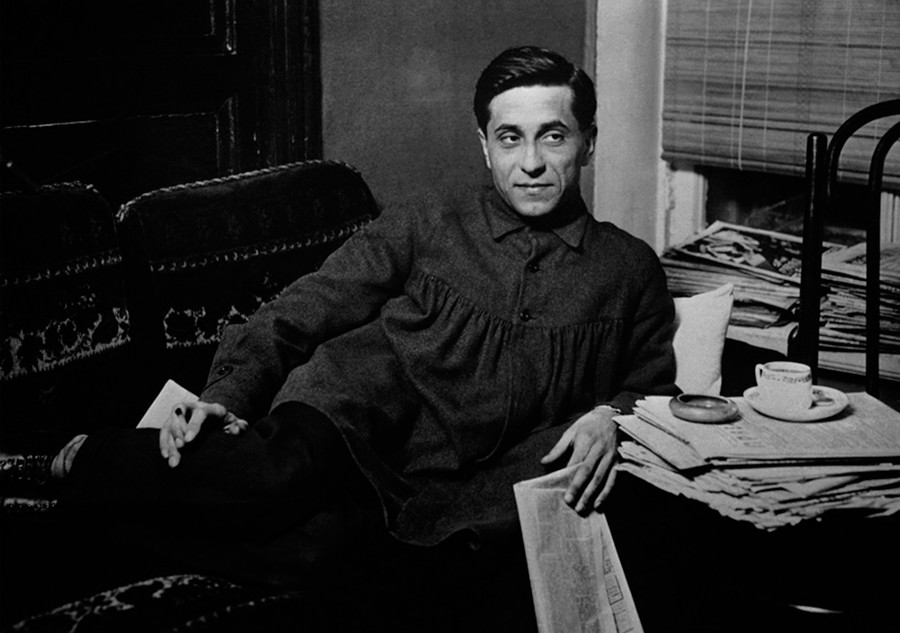

Mikhail Zoshchenko

Vladimir Presnyakov/Anna Akhmatova state literary memorial museumNonetheless, during the Civil War Zoshchenko fought on the side of the Reds and was sympathetic towards the Bolsheviks. "In their general thrust the Bolsheviks are closer to me than anybody else. And so I'm willing to bolshevik around with them." Like the Bolsheviks, Zoshchenko didn't believe in God and even regarded Orthodox Christian rites as ridiculous; he loved the Russia of the "muzhiks'" [peasants]. However, he openly declared he was not a Marxist and would never become one.

He ironically observed that in his time it was hard to be a writer: "These days a writer must have an ideology." Unfortunately, the lack of ideological content in his works was to play a cruel joke on him.

Zoshchenko especially made fun of the new ruling class - the workers and their "petit bourgeois pretensions". For instance, in many stories he places his characters in a theater and the very fact that they are there is already comical. They don't appreciate art, and deep down despise it, but they want to be seen as cultured. At first such characters behave themselves, but then, without fail, they make a scene.

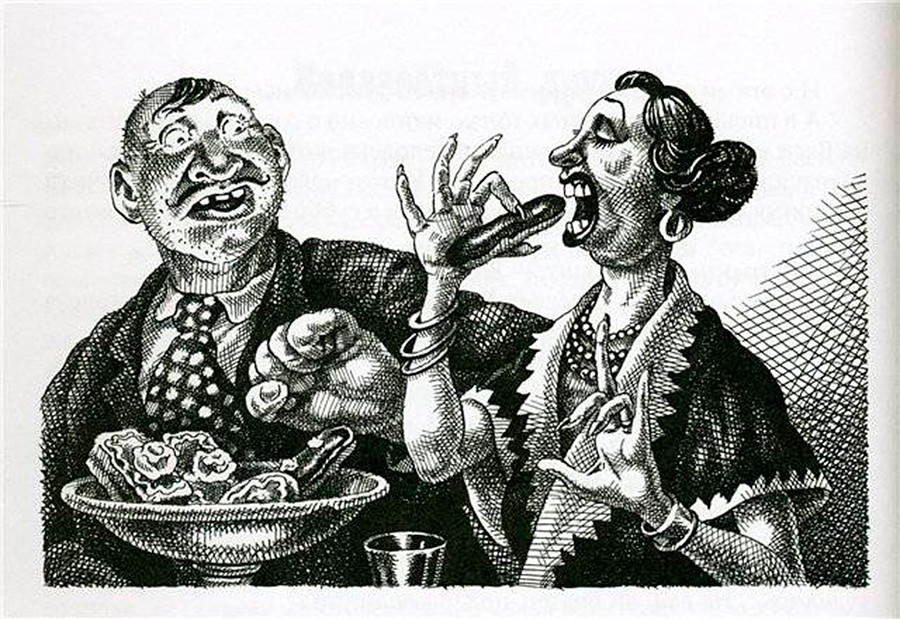

Illustration for 'The Lady Aristocrat' short story by artist Sergei Lemekhov

Mikhail Zoshchenko/Drofa Plyus, 2006Thus, in his famous short story The Lady Aristocrat, the hero tells friends that one should beware of "dames who wear hats" and have gold teeth - one such lady dragged him to the theater. "I, like a goose, or an unclipped bourgeois, fussed around her and proposed: If you want to eat a cake don't be bashful. I'll pay." In the end, the lady ate three cakes during the interval. And, realizing how much he would have to pay for them, the wretched hero stops being a "goose" and starts shouting: "Put it back!". Furthermore, Zoshchenko deliberately has his character use vulgar and abusive language. [English translation from: Mikhail Zoshchenko, Nervous People and Other Satires, translated by Maria Gordon and Hugh McLean. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1963, pp 127-130]

And in the short story The Crisis (1925) the writer mocks the policy of "packing people together" pursued by the Bolsheviks (the same thing is also described by Mikhail Bulgakov in his famous Heart of a Dog). New residents were installed in the numerous rooms of apartments formerly belonging to the nobility - they were frequently members of the proletariat (or people of a similar cultural level). The hero of the story is allocated a spacious… bathroom. And everything would have been fine if it weren't for the fact that the other residents came in to wash each day… "There were thirty-two of these scoundrelly tenants. And they all cursed terribly. Even threatened to bash my face in." [English translation: ibid., p. 139]

A still from the movie 'It Can't Be'

Leonid Gaidai/ Mosfilm, 1975In 1975, the cult Soviet film director Leonid Gaidai shot a comedy - It Can't Be! - based on motifs taken from the works of Zoshchenko. It consists of three novellas and graphically portrays the NEP [New Economic Policy, 1921] era and the new people that it produced and their mores.

During World War I, before he had embarked on a writing career, Zoshchenko volunteered for the front and took part in fighting, for which he received numerous medals for bravery and distinguished service. But he also developed heart disease, which forced him to leave the army and earn a living as best he could in various jobs in several Russian towns: "In the course of three years I got through 12 towns and 10 professions." Subsequently he joined the Red Army as a volunteer, and took part in the Civil War, but he was again demobilized because of his heart. He was first published in 1922.

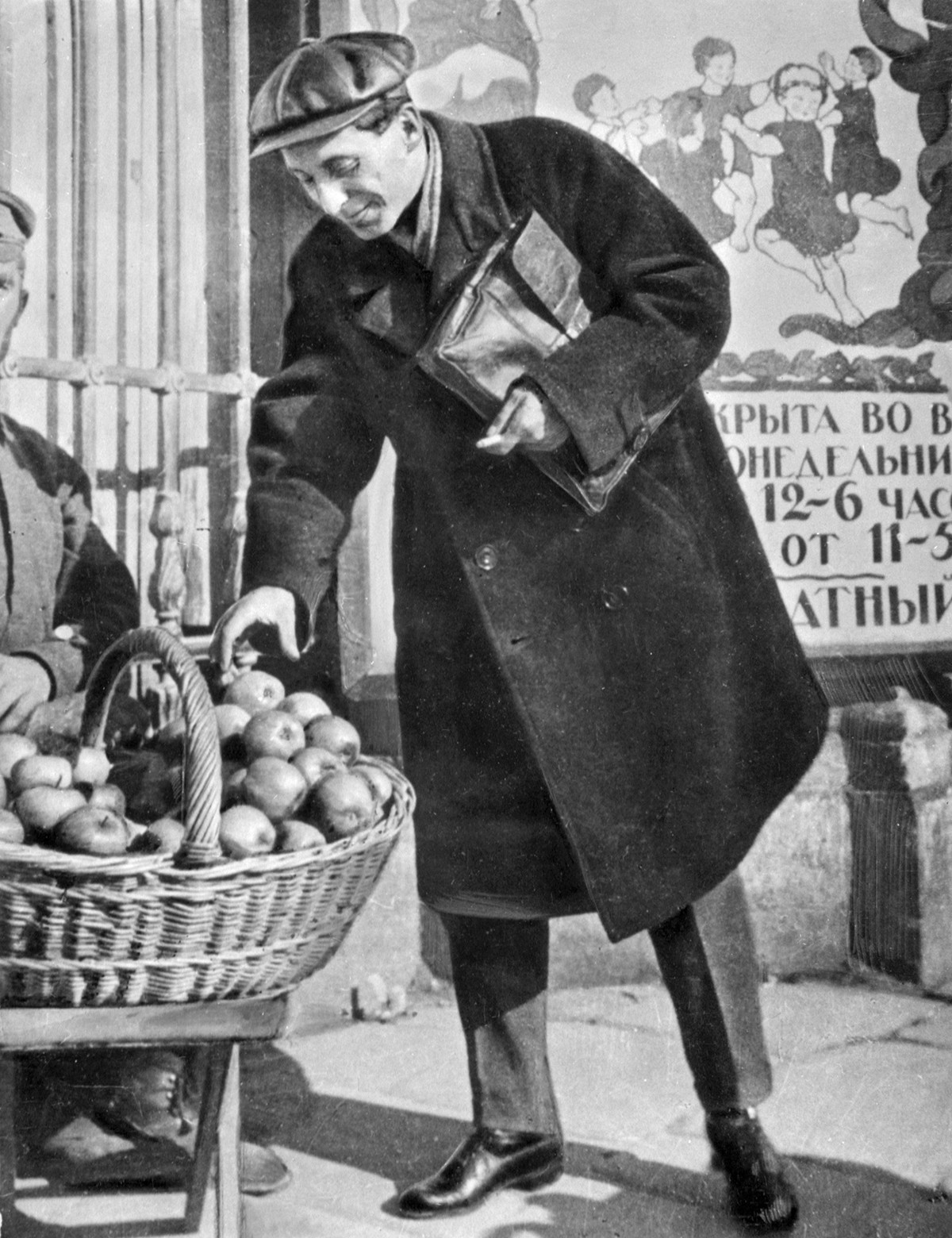

Mikhail Zoshchenko, 1916

Public DomainZoshchenko's stories, novellas and tales, and also his children’s stories about Lenin, enjoyed great popularity in the 1920s-30s and were published in enormous print runs. At the very start of World War II Zoshchenko wanted to enlist as a volunteer for the front again, but he was declared unfit and sent away with other evacuees. He took a suitcase of manuscripts and a small number of personal belongings with him.

During his time as an evacuee, Zoshchenko completed the autobiographical novella Before Sunrise, which he regarded as his most important work. In it the writer attempts to overcome and understand the cause of his melancholy, his psychological fears and neuroses. It is one of the first Russian psychoanalytical works. But it was not published in full in the Soviet period.

Mikhail Zoshchenko, 1923

Boris Ignatovich/SputnikAfter the war, in 1946, the party tightened censorship and closed down a number of journals. Zoshchenko was accused of behaving inappropriately during the war and having "hunkered down in the rear" and done nothing to help the Russian people. His satire was declared anti-Soviet.

"Zoshchenko portrays Soviet conditions and Soviet people in a twisted and caricatured manner, slanderously depicting Soviet people as primitive, ill-educated and stupid, with petty tastes and mores," said a party resolution of 1946. Zoshchenko was expelled from the Union of Writers - in effect, this meant he was barred from publishing his work and deprived of his livelihood.

He managed to eke out some sort of living doing translations. In 1954, at the insistence of some British students who had come to the USSR, the writer was summoned for a meeting with them. He publicly voiced his disagreement with the party resolution - and recalled that he was a war hero. He was then brought before a party meeting to repent.

The writer stood firm, however, and declared that he did not intend to ask the Soviet authorities for anything. "A satirist has to be a morally pure individual, and I have been humiliated like the lowest son of a bitch…"

He managed to obtain a small pension from the state in 1958, but he died of heart failure shortly afterwards.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox