As a multi-ethnic state, Russian literature has also benefited from the creative minds of the country’s many different national groups. For example, it was enriched by Jewish authors, some writing in Russian, though others wrote in Yiddish, the local Jewish language. Indeed, Russia’s highly diverse ethnic composition often makes one wonder about the extent to which national identity defines an author.

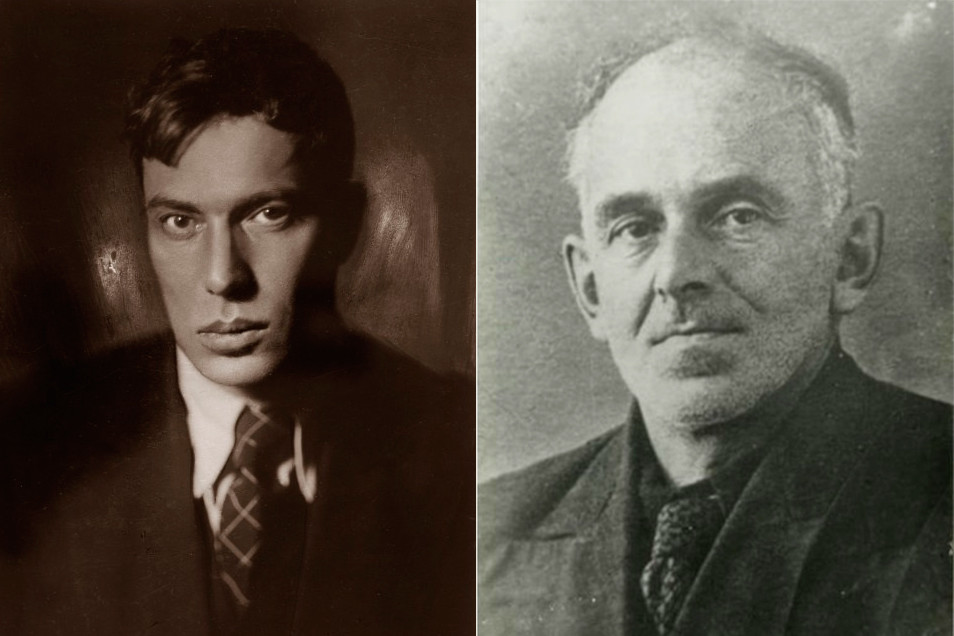

“Many believe that the language determines the national literature, and in most cases that’s true,” says Moscow-born Jewish author Semyon Reznik, now a U.S. citizen who still writes in Russian. “Pasternak was a Jew, but he considered himself a Russian writer. The same for Mandelstam and many others.”

Boris Pasternak (L) and Osip Mandelstam

Moisei Nappelbaum/Marina Stich archive; MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruAt the end of the 18th century, the Russian Empire acquired most of the world’s Jewish population with the annexation of Polish lands. While the Jews simultaneously prospered and faced persecution in 19th century Russia, few were active as Russian language writers. Prominent Tsarist-era Jewish authors, such as Sholom Aleichem, usually wrote in their native Yiddish. Later, in the Soviet period, Jewish writers almost exclusively wrote in Russian.

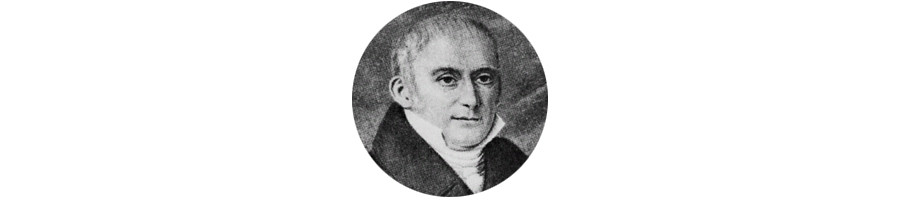

Russian-Jewish literature’s founder is Lev Nevakhovich (1778-1831), who in 1803 wrote a book titled The Cry of the Daughter of the Jews, which was meant as a defense of the Jews.

Russian Jewish authors often took on difficult and uncomfortable topics, such as the mass hysteria of anti-Semitism in Imperial Russia. Here’s a short list of some prominent Jewish novelists inspired by the experience of their people before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Near the end of Catherine the Great’s rule, Nevakhovich went to St. Petersburg as a businessman, but eventually became a writer. He is considered one of the first Jews to master the Russian language. A Jewish patriot, he wanted to show the Tsar that the Jews were upstanding and reliable citizens. The Cry of the Daughter of the Jews («Вопль дщери иудейской») was a sort of appeal to the Russian people, calling them to show tolerance and brotherly love toward Jews.

Nevakhovich wrote: “For centuries, the Jews have been accused by the peoples of the earth… accused of witchcraft, of irreligion, of superstition... All their actions were interpreted to their disadvantage and whenever they were discovered to be innocent, their accusers raised against them new accusations... I swear that the Jew who preserves his religion undefiled can be neither a bad man nor a bad citizen.”

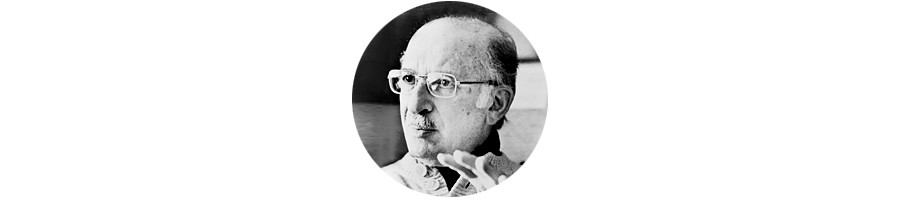

The novel by Bernard Malamud (1914-1986) was published in English in the U.S. in 1966. While a fictional account of a Jewish man in Imperial Russia, it accurately depicts how Jews lived in a highly anti-Semitic society. The book’s inspiration is the true-life story of Menahem Mendel Beilis, unjustly accused and jailed in what became known as the infamous ‘Beilis trial’ of 1913.

Beilis lived in Kiev, and in 1911 he was accused of murdering a Christian boy to use his blood in making Passover matzah. Even though jailed for over two years awaiting trial, Beilis resisted pressure to admit that he and other Jews were guilty. In 1913, an all-Christian jury acquitted Beilis.

Later, Beilis’ son David complained that Malamud plagiarized from his father’s memoir, a bold accusation considering that The Fixer had won a Pulitzer Prize for best novel. In addition, the son felt Malamud besmirched his father’s memory. Malamud’s main character, Yakov Bok, is “an angry, foul-mouthed, cuckolded, friendless, childless blasphemer”. The son countered that his father was “a dignified, respectful, well-liked, fairly religious family man with a faithful wife”. (Blood Libel: The Life and Memory of Mendel Beilis; editors Jay Beilis, Jeremy Garber and Mark Stein, 2011)

While Malamud denied the accusations, historian Albert Lindemann lamented: “By the late twentieth century, memory of the Beilis case came to be inextricably fused (and confused) with... The Fixer.”

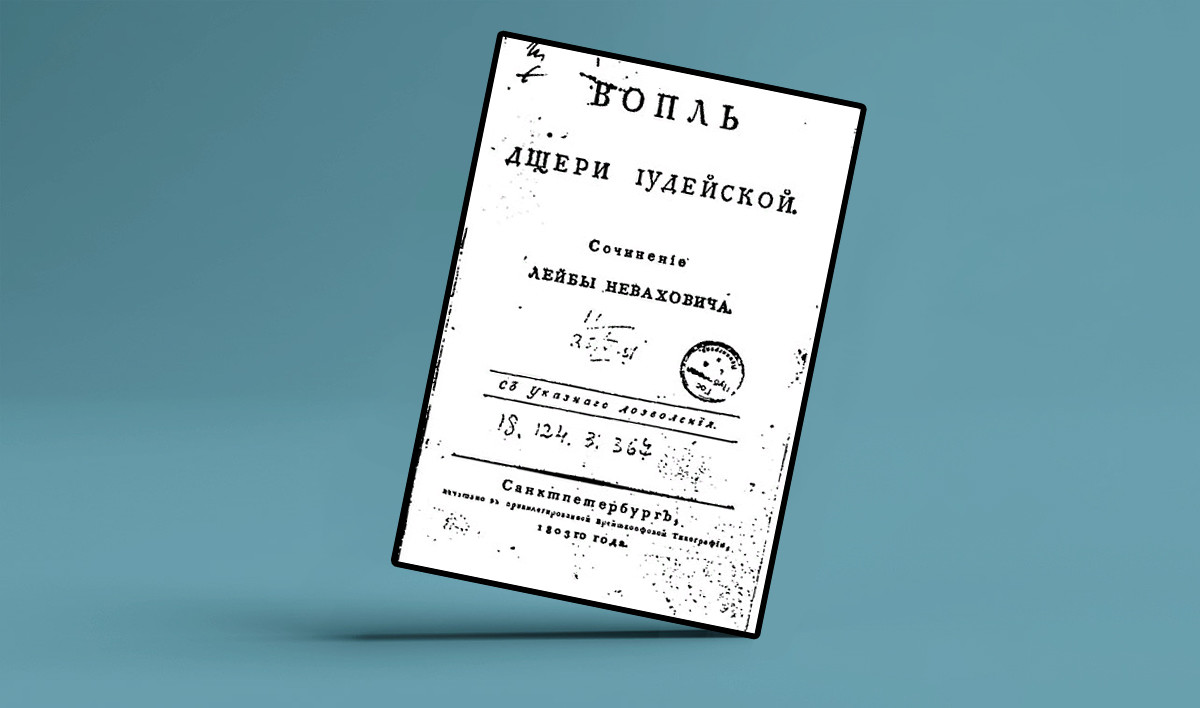

The most popular of all Yiddish writers, Sholom Aleichem (1859-1916) was born in a Jewish village near Pereyaslav, Ukraine. He wrote with humor and warmth about the Yiddish-speaking Jews of the Russian Empire and is considered to be sort of a ‘Jewish Mark Twain’.

Aleichem’s novel, Tevye and His Daughters, takes place in Imperial Russia in the late 19th century, but it’s better known today as the American musical ‘Fiddler on the Roof’, and the cinema version gave the world famous songs such as ‘If I were a Rich Man’ and ‘Sunrise, Sunset’.

Tevye the dairyman is one of the most vivid characters in the Jewish literary tradition. In the novel, he’s baffled that God gave him seven daughters, but no sons. Tevye loves them all dearly, and the daughters love their father, but as they grow up in a rapidly changing world, this family is confronted by various generational dilemmas that are familiar even today.

Anti-Semitism and pogroms eventually lead to a final dissolution of their world. Tevye, along with some of his family and neighbors, emigrate to the U.S.. By the way, such was also the fate of the author, who today is buried in New York City.

Written in the Soviet Union in 1956, this autobiographical trilogy by the Jewish author Aleksandra Brushtein (1884-1968) is barely known outside the Russian-speaking world. Set in Vilnius when this city was a part of the Russian Empire, it’s considered an adventurous coming-of-age story, as well as a historical and social tale.

“With biting humor, abundant self-irony and a deep appreciation of her past, Brushtein tells the story of her childhood and adolescence in Vilna at the turn of the 20th century,” said one reviewer in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz in October 2019.

The story’s main hero, Sasha Yanovskaya, confronts the quota system limiting Jewish enrollment to educational institutions; nevertheless, she finds a way to be admitted to a prestigious school for girls. She encounters dozens of fascinating characters, including the family’s servant, Yozefa, a pious Polish woman, as well as Hannah, an elderly Jewish pretzel vendor. As a teenager in the second book, Sasha witnesses the anti-Semitic trial of Jewish peasants falsely accused of making human sacrifices.

“It is hard to overstate just how much Aleksandra Brushtein’s autobiographical novel about Aleksandra (Sasha) Yanovskaya, a young Jewish girl growing up in Vilna at the turn of the century, was beloved by generations of Soviet children,” according to critic Yelena Furman. “In the Soviet Union, where it ran through many editions of tens of thousands of copies each, the trilogy achieved cult status.”

Based on an anti-Jewish pogrom in the Russia Empire in the 1820s, the historical novel Chaim-and-Maria is full of wit and sarcasm. In fact, the title, Chaim-and-Maria, is a parody of the name of the flower called ‘Ivan-da-Maria’ (Иван-да-Марья), which symbolizes Love.

Semyon Reznik wrote the novel in Moscow in the 1970s, but couldn’t find a publisher. The book was finally published in English in early 2020. During the Soviet era, Reznik was better known as the author of several books on scientists, including the “ideologically harmful” biography of great Soviet biologists, such as Nikolay Vavilov, who was murdered during Stalin’s rule.

Reznik, who emigrated to the U.S. in 1982, chose the Velizh case as the subject of his novel because it was one of the largest of nearly 200 blood libel cases against Jews in 19th century Europe. In April 1823, three-year-old Fedor, a Russian boy, was found murdered in a field outside Velizh, a small city in Vitebsk Province. More than 40 Jews were wrongly accused of the murder and arrested. Many eventually died in prison; others survived, but their lives were destroyed.

“The prejudices and persecution of the Jews in Russia was not so much a Jewish problem, but rather a Russian problem. It damaged the Russian spirit, culture and statehood,” said Reznik. “It’s too trivial to demonstrate that the Jews are suffering when they are persecuted. But what about the persecutors? That is why I tried to represent all layers of Russian society, from top to button.”

While the tragic events in the Velizh case are humorously and grimly described, Chaim-and-Maria’s ending leaves one deeply disturbed. Mass hysteria can often arise from the simple and primitive logic of rural folk and then easily promoted by corrupt bureaucrats, who pursue their own mercantile and political interests.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox