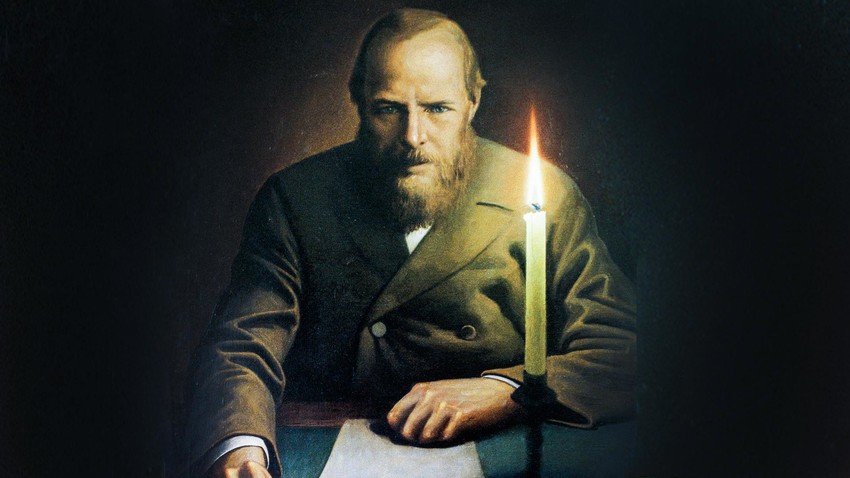

Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky, by Konstantin Vasilyev.

Yuri Prostyakov/SputnikDostoevsky’s novels redeem reality and redefine life. Take any of them to a desert island and don’t worry, you’ll have enough food for thought for years to come (or at least for as long as you stay alive!). With intensity and clairvoyance worthy of William Shakespeare and Sigmund Freud, Dostoevsky penetrated into the darkest corners of moral decay, poverty and human breakdown. Dostoevsky has no peer when it comes to the portrayal of Russian hell. He was an unrelenting exposer of moral corruption, immaturity and hypocrisy.

READ MORE: 5 VILLAINS in Russian literature

The main character in ‘Crime and Punishment’ is a new type of person, possessed by nihilistic ideas.

Vladimir Koshevoi stars as Rodion Raskolnikov.

Dmitry Svetozarov/The ASDS Film Studio, 2007Rodion Raskolnikov is a morally ambiguous young man, who allows himself to shed “blood according to conscience”. “Am I a trembling creature or have I the right,” he unceremoniously asks himself, trying to figure out whether he is “a louse, like everyone else, or a human being?” It’s a done deal when the 23-year-old murders an old pawnbroker lady with an axe, for the sake of a moral experiment. In retrospect, his crime proves to be worse than the creepiest nightmare.

Dostoevsky never sought to be a crowd pleaser. He was a true original who pushed the boundaries of the genre, and of human expectation and ambition, too. ‘Crime and Punishment’ is Dostoevsky’s most perfect crime novel with a psychological twist. We know from the very beginning who killed whom, where, when, why - and even how. And yet, the million-dollar question is what are the existential consequences of the crime and how to live with it. Dostoevsky is convinced that without weaving one’s way through temptation and terrible hardships, without running against moral absolutes, it’s impossible to repent. A man, according to Dostoevsky, is not someone endowed with reason and logic, but one who deliberately goes off the deep end. The writer cherished hope that Raskolnikov can expiate his sin. “Be the sun and all will see you. The sun has before all to be the sun,” Porfiry Petrovich says encouragingly. Per Dostoevsky, forgiveness is possible through suffering.

No one has ever mastered the art of posing questions of right and wrong better than Dostoevsky. But those “accursed questions” are the ones that break the ice, really. “What is hell? I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love,” Dostoevsky stated in ‘The Brothers Karamazov’, his last unsettling novel with the who-done-it-plot. It’s about faith, freedom and family.

Pavel Derevyanko, Sergei Gorobchenko, Aleksandr Golubev, Anatoly Bely and Sergei Koltakov in 'The Brothers Karamazov'.

Yuri Moroz/Colibri Studio production, Central Partnership, 2009Dostoevsky scrutinizes the soul of each character, be it the terrible Fyodor Karamazov or the emotionally unstable Mitya Karamazov, painting quite a grim portrait of the Russian national character. Why do Dostoevsky’s characters undergo groundbreaking metaphysical transformations only when they find themselves in extreme conditions, between life and death, in a moral free-fall? Perhaps, because only at this defining moment do they finally look at themselves honestly for the first time only to produce a scream of despair.

The trailblazing writer possessed a truly forensic mind and used his characters’ “basic instincts” and weaknesses to explain the metaphysical nature of the world. In ‘The Brothers Karamazov’, a beautifully written novel with a splendid detective plot, Dostoevsky explores the ethic facets of one dysfunctional Russian family. Franz Kafka, a fan of ‘The Brothers Karamazov’, called Dostoevsky his “blood relative” and not for no reason. Despite being 100-percent Russian, Dostoevsky’s characters are universal in that they are full of angst, malignity and misery and are determined to go through emotional hell in their unstoppable quest for moral freedom and faith. It’s a shame that Dostoevsky died having written only the first (and smaller) part of ‘The Brothers Karamazov’ duology.

Dostoevsky’s novels have as much drama as the sky brewing an inevitable storm. So, don’t expect Hollywood happy endings. The most vulnerable people of society are the ones that fascinate Dostoevsky the most. He gives a voice to the poor, the sick and the outcast. In ‘The Idiot’, the writer explores love and pity, pride and vileness, generosity and kindness. “Compassion is the most important and, perhaps, the only law of existence for all mankind,” Dostoevsky stated in the novel.

Evgeny Mironov as Prince Lev Myshkin.

Vladimir Bortko/Теlefilm, 2003Prince Lev Nikolaevich Myshkin, the main protagonist, is a man without a future, an epileptic do-gooder who is too kind, naive and ridiculously childish to survive in Imperial Russia. Like the young gazelle is food for a predator, Prince Myshkin is “an idiot” doomed in a world that belongs to daredevil power players like Parfyon Rogozhin.

As Dostoevsky himself pointed out, none other than Jesus Christ and Don Quixote “inspired” the writer to create his Prince Myshkin. Dostoevsky definitely knew how to pick his role models. Some autobiographical traits are also associated with the image of Prince Myshkin, one of the author's most beloved characters, who even “inherited” epilepsy from Dostoevsky. Apart from that, when Lev Nikolaevich starts a conversation about the death penalty in Europe and Russia, he thoroughly describes the feelings of a person facing execution. Interestingly enough, that’s what Dostoevsky himself had experienced! In 1849, the writer was arrested for his involvement with the Petrashevsky Circle, a group of radical St. Petersburg intellectuals who criticized the socio-political system of the Russian Empire and discussed ways to change it. In 1850, 28-year-old Dostoyevsky (who, by that time, had already published two novels, ‘Poor People’ and ‘The Double’) was sentenced to death along with 20 other members of the youth movement. In a strange twist of fate, the sentence was commuted at the very last minute. The mitigation of punishment came as a massive shock and became a life-long memory that Dostoevsky would never forget.

In ‘Demons’ - a powerful novel about the devilish temptation to revamp the world, about demonic possession by the forces of evil and destruction - Dostoevsky predicted the spread of nihilism, chaos and hatred.

Anton Shagin as Pyotr Verkhovensky in 'Demons'.

Vladimir Khotinenko/Nonstop Production, 2014The writer, who had spent four years of hard labor in a Siberian prison, showed himself as a believer and a prophet, too. “Each member of the society checks and reports on one another... Everyone belongs to everyone and everything to everyone. All are slaves and are equal in their slavery. In extreme cases, slander and murder and, most importantly, equality,” Dostoevsky predicted in ‘Demons’. “Only the necessary is necessary - henceforth that is the motto of the whole world… Slaves must have rulers. Complete obedience, complete impersonality,” he wrote. Dostoevsky was a deeply religious man, an Orthodox Christian, who invoked God’s name in his works as often as others mention the weather. “I already need God, because this is the only being that can be loved forever,” Dostoevsky stated in ‘Demons’. The image of a “charming demon” was created by Dostoevsky with incomprehensible artistry. Nikolai Stavrogin has an exceptional mind and a bruised soul. He is an anti-hero, a man with a thousand faces, a psychopath, a manipulator and a serial womanizer. Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev considered Stavrogin the “most mysterious” fictional character in world literature.

READ MORE: 5 books Dostoevsky considered masterpieces

In 1863, Dostoevsky wrote what appeared to be the first existentialist novel, ‘Notes from Underground’, whose narrator sets his strikingly nervous tone in the opening paragraph. “I am a sick person... I am an evil person. I’m an unattractive person.” The leading Russian philologist of the 20th century, Mikhail Bakhtin, called this dostoevskian manner of discourse “a word with a loophole”. It’s a literary Matryoshka doll, with layers and layers of connotations and meanings contained inside.

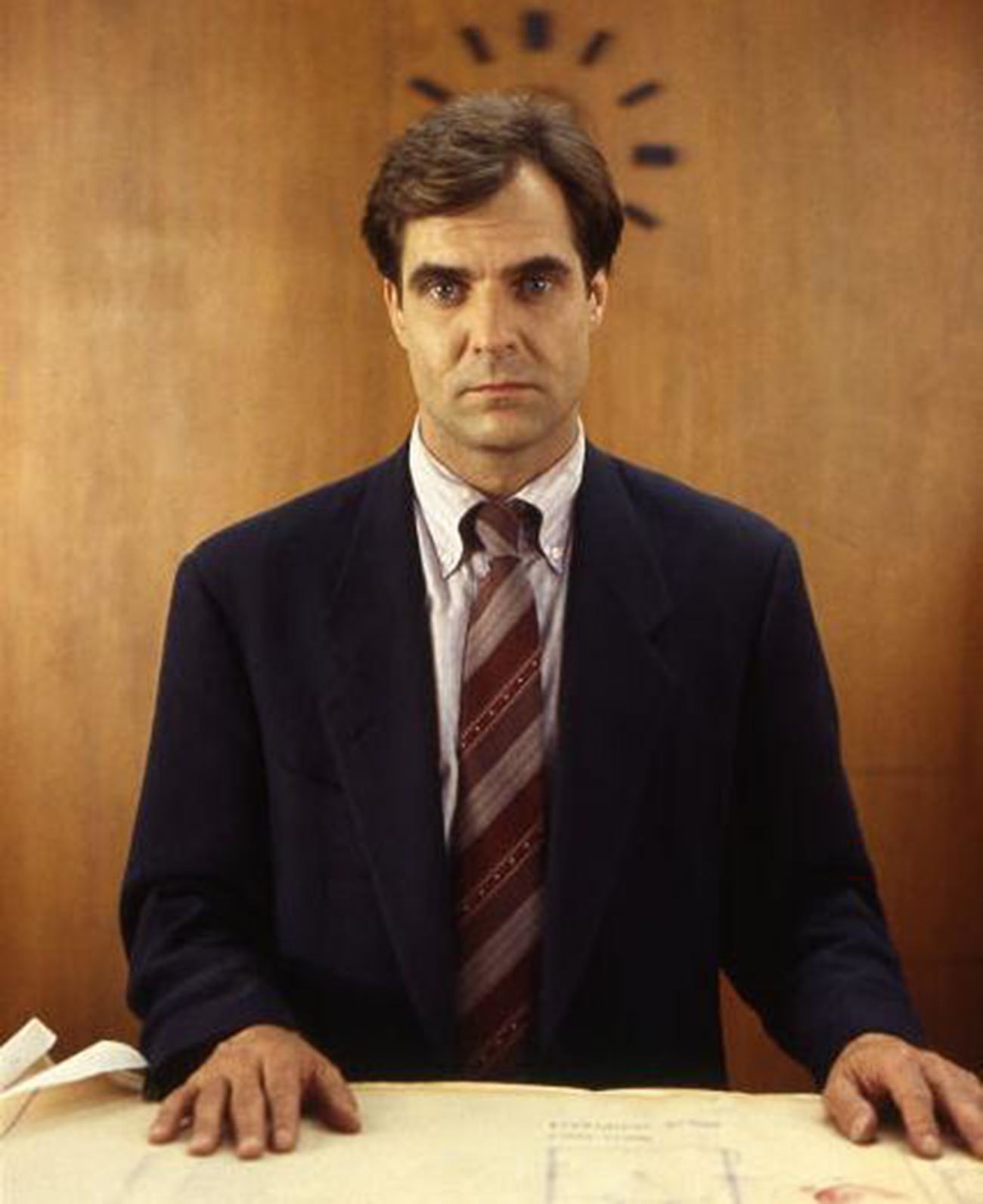

Henry Czerny in 'Notes from Underground'.

Gary Walkow/Renegade Films, Walkow-Gruber Pictures, 1995It’s a confession of a former St. Petersburg official and a philosophical story about the essence of human life; a tragic tale about the nature of our desires and a drama about the sick relationship between reason and inaction. The “underground man”, devoid of a name or surname, argues with his imaginary and real opponents and reflects on the reasons for human actions, progress and civilization. Paranoid, pathological, pathetic, poor, he is a loner most afraid of being discovered. After reading ‘Notes from the Underground’ author of ‘God is dead’ Friedrich Nietzsche had acknowledged that Dostoevsky was the “only psychologist I have anything to learn from”.

READ MORE: 5 reasons why Dostoevsky is SO great

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox