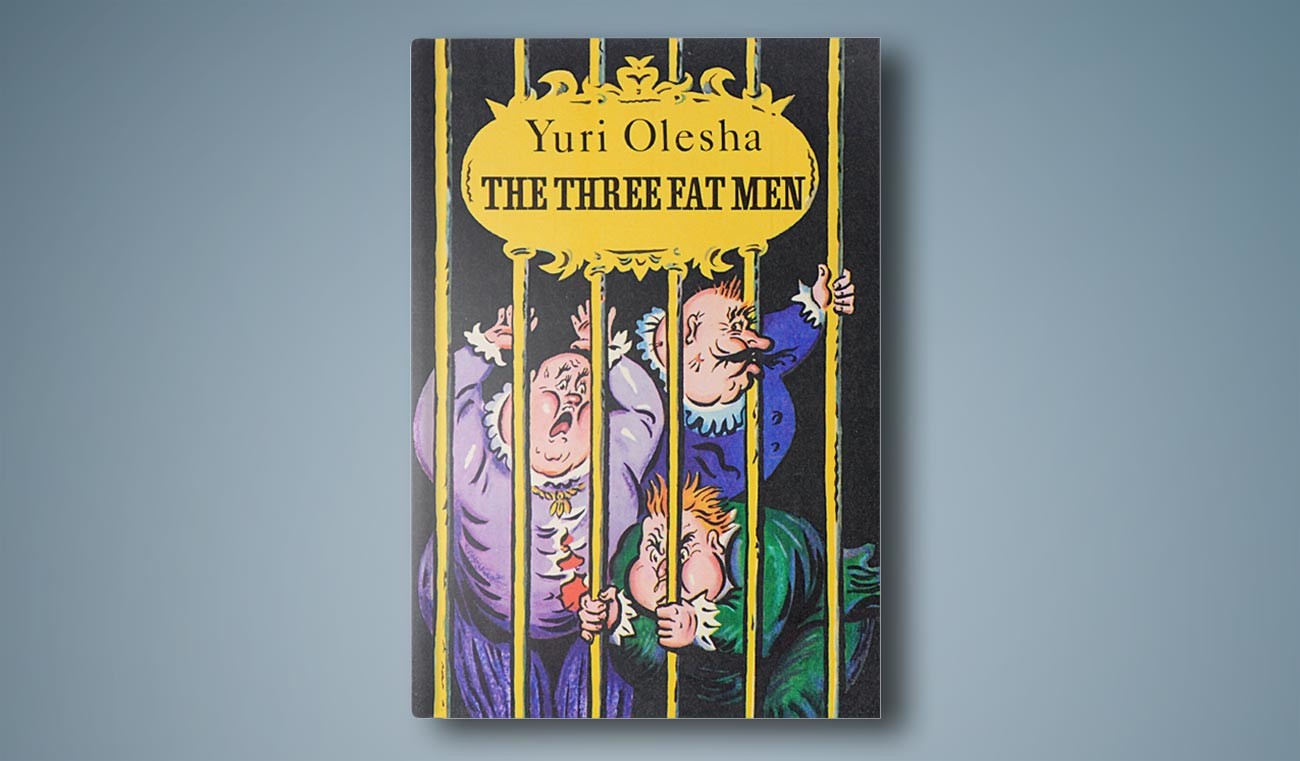

Although technically it’s a children’s book, it’s as accessible to adults as ‘The Hobbit’ or ‘Alice in Wonderland’.

‘The Three Fat Men’ carries obvious political connotations. The story is set in an unknown fictional country ruled by an insatiable and greedy aristocracy, who suppress the poor. Written in 1924, the story opens with an uprising led by the gunsmith Prospero, whose name is obviously an allusion to Shakespeare’s magician from ‘The Tempest’. The defeat of the rebels is a hint to the Revolution of 1905, while their triumphant victory at the end of the story metaphorically hails the October Revolution. No wonder one of Russia’s finest poets, Osip Mandelstam, praised Olesha’s “crystal-transparent prose, imbued with the fire of revolution”.

READ MORE: Yuri Olesha: The king of metaphors smashed by Stalin’s social realism

But, ‘The Three Fat Men’ is not a chronicle of bloody revolutions. It’s a tale of generosity, kindness and courage. Although Yuri Olesha believed that “the time of wizards has passed”, his story has all the magic of the classic European fairy tale worthy of Ernst Theodor Hoffmann or Hans Christian Andresen.

At the center of the story is a sweet young boy named Tutti. The poor thing is not allowed to make friends with any kids, his only companion is a doll named Suok. ‘The Three Fat Men’ has a powerful message about freedom and friendship. The moral is, things will change for the better if you just wait.

Legend has it, Olesha was looking out the window when he saw a girl aged about 13. She was reading Andersen’s fairy tales. Olesha then made a promise to himself to write the “best fairy tale in the world” and dedicate it to the girl. That pledge gave birth to ‘The Three Fat Men’.

READ MORE: Yuri Olesha: The king of metaphors smashed by Stalin’s social realism

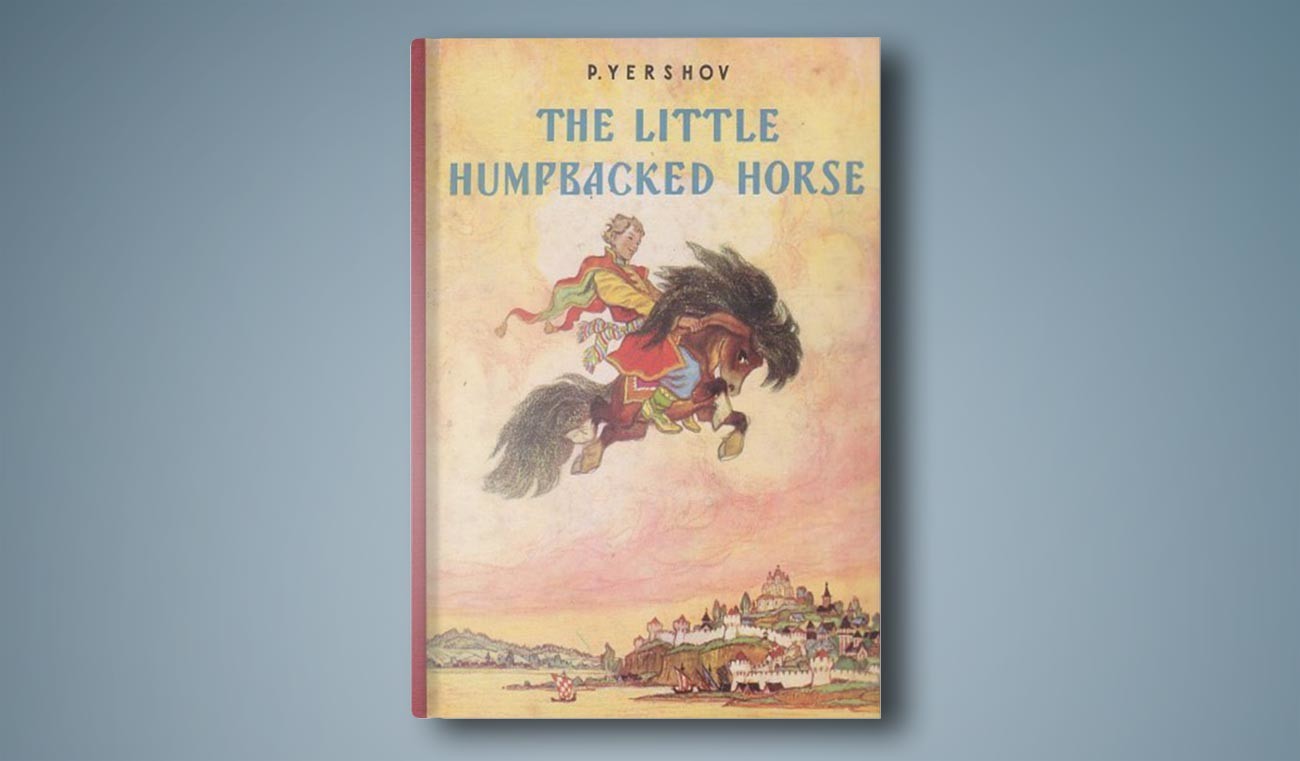

Ershov wrote his fairy tale in verse as a student. He actually put pen to paper after reading Alexander Pushkin’s famous fairy tales. The author of ‘Eugene Onegin’, in turn, read ‘The Little Humpbacked Horse’ and acknowledged Ershov’s talent as a writer.

‘The Little Humpbacked Horse’ is an encyclopedia of Russian folk characters. It has them all - Ivan the Fool, the Firebird, the Fish-Kit and the Tsar Maiden – and their crazy adventures are compelling in their total unpredictability. The moral of the story is that you should never judge a person by their appearance. Just like in real life, a fool may turn out to be really smart and the most lousy horse might actually be endowed with magic powers.

When ‘The Little Humpbacked Horse’ saw the light of day, it wasn’t perceived as a children’s story, as it contained elements of social criticism clearly aimed at an adult audience. The first edition of Ershov’s poem was published in 1834 after passing through stringent censorship. The scenes featuring the Russian tsar in a particularly unattractive light were cut out.

In 1843, the fairy tale was banned and was not reprinted for nearly thirteen years. It came out again only after the death of Tsar Nicholas I in 1855.

Schwarts, the inimitable Soviet playwright, wrote one of his most powerful plays during the Great Patriotic War. Although it poses as a fairy-tale, ‘The Dragon’ is a secret, blatant attack against Joseph Stalin, injustice and totalitarianism. The play was first staged in 1943 and was banned right after the premiere.

A brutal dragon terrorizes the inhabitants of a small town who are forced to make sacrifices in the form of the young girls to the monster. It’s Elsa’s turn to be eaten, without a word of protest from the complacent local residents, for that’s the way it has been over the past four hundred years. And yet, one person disagrees. The fearless Lancelot has a sense of justice and is determined to kill the Dragon. This fast-paced play comes with a strong message: always fight against the evil monsters!

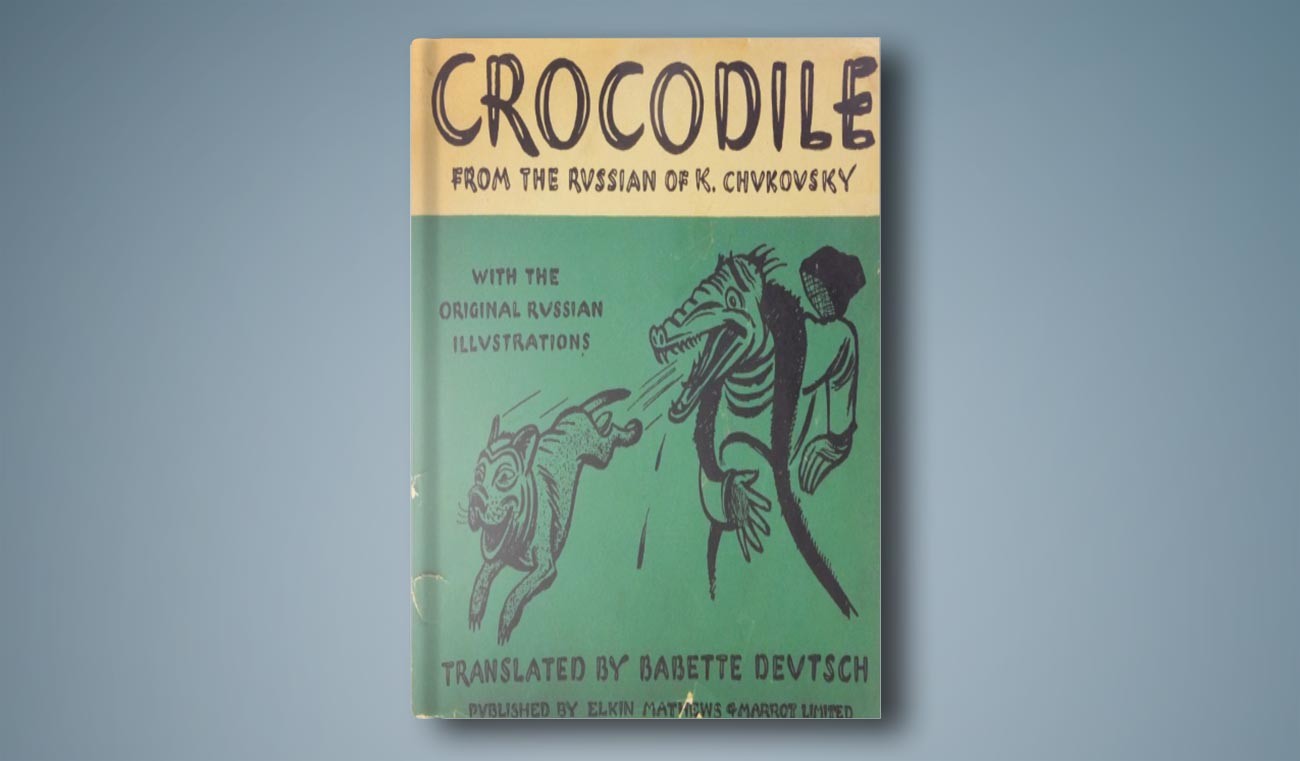

This is one of Chukovsky’s most famous tales that repeatedly came under fire. ‘The Crocodile’ first appeared in book format back in 1919, shortly after the Bolshevik Revolution. And this seemingly innocent children’s story brought with it a storm of criticism.

A reckless crocodile strolls along Petrograd’s (now St. Petersburg) main street, Nevsky Prospect, attacking poor passersby (a policeman and a dog among them). The reptile gets off scot-free until one fearless boy armed with a toy sword, the “valiant Vanya Vasilchikov”, brings the beast to justice. The story also features a girl named Lyalechka, who gets kidnapped by a gorilla from the zoo. No one is there to rescue the poor little girl. But again, Vanya Vasilchikov arrives like a superhero with his pistol.

“He’s a winner! He is a hero!

He again saved his native land.”

In 1919, the tale was a great success and was reprinted several times. However, in the mid-1920s, Soviet censors began to find faults with the story. And in 1926, the book was banned from publication. “What does all this nonsense mean? What political meaning does it have?” Vladimir Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Krupskaya once wrote. “It may be customary to teach a child to talk and read all sorts of nonsense in bourgeois families, but this has nothing to do with the upbringing that we want to give to our younger generation.”

READ MORE: Great Russian writers who didn’t do so well at school

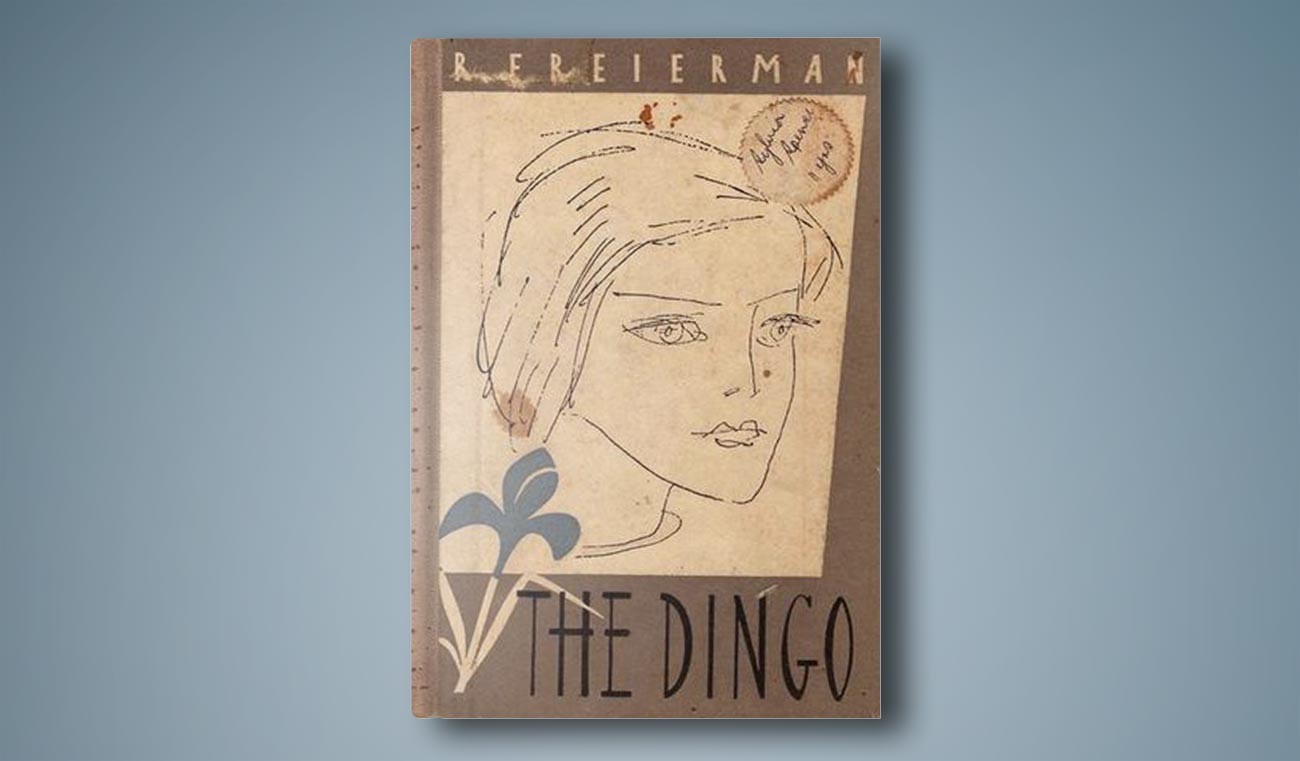

This is probably the deepest, purest and most amazing tale of first love in Soviet literature.

The novel captures the fragile spirit of childhood and adolescence. It’s that rare case when children’s problems are no longer trivial. They are serious and real.

In 1938, Fraerman, the author of stories about the Civil War and a novel about collectivization, decided to write a book about teenage love. Fifteen-year-old Tanya lives in a Far Eastern village where she is friends with a local boy named Filya. Her peace is disturbed by the arrival of her father, who has long abandoned Tanya and has a new family. Torn between anger and love, the teenage girl will have a long way to go before she reconciles with the real world and forgives her father.

This book teaches both adults and children about empathy and acceptance. Critics gave Fraerman’s book a cold welcome, accusing both Tanya and the author of the book of burying themselves in their “exquisite and sublime experiences”, while failing to notice the real, Soviet movement of the “great interesting life” around them.

READ MORE: Top 9 Soviet children’s classics that are still popular today

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox